At the core of the issues regarding the decisions to terminate life, whether in the unborn or terminally diagnosed, is the issue of 'personhood'. The decisions are often troubling and the overall issue has generated much confusion for caregivers and an array of philosophical positions. A source of this confusion and philosophical debate is the lack of a precise definition of 'personhood'. This lack of precision often leads to conflicting arguments and extreme rhetoric from opposing sides and, thereby, deters meaningful dialogue and practical application.

Introduction

Since the 1970’s, with the advent of Roe v Wade and advanced life support technology, the subject of “personhood” has taken a dominant role in life issues. Two main lines of argument, with many aspects of each, have emerged; the “connection concept”, wherein “personhood” is seen as intrinsically connected to life itself and must have all properties and protections of life attributed to it, and the “separation paradigm”, wherein quantifiable markers are used to define “personhood” and the absence thereof is used to justify the termination of life.

The “connection”, or inclusive, argument is advocated most prominently by the Roman Catholic Church. Article 2270 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church reads;

The Human life must be respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception. From the moment of his existence, a human being must be recognized as having the rights of a person- among which is the inviolable right of every innocent being to life.

In Donum vitae III, the Church writes; “Among such fundamental rights . . . every human being’s right to life and physical integrity from the moment of conception until death”.

This position speaks to the metaphysical aspects of the issue; theories of the underlying causes of the verifiable realities. While it provides a powerful starting point and framework, these arguments do not speak to the physical and cognitive markers of “personhood” to which society looks in the current age.

On the other hand, the “separation” argument looks to cognitive and social markers to define personhood. Arguments through the 1970’s, such as those by Mary Ann Warren, look to neocortical reasoning with markers such as consciousness, self-concept and self-awareness. These markers were subjective and difficult to measure. More recently, Shannon and Kockler have presented powerful arguments against subjective and social markers. They present an argument for “necessary preconditions” for being a person. They look to two “critical biological markers”; individuality and neurological development.

Regarding “individuality”, Shannon and Kockler appeal to the “process of restriction” which “occurs two or three weeks after fertilization” when the cells lose their totipotency. Shannon and Kockler state that before totipotency is lost, “this is a strong argument that this organism is not an individual. Therefore, it is necessary . . . for an entity to be an individual before it can be a person”.(Shannon/Kockler 2009: 76). While the emphasis placed on individuality is a valuable focus, recent research may mitigate the force of the “totipotency” argument. A study by Gage and Muotri looks at the role of retrotransposons, or “jumping genes”, which are segments of DNA that can have a profound influence on the genome of the cells and may account for differences in brain functions in people, even those who are closely related such as identical twins. (Gage/Muotri 2012: 29)

Regarding the “neurological development” argument, Shannon and Kockler appeal to the stages of development of the Central Nervous System (CNS); the major stages of which occur in the third, twelfth, and twentieth weeks. They argue for full integration of the CNS as a necessary presupposition for personhood. While this argument deserves respectful consideration, the construct fails when applied universally. Taken to the logical conclusion, this criterion leads to the conclusion that personhood can be gained and, therefore, lost. While some may find this an acceptable argument regarding the unborn, the argument may not gain acceptance in regard to those who, through unfortunate accidents, have lost the full use of their nervous systems. To put it in concrete terms, for example; did Christopher Reeve or, more recently, Eric LeGrand lose any or all of their “personhood” after their well-documented spinal cord injuries which resulted in a loss of full integration of their nervous systems?

Therefore, we suggest that individuality and neurological development are important, but secondary, aspects of “personhood” and, as the argument of Shannon and Kockler stands, the absence of these aspects should not be used to justify the termination of life.

Overall, each side of the issue of “personhood” has compelling points but lacks universal application and remains distinct from each other. We would suggest the need for a model that “bridges” the metaphysical to the quantifiable. Furthermore, we would contend that a Biblical model, based on Genesis 2:7, would incorporate the foundational elements needed to generate a working construct of “personhood” which may be the beginning of a universally accepted definition of “personhood”.

The Argument From Genesis 2:7

Overall, the argument in Genesis 2:7 begins with physical form, not with the abstract concept of life from which many philosophies that are derived from Greek thought begin. After the physical form is presented, then the aspects of “life” and “personhood” are presented. This reflects the concept that a living human is not an incarnate spirit, as other philosophies would argue, but an animated body. (McKenzie 1966: 506) Therefore, the body plays a significant role in a three-part construct; physical form, life, and personhood.

The Physical Form

The phrase literally reads, “And the Lord God formed the man from the dust of the ground”. Our italics attempts to emphasize that “man” and “ground” are exactly the same root in Hebrew: “adam”. This term can mean “man, human, mankind”, or “ground, land”. The connection between these two sets of connotations has a rich and recurring Biblical tradition.

Regarding the present study, adam must be distinguished from the human male. The term adam, according to C. Westermann, refers to a creature in some relation to its creatureliness. Setting aside any theology, the text is describing an individual part of nature, as its own entity. Westermann continues:

Adam is not the human being in any family, political, everyday, or communal situation: instead adam refers to the human being aside from all of these relationships, as simply human. Above all else, however, God’s special salvific activity, God’s history with his people, does not concern the adam. (Westermann 1997: 1:34).

Therefore, Genesis 2:7 is referring to an individual body, a brute form. This is the basis for individuality, or individuation. In this construct, individuation is depicted as foundational to the more abstract aspects, life and personhood, which are imparted to the physical form. It is the forum, or means, through which life and personhood are manifested.

The Breath of Life

Most Biblical scholars see the basis of this image as a connection to the Divine Spirit, ruach adonai. The phrase literally reads, “breathed into his nostrils the breath of life”. The ruach can be understood as “breath, wind, Spirit”. The basic imagery connected with the term is air in motion. According to J. Payne, the term “comes finally to denote the entire immaterial consciousness of man . . . The ruach is contained with its bodily ‘sheath’. At death the body returns to dust” and the ruach can live on (Payne 1980: 2:836). The original connotations, remnants of which remained throughout semantic history of the term, entailed “dynamic vitality” and was connected to imagery of violent or forceful breathing. The vitality of the person was seen to be resident in the breath (Albertz/Westermann 1997: 3:1208).

McKenzie points out that ruach is the principle of life, which is communicated to man, or the individual form. This image is not to be confused with the concept of “soul”. The ruach is “a foreign element to man... it is never conceived as a personal being" (McKenzie 1966: 840). The ruach fills man and animates him and upon physical death goes back to its origin; according to Biblical theology, God. Possibly, the fullest expression of this theology of the ruach occurs on the Cross. Among his last words, Jesus cries out, “Father into your hands I commend my spirit” (Luke 23:46).

We would suggest that the connection to the Divine Spirit, the YHWH Spirit, illustrates the concept that this is a foreign element to the brute form of man. The highest concentration of occurrences of this term is found in the book of Judges. We see men, called “Charismatic Leaders”, who receive or are endowed with this “Spirit of the Lord”. Generally, the Spirit is said to “come upon” them (Judges 3:10, 11:29), “enveloped” him (Judges 6:33), “drove” him (Judges 13:25), or “rushed upon” him (Judges 14:6, 14:19, 15:14). This type of designation is carried on through the early Monarchy. In each case, we see outward actions being the result of this transient force that seems to augment the ruach that is already contained in their bodies. The key is to understand that this supernatural catalyst to the amazing actions of these men seems to tap into the ruach, the breath of life, which is already present and inspires the men to perform actions “above and beyond the expected and their normal habits and powers”. (McKenzie 1966: 841) Therefore, the Biblical theology of the ruach speaks to a force that is conjoined to the body and not intrinsic to it.

A Living Soul

The physical form which was endowed with the ruach, or breath of life, now becomes a “living soul”. The two words which form this phrase are significant; hayah and nephesh. The concept of life in the OT connotes the “principle of vitality. Its language is concrete rather than abstract, and life is viewed as the fullness of power, the pleasure which accompanies the exercise of vital functions, integration with the world and with one’s society. Loss of these is a diminution of life, and the approach of death.”(McKenzie 1966: 507) The OT saw death as the opposite of life. Life is “the vigor and power of the body and its functions, its capacity for pleasure, which is the fullness of life. . . Death is total and Israel knew of no vital activity which survived it.” (McKenzie 1966: 507)

The term hyh is usually rendered as a term connoting some form of the English, “to be”. This is a rough correspondence as Biblical Hebrew does not have the verb structure of English to denote the modern “to be”. It has a basic meaning of life or existence. However, the term hayah connoted more than “simple existence or identity of a person”. According to S. Amsler, The term hyh, generally, gave “rise to a more fully packed and dynamic statement concerning the being of a person or thing, a being expressed in the entity’s actions or deeds, fate, and behavior toward others.” It signifies “to become, act, happen, behave”. This term encompasses the “characteristics of a thing or person”. (Amsler 1997 : 1:360)

The Hebrew term, nephesh, contains the true nature of personhood in this Biblical model. Often this term is translated as “soul”, but this is a corruption of the Hebrew by later Greek influences. The semantic field and connotations of this term seem to bind it to the physical form, yet keep its nature distinct. J.L. McKenzie points out that nephesh “is distinguished from the flesh, but not precisely as noncarnal in the sense in which spirit [ ruach ] is opposed to the flesh”. It is depicted in parallelism with the flesh, but shares experiences- such as appetites and death- with the flesh. McKenzie, among others, has called the nephesh “a totality with a peculiar stamp”. He continues; “the basic meaning can be best understood, it seems, in those uses where nephesh is translated by self or person, but it is the concrete existing self.(McKenzie 1966: 836-837)

Bruce Waltke supports McKenzie’s depiction. Waltke emphasizes that nephesh refers to “life”, but life which “consists of emotions, passions, drives, appetites. Waltke points to the nature of concrete personal existence, not the abstract notion of life which is contained in hayah.(Waltke 1980: 2:589) Therefore, it is significant that in Genesis 2:7 man is called a “living soul”(nephesh hyh). McKenzie points out that the “constitution of man” is presented in Genesis 2:7. This designation seems to be peculiar to man, as other occurrences are considered later editorial “glosses”, explanations or comments that are inserted into texts, which expand and apply the theological authority of the creation of man to other created beings. Furthermore, McKenzie notes how the “living soul” is distinct from the “breath of life”. (McKenzie 1966: 836)

C. Westermann gives a detailed analysis of the term, nephesh. He agrees with most other linguists that the term is denser and encompasses different properties than the modern image of “soul”. He argues that nephesh” does not mean ‘life’ in the general, the very broad sense in which modern European languages use it. Instead, usage is strictly confined to the limits of life: nephesh is life in contrast to death. Consequently, occurrences of nephesh in this meaning divide naturally into two major categories; one concerns deliverance or preservation, the other threat or destruction of life. According to the holistic OT understanding of the person, the nephesh is not set apart as a distinct aspect of the human.(Westermann 1997:2:754-755)

J. Payne points to the holistic view of the OT as well. He argues that “while the OT generally treats man as a whole, it recognizes his essential dualism. Flesh and spirit combine to form the ‘self’, so that while man may be said to have a ruach he is a nephesh. . . In this regard ruach and nephesh overlap.(Payne 1980 2:836). In other words, they overlap as they are part of human existence and find a commonality in the physical form.

The Bioethical Argument

The author(s) of Genesis present a complex model of existence which speaks to the issues surrounding personhood and the termination of life which are being debated today. If we are going to propose a universally accepted argument, we must factor out any appeal to God. Such appeals would turn a bioethical construct into a profession of faith. Such professions, though powerful, do not stand up well to scientific scrutiny which looks to identify and quantify proposed elements. We must look to the philosophical, or bioethical, construct that is presented and which can be applied to today’s circumstance.

A keynote to bioethical principles and practice is human dignity. The Genesis model speaks directly to the dignity of all aspects of human existence; the physical form, the property of life, and personhood. Such dignity is suggested by McKenzie’s argument above, in that the title “living soul” is a designation that is unique to man. Unlike the Greek-based concepts, the Genesis model begins with the individual form, a physical entity. Also unlike the Greek principles, this form does not entrap or impede the transcendent spirit or life as an incarnated soul. This idea tends to devalue the body. Instead, the Genesis model depicts the physical form as being endowed, animated, or imbued with life. In the ancient world, as it remains, life is metaphysical mystery which defies and eludes quantifiable definition. The legal and scientific spheres can valuate and establish criteria for life. They can describe and diagnose life, but appropriating the essential substance of life is still beyond their reach. However, the legal and scientific along with the theological and philosophical spheres have always attributed dignity, an essential worth or intrinsic value, to life. In the Genesis model, the physical form receives the enigmatic life, thus dignifying the human body. This intrinsic dignity, because of its metaphysical aspects, can not be taken or lost by human or physical means. This dignity remains for the life of the being. Analogously, at the dawn of life when the egg receives the sperm and the zygote is formed, life and is inherent dignity is present until the moment when life is lost. This dignity is not a property which emerges or can be lost, but is part of the essence of human existence.

The physical form is the vessel which is filled with the essence or spirit of life. From this union, the conjoining of flesh and spirit, immaterial and material, metaphysical and physical, emerges the self or personhood. Here is the unique blend of genetic traits that form the human being. This is the “totality with a peculiar stamp”, of which McKenzie writes. Personhood is the singular and particular blend of flesh and spirit that is intrinsically, though not identically, connected to life in the metaphysical or abstract form of ruach and the physical construct of the body. Personhood proceeds from the conjoining of the flesh and spirit and, therefore, must share in their traits, value, and dignity. These aspects of personhood are not subjective, contingent on societal dictates and environmental factors. This could best be termed understood as “manifest personhood”, those aspects which are quantifiable and measurable by medical and societal standards. The “personhood” of the Genesis model is the substance, the foundation, of the human who exists and interacts with others. These are not transient qualities which can be gained or lost, but properties which permeate the human. This is the personhood which co-exists with life within the sheath which is the physical body.

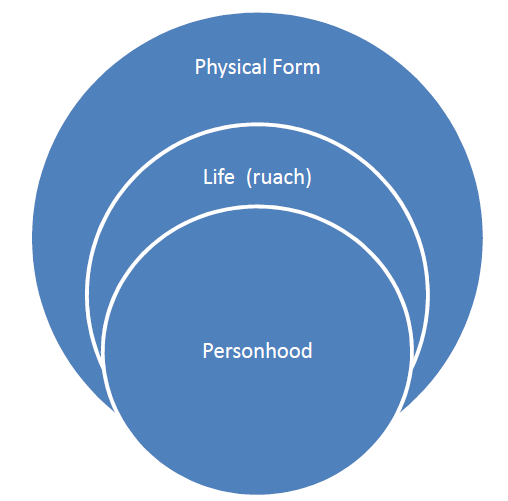

The following diagram attempts to depict this complex relationship:

We begin with the physical aspect of existence. That which is to become a human being is endowed with the metaphysical property “life”. The body contains, or sheaths, this spark of life. From this union, immediately proceeds “personhood”. While it shares the attributes of “life”, personhood extends and manifests itself in society. Those aspects which manifest personhood are the physical traits, cognitive signs, and societal markers that are material and subject to societal valuations. While important on their own, they do not reflect the substantial, or genomic, foundations of personhood or life.

Herein lays the core of the modern debate on the termination of life. Whether in the unborn or in the terminally diagnosed, the question remains the same; do we use the substantial or the manifested societal aspects of personhood to make the decision to terminate life? Or, to put it another way, is personhood, which now stands as the criterion for life-ending decisions in many circles, something that can be gained or lost in the course of one’s life?

The Genesis model would argue against an idea of emergent or lost personhood. It would argue against seeing an unpersonned conceptus or a regressing personhood. The Genesis model sees human existence as having three interconnected parts; the individual physical form, life or Spirit, and Personhood, which immediately proceeds from the conjoining of the other two parts. Personhood, therefore, should be understood as overlapping with life and sharing its attributes, not separated from it. Aristotelian syllogistic logic shows this to be a valid argument.

I → L

P → I

P → L

The major (first) premise states that the Individual was endowed with Life.

The minor (second) premise states that Personhood proceeds from the Individual (who is alive).

The conclusion of the equation states that Personhood (subject of the minor premise) is connected to Life (the predicate of the major premise).

Practically, this means that because personhood shares a connection and attributes with life, it is part of life and must also share in the protections afforded to life in modern society. Based on this connection, proposed by Genesis and validated by Logic, it is unethical to separate personhood from life. Moreover, the “separationists” will use the transient and societal markers as criteria for decisions. In other words, they use only the characteristics and traits which manifest personhood, not the substantial aspects of personhood, to terminate life.

Drs. Clark and Emmett have constructed a strong working definition of physical death that coincides with the Genesis model. Clark and Emmett propose that any definition must entail the metaphysical as well as the physical, or measureable, elements of the loss of life. They argue for the totality of the event and process. Therefore, they propose the following;

Death is the permanent cessation of integrated functioning of a human person, which makes the body incapable of sustaining a living soul. This definition includes both the breakdown of the physical life processes and the separation of the spiritual self from the body. If we exclude the spiritual side of this definition we would reduce the human person to a physical entity (Clark/Emmett 1998: 71).

This definition points to the vital functions and integrated systems of the body. Metaphorically, as we have indicated, the sheath can no longer contain the power of the life therein. This shows the foundational importance of the body to life and personhood.

This definition also brings out the conflict regarding termination of life into bold relief. The definition of Clark and Emmett show the connectedness between physical and metaphysical, or spiritual, life and personhood. Physical death occurs when this connection can no longer occur. When this connection is impossible to sustain, final decisions on termination of life are in order. If these decisions are forestalled and inordinate emphasis is placed on the preservation of the body, the danger of defining life through technology becomes imminent. Life support can become a substitute for life and the patient is artificially suspended between life and death through the pipes and pumps of medical technology.

Those who would separate life from personhood bypass the metaphysical relationship between life, body, and personhood and focus only on the aspects of personhood which extend beyond the self and into society (see diagram). The quantifiable aspects of personhood, those that manifest in human society, are very different than the metaphysical personhood which proceeds from the conjoining of life and body. This is not the substantial personhood; it is the accidental, or particular, personhood that is contingent on societal dictates and environmental factors. Yet, the accidental aspects are often used to justify the termination of life. The Genesis model shows this to be unethical and illogical; one can not defend equating the accidental aspects with the substantial essence. It is not justifiable to weigh scientific or physical markers equally to the metaphysical domain of life. Simply put, the Genesis model, supported by Logic and Christian bioethicists, argues against using physical or societal markers as the criteria for the termination of life.

An illustration of the difference between the manifest physical markers and the underlying metaphysical elements of life and personhood can be found in the Samson narratives (Judges 13-16). Samson’s physical strength and prowess were made manifest in his campaign against the oppressors of Israel, the Philistines. At the base of the tribal stories and theology lies a clear illustration of the Biblical philosophy of life and personhood. Samson’s strength and power were seen as a manifestation of the YHWH Spirit, the supernatural force that connected with the ruach already inside of him. These outward manifestations of prowess were not seen as the metaphysical or spiritual substance of life and personhood. According to Judges 15:18, being thirsty after his epic battle at Ramath-Lehi, Samson called out for water. Water issued from the rock. He drank until his “spirit returned”. There is no indication that this “spirit” is connected to the YHWH Spirit, to which his invincible power was attributed, nor to the breath of life. Although his somewhat insolent request and exhaustion indicates that he felt near death, the “spirit” to which is referred is physical vigor. Physical vigor of this sort can be replenished, as the text illustrates. Physical vitality, connected to life and personhood can not be replenished. At his triumphant death, between the pillars of Dagon (the Philistine god), Samson prays for his nephesh, his particular constitution that is connected to life itself, die with the Philistines (Judges 16: 30). This is not a property that can be replenished. His personal existence will now end. After the temple collapses, his body will no longer be able to contain the blend of life and personhood or to sustain his living soul. In these texts in the Samson narratives we see again how Biblical theology argues against life being connected to simple physical manifestations. Rather, life, and death, is connected to the immaterial or metaphysical properties which are foundational to our existence.

Concluding Proposals

The focus of the debate, justifiably or not, has moved to the manifested aspects of personhood. However, the problem is that no serviceable definition of personhood exists. Yet, all sides of the debate appeal to the concept of personhood. We have to move toward a working and acceptable definition of personhood. Mary Ann Warren tried to arrive at a universally accepted definition decades ago. B. Holly Vautier points out:

There is a sobering interconnection between definitions of death, the meaning of personhood, and the value of human life. For this reason, it is vital that societies continue to endorse a single, uniform definition of death which retains the status of all human beings as persons. Any designation of non-personhood invites revisions in medical and legal standards which lead to the devaluing of human life”. (Vautier 1996 :100).

Also, Shannon and Kockler, leaders in bioethics, point to a confounding issue:

“Yet, another level of complexity comes from the growing accessibility of the fetus. Such accessibility through various monitoring devices such as amniocentesis and fetoscopy, fetal surgery, and the improvements of newborn intensive care units allow caregivers to experience the fetus as a patient. While some would argue that this is nothing new, our capacity to see and aid the fetus directly is a stronger basis for ascribing the status of patient than belief or ideology. The questions can be asked: If the fetus is a patient, might it also be a person? If this patient is not a person, then why treat-other than for the crassest of research motivations? . . .

We are yet to face major dilemmas about personhood of the fetus in light of these new technologies and ways of seeing human life. (Shannon/Kockler 2009 :76-77)

These voices need to be supported. Also, a corollary to Clark and Emmett’s definition needs to be forged that will engage the subject of manifest personhood, that which is quantifiable and validated by society.

Perhaps, a starting point would be looking to the Genome. Genomic manifestation, when upon fertilization one being from two emerges, might be the bridge from the substantial to manifest aspects of personhood. This is when DNA is encoded, meaning the blueprint for all mental and physical traits are established. The genome is established when individual life emerges. It represents the individual physical form, mental capacities, and personality traits. It is an objective standard that is now measurable, due to modern day medical technologies. Moreover, it ties personhood, inextricably, to life. There is no delayed, emergent, or lost personhood with the use of the genome. Yet, the genome guides the manifest personhood. It is not subject to environmental factors, but the environment provides the setting for the genomic traits to play out. This proposal does not underestimate the powerful impact of environment on the development of a human being, but insists on a balance between the importance of the substantial and manifest aspects of existence.

Those who would terminate life on the basis of, only, the manifest aspects of personhood overlook the balance to which the Genesis model points. The Genesis model understands that flesh and Spirit join to produce the undefinable, yet undeniable, spark of life from which personhood proceeds. It understands that personhood, nephesh, is not simply contained in the sheath of the body. However, the construct presented in Genesis 2:7, which recurs through major Biblical texts, does not equate the manifest personhood with the substantial personhood that is entwined with life itself. The groups who would terminate life on the basis of manifest personhood, by logical necessity, split life from personhood. The Genesis model depicts their position to be a false disjunction and, therefore, a flawed argument. Overall, the Genesis model, supported by Clark and Emmett, depicts a powerful three-part interplay between the physical body, life, and personhood. This balanced relationship must be recognized when dealing with questions regarding the termination, and sanctity, of life.

Bibliography

Albertz, R., Westermann, C.

1997 “ רוח”, Theological Lexicon of the Old Testament (3 vols). Peabody: Hendrickson.

Amsler, S.

1997 “העה”, Theological Lexicon of the Old Testament (3 vols). Peabody: Hendrickson.

Clark, D., Emmett, P.

1998 When Someone You Love is Dying. Minneapolis: Bethany House.

Gage, F., Muotri, A.

2012 What Makes Each Brain Unique. Scientific American 3: 26-31.

McKenzie, J.L.

1966 Dictionary of the Bible. Chicago: Bruce.

Payne, J.

1980 “רוח” Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Chicago: Moody.

Shannon, T., Kockler, N.

2009 An Introduction to Bioethics (4th ed). Mahwah: Paulist.

Vautier, B. H.

1996 Dignity and Death: A Christian Appraisal. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Waltke, B.

1980 “נפש” Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (2 vols). Chicago: Moody.

Westermann, C.

1997 “אדם” Theological Lexicon of the Old Testament (3 vols). Peabody: Hendrickson.

Westermann, C.

1997 “נפש” Theological Lexicon of the Old Testament (3 vols). Peabody: Hendrickson.