|

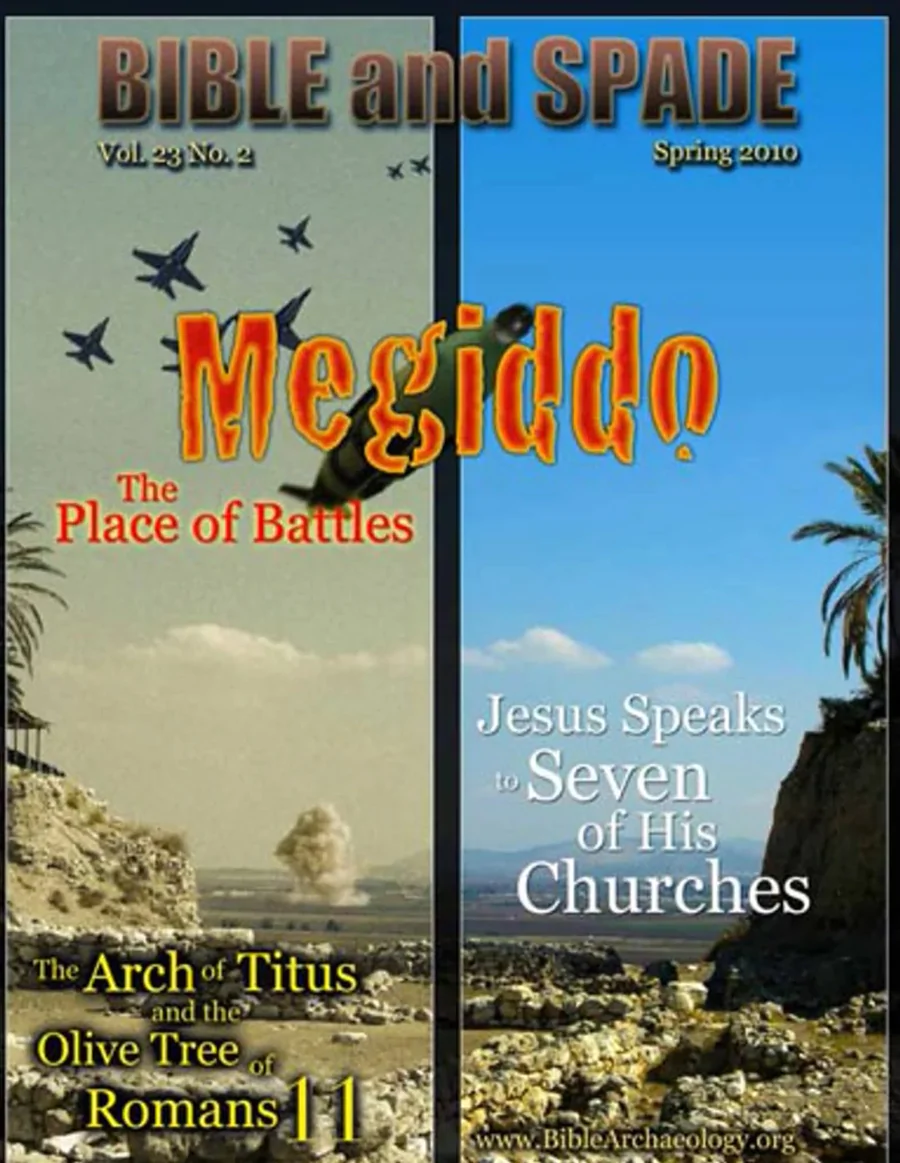

This article was first published in the Spring 2010 issue of Bible and Spade. |

Although Megiddo has been extensively chronicled in extra-biblical sources, it is only mentioned 12 times in the OT1 and once, indirectly, as Armageddon, in the NT (Rv 16:16). Most Christians know that the book of Revelation prophesies an end-times battle that will be fought at a place called Armageddon (Rv 16:16), and many know that “Armageddon” is, in fact, a corruption of the Greek word Ἁρμαγεδών (Harmagedon), or “the hill of Megiddo.” A 35-acre (14-hectare) mound, 200 ft (60 m) high, in northwest Israel called Tell el-Mutesellim is believed to be the site of Megiddo.

The Megiddo Early Bronze sacrificial altar. Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

The Megiddo Early Bronze sacrificial altar. Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

Many Christians travel to Megiddo and walk to the 15-acre (6-hectare) summit because of its eschatological significance. There they look at the excavated buildings, walls, water, and gate system and then move to the north edge of the mound, where they have a magnificent view of the valley—or, more correctly, plain—that spreads out before them and is known as the “Jezreel” in the OT and “Esdraelon” in NT times (Esdraelon being the Greek modification of Jezreel). The plain separates the Galilean hills in the north from Mount Carmel and Mount Gilboa to the south. The immensity of the plain is so astonishing that when Napoleon Bonaparte first viewed it, he was reported to have said, “All the armies of the world could maneuver their forces on this vast plain. . . . There is no place in the whole world more suited for war than this. . . . [It is] the most natural battleground of the whole earth” (Cline 2002: 142; ellipses and brackets original).

The entrance to the Wadi ‘Ara, a narrow north-south pass through the Carmel mountain ridge, is 1.2 mi (2 km) southeast of Megiddo. The south end of the Wadi ‘Ara exits onto the Plain of Sharon and the Mediterranean coast; the north opens to the Jezreel Plain. The international highway traversed this pass and carried traders and armies from Asia, Europe, and Africa. Megiddo’s strategic importance lay in one’s ability to use its nearby hill to monitor such traffic.

In addition to its strategic location, Megiddo had access to the agriculture products from the rich soils of the Jezreel Plain. The Hebrew translation of Jezreel, “God sows,” illustrates the land’s fertility. When George Adam Smith, a late 19th-century-AD traveler, stood on Mount Gilboa and surveyed the Jezreel Plain, he wrote,

The valley was green with bush and dotted by white villages...But the rest of the plain [as] a great expanse of loam, red and black, which in a more peaceful land would be one sea of waving wheat with island villages; but has mostly been what its modern name implies, a free, wild prairie... (1966: 253)

And when the American scholar and explorer Edward Robinson visited the area in 1852, he wrote,

The prospect [view] from the Tell [i.e. Tell el-Mutesellim] is a noble one; embracing the whole of the glorious plain; than which there is not a richer upon earth. . . . A city situated either on the Tell or on the ridge [Mt. Carmel] behind it, would naturally give its name to the adjacent plain and waters; as we know was the case with Megiddo and Legio. The Tell would indeed present a splendid site for a city. (as quoted in Davies 1986: 4; ellipses original)

Megiddo’s mound has a copious spring emanating from a small cave near its base that provided water for those who settled there. Aharoni, in his comprehensive historical geography of the Holy Land, lists four criteria for occupation: strategic location, access to roads, water and agricultural lands (Aharoni 1979: 106–107). Meggido’s location met all four.2

Jezreel Plain from Megiddo. Sprawling on the ridge in the distance is the modern city of Nazareth. In the distance on the right side of the photo is the high round mound of Mt. Tabor near where Deborah defeated Sisera (Jgs 4–5). Photo credit: David Bivin / BiblePlaces.com

Jezreel Plain from Megiddo. Sprawling on the ridge in the distance is the modern city of Nazareth. In the distance on the right side of the photo is the high round mound of Mt. Tabor near where Deborah defeated Sisera (Jgs 4–5). Photo credit: David Bivin / BiblePlaces.com

Entrance to the Megiddo Pass from the northeast. In the upper part of the photo the road begins to weave its way through the hills into Wadi ‘Ara and on south toward the Mediterranean plain. The modern road follows the ancient route of the international highway through Mt. Carmel. Megiddo is 1.2 mi (2 km) to the right (N) of where the road enters the hills. The world’s earliest recorded battle occurred here between Syrian princes and Pharaoh Thutmosis III (ca. 1469 BC). Judah’s king Josiah was fatally wounded when he confronted another pharaoh, Neco II, near here ca. 609 BC (2 Kgs 23:29; 2 Chr 35:20–24). Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

Entrance to the Megiddo Pass from the northeast. In the upper part of the photo the road begins to weave its way through the hills into Wadi ‘Ara and on south toward the Mediterranean plain. The modern road follows the ancient route of the international highway through Mt. Carmel. Megiddo is 1.2 mi (2 km) to the right (N) of where the road enters the hills. The world’s earliest recorded battle occurred here between Syrian princes and Pharaoh Thutmosis III (ca. 1469 BC). Judah’s king Josiah was fatally wounded when he confronted another pharaoh, Neco II, near here ca. 609 BC (2 Kgs 23:29; 2 Chr 35:20–24). Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

The downside for being such an attractive site was the probability of war as nations sought to control this place for their own ends. Like bears drawn to honey, realms fought at and near Megiddo to obtain the fruit of the Jezreel Plain, to control and tax international traffic, or to secure lines of communication to and from far-flung lands. In his historical review of Megiddo and its surrounds, Eric Cline counts no fewer than 34 wars there from ca. 2350 BC to AD 2000 and adds, “Nearly every invading force [of Israel] has fought a battle in the Jezreel Valley” (2002: 11). Proof of this can be seen in some of the 20 occupational levels dating from the Chalcolithic to Persian periods (ca. 5000–332 BC), with evidence that they met their ends in fiery destruction (DeVries 1997: 215).

[Megiddo] was easily accessible to traders and migrants from all directions; but at the same time it could, if powerful enough, control access by means of these routes and so direct the course of both trade and war. It is not surprising therefore that it was at most periods of antiquity one of the wealthiest cities of Palestine, or that it was a prize often fought over and when secured strongly defended. (Davies 1986: 10)

Excavations

The first deliberate archaeological excavations at Tell el-Mutesellim were in 1903–1905, by G. Schumacher on behalf of the German Society for Oriental Research. He had a north-south trench dug the length of the mound that exposed several Iron Age (ca. 1200–600 BC) buildings, and he made soundings along the walls at other places on the site (Aharoni 1993: 1004–1005). Among his finds was a royal official’s seal from the reign of Jeroboam II (ca. 793–753 BC; 2 Kgs 14:23–25). The seal, made of jasper with the image of a crouching lion, had an inscription, “(belonging) to Shema’ Servant of Jeroboam,” the only reference to Jeroboam II outside of the Bible. Unfortunately, the seal has disappeared and only a copy exists (Wood 2000: 119).

Excavations were renewed in 1925 by the Oriental Institute of Chicago at the encouragement of Egyptologist James Henry Breasted and financially underwritten by John D. Rockefeller Jr. This work continued until 1939, when it was interrupted by the onset of World War II. The goal of the first field director, Clarence Fisher, was to clear the mound layer by layer. After four years it became obvious the effort could not be sustained on such a grand scale, and the scope became more limited. For those who are familiar with archaeological techniques used today, it may be of interest that H.G. Guy, who replaced Fisher in 1927, was the first to “use ‘locus numbers’ to designate rooms and or other small areas and the taking of aerial photographs of major structures by means of a camera attached to a captive balloon” (Davies 1986: 19–20).

Yigael Yadin started work at Megiddo in 1960 on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, with additional seasons in 1961, 1966, 1967, and 1971. Yadin helped to clarify the dating of many buildings uncovered by previous excavators. Yadin’s colleagues continued excavating until 1974 (Aharoni 1993: 1005). Since 1992, and every other year since, excavations have been done under the direction of Israel Finkelstein, David Ussishkin, and Baruch Halpern, and under the auspices of Tel Aviv University and The Pennsylvania State University. Their work continues to shed light on previously excavated areas as well as performing reconstruction activities to make the site more comprehensible for visitors (Finkelstein, Ussishkin, and Halpern 2008: 1944–1950).

History

The occupation of Megiddo could have begun as early as ca. 5000 BC (Davies 1986: 25). By 2700 BC a large village was there, surrounded by a great wall—the largest and strongest ever built on the mound (Aharoni 1993: 1007). Visible at the bottom of a large archaeological cut is a worship complex from this period, with a 26Z ft (8 m) diameter circular altar, 5 ft (1.5 m) high, with a flight of stairs to its top. This was also the time when Megiddo became the target of the first known recorded military campaign. An Egyptian tomb inscription from the Early Bronze Age described how Weni, a general under Pharaoh Pepi I (ca. 2325–2275 BC), invaded the region and found fortified towns, excellent vineyards, and fine orchards (Aharoni 1979: 135–37). Weni campaigned four more times around Megiddo to put down insurrections, probably local farmers chafing under oppressive Egyptian rule (Hansen 1991: 85).

In succeeding generations Megiddo continued to attract Egyptian interest, and was the site of the world’s earliest battle for which a detailed account exists. Carved on the walls of Karnak in Egypt is a well-preserved description of how Pharaoh Thutmosis III, one of Egypt’s greatest sovereigns and her finest military strategist, fought a coalition of Syrian princes at Megiddo ca. 1469 BC. The Syrians had occupied Megiddo and controlled the pass through the Carmel ridge, the Wadi ‘Ara. Thutmosis moved a large army from Egypt to a place just south of the entrance to the Wadi ‘Ara. Contemplating his next move, Thutmosis consulted his generals, who urged him not to consider the Wadi ‘Ara but to use two other less narrow valleys north and south of the ‘Ara. His staff feared an ambush in the narrow ‘Ara pass. Disregarding their advice, Thutmosis ordered the army through the Wadi ‘Ara. They traversed the pass unmolested and exited onto the Jezreel Plain, surprising the Syrian princes, who had anticipated that the Egyptian army would come through the two other, less dangerous routes. In the ensuing battle the Syrians were able to escape to the safety of Megiddo, where, after a seven-month siege, the city fell.3 After the siege, the amount of agricultural spoils captured by Thutmosis is impressive: “...1,929 cows, 2,000 goats, and 20,500 sheep...[The] of the harvest which is majesty carried off from the Megiddo acres: 207,300 [+ x] sacks of wheat, apart from what was cut as forage by his majesty’s army...” (Pritchard 1958: 181–82). It is estimated the wheat alone measured 450,000 bushels (Pritchard 1958: 182 n.1). Megiddo was a very wealthy and fertile target indeed!

An ivory sphinx, beautifully and intricately carved, shows the work of a skilled artisan and dates to the 12th–13th century BC, during the Judges period. The fine workmanship shows the wealth of those who lived in Megiddo at the time. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

An ivory sphinx, beautifully and intricately carved, shows the work of a skilled artisan and dates to the 12th–13th century BC, during the Judges period. The fine workmanship shows the wealth of those who lived in Megiddo at the time. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Six-chamber gate at Megiddo. Only the three southern chambers remain today of the massive gate, and they can be seen in this photo. The center chamber is filled with rocks but the first and third are open. It is believed that Solomon constructed this gate and built two more like it at Gezer and Hazor (1 Kgs 9:15). Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

Six-chamber gate at Megiddo. Only the three southern chambers remain today of the massive gate, and they can be seen in this photo. The center chamber is filled with rocks but the first and third are open. It is believed that Solomon constructed this gate and built two more like it at Gezer and Hazor (1 Kgs 9:15). Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

Both General Weni and Pharaoh Thutmosis III campaigned before the Israelites entered the Promised Land ca. 1406 BC.4 Although Joshua defeated the king of Megiddo (Jos 12:21), the Bible does not tell us how. Apparently Joshua did not capture the city because Megiddo was still occupied by Canaanites at the time of the Judges (Jgs 1:27). However, during the time of the Conquest (the period covered by Joshua and Judges), Megiddo became the focus of attention for one nearby city-state, Shechem. The Bible implies that the invading Israelites made peace with the king of Shechem (Hansen 2005: 37). The king of Shechem apparently then used his association with the Hebrews as an opportunity to attack some of his neighbors, including Megiddo. This is reported in the Armana tablets found in Egypt in AD 1887. They were written by various rulers from around the Middle East, including leaders of Promised Land city-states to Pharaohs Amenhotep III (ca. 1402–1364) and Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV; ca. 1350–1334).5 Letter EA 252 is from Labayu, the king of Shechem, who shows contempt for Egypt and implies he had become independent of Egyptian rule (Hess 1993). The king of Megiddo wrote in EA 244 that his city had been besieged by Labayu, complained of Egypt’s lack of response, and pleaded for military assistance:

Ever since the archers returned (to Egypt?), Lab’ayu has carried on hostilities against me, and we are not able to pluck the wool, and we are not able to go outside the gate in the presence of Lab’ayu, since he learned that thou hast not given…archers;…but let the king protect his city, lest Lab’ayu seize it.…He [Lab’ayu] seeks to destroy Megiddo. (Pritchard 1958: 263)

Letters EA 287 and EA 288 are from the king of Jerusalem, who requests reinforcements to protect against the Habiru who are attacking cities. He also accuses Labayu, the king of Shechem, of giving land to the Habiru (Pritchard 1958: 270–72). The mention of Habiru in these tablets refers to a migratory people group that was invading the Promised Land at the time of the Conquest. Many conservative Bible scholars believe the Habiru to have been the Israelites.6

Excavations at Megiddo have revealed that the period when the Amarna Letters were written was one of wealth. Many lovely gold artifacts, and a hoard of 382 ivories, show the prosperity of Megiddo’s rulers. Several ivories have hieroglyphic inscriptions that point to Egyptian influence at the site. Other ivories are pieces of a board game or games, women’s cosmetic utensils, and a small box carved from a single piece of ivory (Aharoni 1993: 1011). Following this time, Megiddo suffered a major destruction dated to the time of the Judges (Price 1997: 147).

Megiddo water-system tunnel. The 262 ft (80 m) long tunnel dug under the city walls to a spring in a cave outside of the city walls. Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

Megiddo water-system tunnel. The 262 ft (80 m) long tunnel dug under the city walls to a spring in a cave outside of the city walls. Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

The first mention of Megiddo after the book of Judges is during the reign of Solomon (970–930 BC). The governor he appointed to Megiddo’s district was required to annually supply Solomon’s palace with a month’s worth of provisions (1 Kgs 4:7, 4:12). Although the evidence is weak, it was probably King David who conquered the city, as evidenced by the remains of a violent conflagration over 3 ft (1 m) deep (Shiloh: 1016). If correct, it was David who built a new city, referred to in 1 Kings, over the remains of the previous one.

In succeeding years Megiddo became a major fortified city. At this level excavators revealed the remains of a large gate complex of six chambers, three on each side, with two towers. In an amazing piece of detective work, Yadin proved that Megiddo’s gate complex mirrored those from the same period found at Gezer and Hazor (1975: 193–94). Yadin concluded that Solomon constructed the three city gates, using a shared plan, at the time he built "the wall of Jerusalem and Hazor and Megiddo and Gezer” (1 Kgs 9:15). Of this discovery, Yadin wrote, “As an archaeologist I cannot imagine a greater thrill than working with the Bible in one hand and the spade in the other” (1975: 187).

Many structures from Solomon’s time, as well as that of the gate system, have been uncovered. However, it must be stated that some archaeologists challenge the dating. Among the contested structures are several long, narrow buildings archaeologists have identified as horse stables, while others argue they were barracks or storehouses (Shiloh 1993: 1021). If stables, the structures fit well with what the Bible tells us about Solomon, who built “cities for his chariots" and "cities for his horsemen” (1 Kgs 9:19). A large grain-storage pit, 69 ft (21 m) deep and 69 ft (21 m) wide, was found near the “stables” and could have provided 150 days’ worth of grain for up to 330 horses (Ussishkin 1997: 467). Parts of this level’s city were destroyed by fire, probably by Pharaoh Shishak, who invaded the country shortly after Solomon died ca. 925 BC (1 Kgs 14:25; 2 Chr 12:2).

An aerial view at Megiddo from the east, with Mt. Carmel in the distance. The prophet Elijah confronted the prophets of Baal on Mt. Carmel (1 Kgs 18:21) and later executed them near Megiddo (1 Kgs 18:40). This area is also the region of biblical Armageddon prophesied in Revelation 16:16. Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

An aerial view at Megiddo from the east, with Mt. Carmel in the distance. The prophet Elijah confronted the prophets of Baal on Mt. Carmel (1 Kgs 18:21) and later executed them near Megiddo (1 Kgs 18:40). This area is also the region of biblical Armageddon prophesied in Revelation 16:16. Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

Stables, barracks, or storerooms? Scholars debate the use of tripartite buildings excavated at Megiddo that have rooms similar to these in the photo that have mangers. Many believe the buildings were stables from the time of Solomon, and Megiddo was one of his chariot cities (1 Kgs 9:19). Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

Stables, barracks, or storerooms? Scholars debate the use of tripartite buildings excavated at Megiddo that have rooms similar to these in the photo that have mangers. Many believe the buildings were stables from the time of Solomon, and Megiddo was one of his chariot cities (1 Kgs 9:19). Photo credit: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

Shishak (who is Egyptian pharaoh Sheshonq I, ca. 945–923 BC) left a record of his invasion of Judah and Israel at Karnak in Egypt, and Megiddo is among the places he listed as being conquered. During the 1929 excavations of Megiddo, Clarence Fisher found a fragment from a stele erected by Shishak that commemorated his capture of the city.

One of the most interesting structures to explore at Megiddo is the large water system, probably built during the reigns of the northern kings Omri and Ahab (ca. 880–853 BC) in order to gain protected access to the spring outside the city walls. A square vertical shaft 82 ft (25 m) deep with steps along its side was dug inside the city walls and connected to a 262 ft (80 m) tunnel dug through rock that led to the city’s water source, a spring in a cave 115 ft (35 m) below the surface. The outside approach to the cave was then concealed and blocked (Shiloh 1993: 1023).

A destruction layer in several buildings at Megiddo denotes the arrival of the Assyrians. The city undoubtedly fell to Tiglath-pileser III (745–727 BC) when he invaded the Northern Kingdom as documented in his annals (Pritchard 1958: 193–94) and the Bible (2 Kgs 15:29). However, many structures, including the city walls, water system, and grain-storage pit, continued in use during the Assyrian period. New buildings displayed typical Assyrian architectural features, and they indicate that the city was an administrative or residential center (Ussishkin 1997: 468).

Stratum II represents the period ca. 650–600 BC, during which the city fell rapidly into decline. Although many of the Assyrian buildings continued to be used, the city was unfortified except for a structure that may have been a fortress. It is unclear who controlled the city, the Israelites or the Egyptians; it was a time when a power vacuum existed in northern Palestine, and both the king of Judah, Josiah (640–609 BC), and the Egyptians saw this as an opportunity to expand their empires. The two kingdoms clashed at Megiddo in 609 BC when Pharaoh Neco II, on his way to assist his Assyrian allies in a battle against the Babylonians, met Josiah. Under circumstances that are not certain, the Bible reports that "Josiah marched out to meet him [Neco] in battle, but Necho faced him and killed him at Megiddo” (2 Kgs 23:29b; NIV). Second Chronicles 35:20–24 describes the same event, adding details that Josiah was wounded in battle on the plain of Megiddo and taken to Jerusalem, where he died. Josiah’s death opened the door for Babylon’s invasion, and Megiddo soon fell into disuse. It was abandoned by the time Alexander the Great conquered the region, ca. 332 BC.

Remarkably, visitors today see acres of ruins, a fascinating water system, and complex gate systems, and they would find it hard to believe that the exact location of Megiddo was lost in history. But, from about 330 BC onward, Tell el-Mutesellim was forgotten as the site of the city of Megiddo. By the fourth century AD, Jerome had only a vague idea of where Megiddo had been, and scholars in subsequent centuries conjectured it was at various other places in the area. When Edward Robinson visited Tell el-Mutesellim in 1852 he wrote that the tell had “no trace, of any kind to show that a city ever stood there” (Davies 1986: 4). It was not until Tell el-Mutesellim was excavated in the early 20th century that the location of the ancient city of Megiddo was known.

The Final Battle7

As fascinating as the history and archaeology of Megiddo may be, the Bible informs us of an even more remarkable happening at or near Megiddo. There, “the kings of the whole world” will be gathered “for the battle on the great day of God Almighty” (Rv 16:14; NIV). The battle will bring an end to the adversary (Rv 16:17), and “Babylon the great” will finally fall (Rv 16:19), reversing the failure of Josiah that had earlier brought Babylon into the Promised Land.8

This final conflict will occur in association with the “mountain” of Megiddo (Rv 16:16), which could imply the ridge of Mount Carmel that rises above Megiddo. During the days of Elijah the prophet, King Ahab (874–853 BC) and Queen Jezebel encouraged and sponsored Baal worship in Israel. This led Elijah to call for a contest to determine who deserved the title of God (1 Kgs 18:21). Both Elijah and the 400 prophets of Baal made altars for their sacrifices. Whichever sacrifice was divinely ignited would prove to represent the true God. Following the total failure of Baal and the dramatic ignition provided by the LORD, Elijah commanded that the prophets of Baal be seized and executed in the Jezreel Plain (1 Kgs 18:40). The LORD’s dramatic victory casts the hope and promise about the coming battle at Armageddon. Just as Baal and his prophets met their end near Megiddo, so Satan and his forces will meet their end at the mountain of Megiddo.

Throughout much of His earthly life, Jesus walked by or gazed down on “Armageddon,” the battleground of history. We can now join Him in looking to this same place in expectation of the day when He will rise to win the final victory over the adversary.

Notes

1 Jos 12:21, 17:11; Jgs 1:27, 5:19; 1 Kgs 4:12, 9:15; 2 Kgs 9:27, 23:29, 23:30; 1 Chr 7:29; 2 Chr 35:22; Zec 12:11.

2 For an elaboration on Aharoni’s four criteria and how they apply to Megiddo, see Hansen 1991: 84–93.

3 For more detailed descriptions of this battle, see Hansen 1991: 86–87 and Cline 2002: 17–22. For an analysis of Thutmosis III’s military prowess, and the possibility that he became pharaoh shortly after Moses killed an Egyptian and fled to Midian (Ex 2:11–15), see Hansen 2003: 16–19.

4 This article assumes the date for the Exodus as 1446 BC and that the crossing of the Jordan (Jos 3) was in 1406 BC. This is derived from a literal reading of 1 Kings 6:1 and an understanding of the beginning of Solomon’s reign as ca. 930 BC. For an in-depth treatment of this issue, see Hansen 2003: 14–20 and Young 2008: 109–23.

5 Most of the correspondence is diplomatic and include letters to and/or from Babylon (13), Assyria (2), Mitanni (13), Alashia (= Cyprus?) (8), and the Hittites (1). About 80 percent of the whole collection consists of letters to and from the rulers of city-states in Canaan (Pfeiffer 1963: 13).

6 For a discussion of the Amarna tablets and the identity of the Habiru, see Archer 1994: 288–95; Wood 1995 and 2003: 269–71.

7 This section is a summary of the last chapter in A Visual Guide to Bible Events, Martin, Beck, and Hansen 2009: 258–59.

8 Whether one views this battle as literally occurring within the Jezreel Plain or believes that the Jezreel Plain is symbolic of the battle location, these insights apply.

Bibliography

Aharoni, Yohanan. 1993. Megiddo. Pp. 1003–1012 in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land 31997 The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography, 2d ed. Philadelphia: Westminster.

Cline, Eric H. 2002. The Battles of Armageddon: Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley from the Bronze Age to the Nuclear Age. Ann Arbor MI: University of Michigan.

Davies, Graham I. 1986. Megiddo. Grand Rapids MI: Eerdmans.

DeVries, LaMoine F. 1997. Megiddo: City of Many Battles. Pp. 215–23 in Cities of the Biblical World. Peabody MA: Hendrickson.

Finkelstein, Israel; Ussishkin, David; and Halpern, Baruch. 1993. Megiddo. Pp. 1944–1955 in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land 5: Supplementary Volume, ed. Ephraim Stern. Washington DC: Biblical Archaeology Society.

Hansen, David G. 1991. The Case of Meggido [sic]. Archaeology and Biblical Research 4:84–93.

———. 1996. The Bible and the Study of Military Affairs. Bible and Spade 9: 114–25.

———. 2003. Moses and Hatshepsut. Bible and Spade 16: 14–20.

———. 2005. Shechem: Its Archaeological and Contextual Significance. Bible and Spade 18: 33–43.

Hess, Richard S. 1993. Smitten Ant Bites Back: Rhetorical Forms in the Amarna Correspondence from Shechem. Pp. 95–111 in Verses in Ancient Near Eastern Prose, eds. Johannes C. deMoor and Wilfred G.E. Watson. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 42. Kevelaer, Germany: Butzon & Bercker.

Hoerth, Alfred J. 1998. Archaeology and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids MI: Baker.

Hoffmeier, James K. 2008. The Archaeology of the Bible. Oxford England: Lion Hudson.

Martin, James C.; Beck, John A.; and Hansen, David G. 2009. A Visual Guide to Bible Events: Fascinating Insights into Where They Happened and Why. Grand Rapids MI: Baker.

Pfeiffer, Charles F. 1963. Tell El Amarna and the Bible. Grand Rapids MI: Baker.

Price, Randall. 1997. The Stones Cry Out. Eugene OR: Harvest House.

Pritchard, James B., ed. 1958. The Ancient Near East. Vol. 1, An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Shiloh, Yigal. 1993. Megiddo. Pp. 1012–1024 in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land 3, ed. Ephraim Stern. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Ussishkin, David. 1997. Megiddo. Pp. 460–69 in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East 3, ed. Eric C. Meyer. New York: Oxford.

Wood, Bryant G. 1995. Reexamining the Late Bronze Era: An Interview with Bryant Wood by Gordon Govier. Bible and Spade 8: 47–53.

———. 1993. Shishak, King of Egypt. Bible and Spade 9: 29–32.

———. 2002. Jeroboam II, King of Israel, and Uzziah, King of Judah” in Bible and Spade 13:4 (2000) pp. 119–20.

———. 2003. From Ramesses to Shiloh: Archaeological Discoveries Bearing on the Exodus–Judges Period. Pp. 256–82 in Giving the Sense: Understanding and Using Old Testament Historical Texts, David M. Howard, Jr., and Michael A. Grisanti. Grand Rapids MI: Kregel

Yadin, Yigael. 1975. Hazor: The Rediscovery of a Great Citadel of the Bible. New York: Random House.

Young, Rodger C. 2008. Evidence for Inerrancy from a Second Unexpected Source: The Jubilee and Sabbatical Cycles. Bible and Spade 21: 109–22.