Traditional liberal scholarship claims that the book of Genesis is a jumble of conflicting, contradictory sources. Genesis 1, they say, was written during the exile in Babylon by priests (ca. 586 BC). Genesis 2 was written sometime around the period of Solomon (ca. 950 BC). Genesis 1 was part of the 'P Document' (Priesty Code) that runs through the whole book in various places. Genesis 2 belongs to the 'J Document,' which also goes through Genesis. It is called J because it prefers the divine name Jahweh (pronounced Yahweh)

This article was first published in the Winter 2010 issue of Bible and Spade.

Commandeering Genesis 2 to Teach the Documentary Hypothesis

Proponents of this theory claim that differences, repetitions and contradictions between various sections of Genesis demand multiple authors from different time periods and beliefs. Genesis 1 and 2 are brought forth as prime examples of two conflicting layers. This article will show how the Paradise story in chapter 2 was manhandled and “water-boarded” into being a star witness in this court of modern scholarship. It will show that Genesis 1 and 2 are not two conflicting creation stories. They are a Creation Story and a separate Garden Story.

Where This Theory is Found and Where It is Not

This viewpoint is not simply hidden away in technical literature. It is found in the notes of modern study Bibles quoted in this article. Books introducing the OT touting this view are sold in secular bookstores. The author of this article met a young man in McDonald's studying it in his Sunday School quarterly. A colleague once told him he had been taught it in his church seminar for Sunday School teachers.

What is often not mentioned is that even liberals themselves are now turning away from it to other viewpoints. It will be seen that many negative critics have become disenchanted with this system for reasons that are displayed in this article. Indeed, the dates of J and P have been flipped around, so that P is now the earliest source1 (Whybray 1989: 231). One liberal scholar goes so far as to call it “frenzied digging into the Bible’s genesis, so senseless as to elicit laughter or tears” (Sternberg 1985: 13).

The author of the introduction to Genesis in the Harper Study Bible, Joel Rosenberg2, emphasizes that he uses the “customary” source divisions but feels “preliterary tradition” is more important (1993: 3–4). He is betraying a more “modern” disenchantment with the Documentary Hypothesis. It is often presented with lip service, and then quickly pushed into the corner in favor of literary analysis techniques. The drill sergeant’s chant is changed to, “We like it! We love it! We want none of it!”

Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918) was a German theologian who held teaching positions at various institutions throughout his career. He was one of the most significant figures in destroying faith in the integrity of the Scriptures with his infamous JEDP hypothesis, which claimed the writings of Moses were really drawn from multiple authors at different times. Although archaeological, historical and biblical studies have shown the JEDP theory to be totally erroneous, many academic institutions, including Christian seminaries and colleges, tenaciously hold to this idea of the development of the Bible and Israelite religion. Author Ferguson’s analysis of Genesis 1–11 provides an avenue of defense against this skepticism. Photo: Public Domain

Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918) was a German theologian who held teaching positions at various institutions throughout his career. He was one of the most significant figures in destroying faith in the integrity of the Scriptures with his infamous JEDP hypothesis, which claimed the writings of Moses were really drawn from multiple authors at different times. Although archaeological, historical and biblical studies have shown the JEDP theory to be totally erroneous, many academic institutions, including Christian seminaries and colleges, tenaciously hold to this idea of the development of the Bible and Israelite religion. Author Ferguson’s analysis of Genesis 1–11 provides an avenue of defense against this skepticism. Photo: Public Domain

Two Different Accounts of Creation?

Advocates of this viewpoint have enthusiastically latched onto these first two chapters, seeing them as an excellent way to introduce their version of the book of Genesis. In order to do this they must make Genesis 1 and 2 into two contradictory, conflicting accounts of creation. One is left with the impression that if Moses couldn’t even get his very first story straight, how can we trust anything else he wrote?

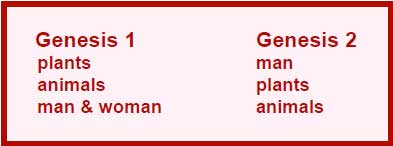

Richard Elliot Friedman, in his book Who Wrote the Bible?, claims that the first chapter of the Bible “tells one version of how the world came to be created, and the second chapter... starts over with a different version of what happened.” He claims that on several points they contradict each other and describe the same events in a different order (Friedman 1987: 50–51). He has the following table to illustrate this:

Friedman claims that this is a parade example of evidence for documents in Genesis. Friedman’s book is sold in secular bookstores to the general public.

Friedman claims that this is a parade example of evidence for documents in Genesis. Friedman’s book is sold in secular bookstores to the general public.

Norman Habel has written a book in the Fortress Press “Guides to OT Scholarship” series called Literary Criticism of the OT. In his chapter “Discovering Literary Sources,” he devotes a good deal of space to comparing Genesis 1 with chapters 2–4. He concludes that the differences in style he tabulates prove two different authors. He goes to great lengths to show that chapter 1 is stiff, formal enumeration, while chapter 2 is free flowing, “folksy” narration (1971: 18–27).

The fact that the Fortress guide series has a second book presenting a totally different view of “literary criticism” shows the confusion that haunts modern negative criticism of the OT. The second book, called The OT and the Literary Critic, claims that looking at Genesis as if it was put together from separate strands is of little value and is a way to avoid interpretation. The author qualifies the words “put together from separate strands” with the skeptical comment, “if indeed it was” (Robertson 1977:6–7)!

The traditional documentary method is not limited to college textbooks. A similar approach is found in the introduction and notes of the Oxford edition of The New English Bible (1970:xxiii, 1f). It is also found embedded in at least two other Bibles (New American Bible 1987: 1–3; Harper Collins Study Bible1993: xx–xxi).

Flaws and Inconsistencies in the Theory that Genesis 1 and 2 are Two Creation Stories

1. Speaking of Two Creation Accounts Disregards the Canonical Shape of Genesis

This observation does not come from a conservative scholar but from the very liberal Introduction to the OT as Scripture by Brevard Childs, OT professor at Yale University. He chastises his colleagues who use Genesis 2 as a contradictory creation story as follows: “By continuing to speak of the ‘two creation accounts of Genesis’ the interpreter disregards the canonical shaping and threatens its role both as literature and as scripture” (1979: 150).

Childs bases his observation on the introduction to the Garden Story. Genesis 2:4 states, “These are the generations (family history, story) of the heaven and the earth.” [Scriptures, unless otherwise specified, are the author’s translation.] This phrase occurs ten times in the book of Genesis: “These are the generations of heaven and earth” (2:4), “of Noah” (6:9), “of Shem” (10:1), “of Shem” (11:10), “of Terah” (11:27), “of Ishmael” (25:12), “of Isaac” (25:19), “of Esau” (36:1), “of Esau” (36:9), and “of Jacob” (37:2). In Genesis 5:1, “the book of the generations of Adam” is roughly the same phrase, making the total eleven.

In every case, the phrase “generations of” refers to events that come after the generation has taken place. For example, what follows the “generation of Isaac” (Gn 25:19) is not the story of Isaac. Chapters 25–35 are all about Jacob, Isaac’s son. In Genesis 2:4, then, it must refer to what happens AFTER creation, and therefore the rest of chapter 2 could not be another creation story. Childs notes that what follows this phrase cannot be another creation story but what follows “proceeds from the creation in the analogy of a son to his father” (Childs 1979:49–50).

Another liberal, John Skinner, in the International Critical Commentary on Genesis, made this observation long before Childs. He states that the phrase “must describe that which is generated by the heaven and earth, not the process by which they themselves are generated.” He considered this fact a “difficulty for the Documentary Theory and described various convolutions liberals went through to resolve it. Some of them felt that 2:4 accidentally got moved out of place and shouldn’t be there to upset their theory about the documents (Skinner 1930: 40–41).

2. Making Genesis 2 a Second Creation Story Disregards What the Story Actually Says!

Genesis 2 is not a creation story; it is a Garden Story with some special acts of creation in it. It is not a story about the whole planet but about a small part of the planet. The Hebrew word for “earth” (‘erets) can often refer to a small piece of ground (Gn 23:12). It is used three times in Exodus 10:12. Once in the verse it refers to the land of Egypt and twice of the farmland that was destroyed by locusts.

The plants referred to in 2:5 and 9 are not the same plants as in Genesis 1:11. They are not like the grass created in chapter 1 that will grow by itself, but are cultivated, domestic plants. The reason they are in the garden is not because God has not created them yet, but because it doesn’t rain there and there is no man to take care of them (2:5, 15).

God did not create a garden, he planted one (2:8). He caused the seed to “sprout up” from the ground (v. 9). The same Hebrew word translated here as “sprout up” (xm;c.y yatsmach) is used in Isaiah 55:10 and Psalm 147:8 to refer to the rain causing plants to come up from the ground. God is not so much a creator here as a farmer.

There is a general description of the creation of man in 1:26. In 2:7 there is a more specific account of the same event. As such some have translated 2:7 so as to read, “The LORD God had (previously) formed man” (Stigers 1976: 65). This translation is not completely necessary, as Genesis 2:7, while not a complete creation story, is an expansion of what happened on the last day of creation.

The animals created in 2:19 are not identical with those of Genesis 1. For example, there are no fish or water animals. They are special acts of creation fitted specifically for Paradise. They have a different physiological makeup. Lions are created to eat straw, as nothing hurts or destroys in God’s mountain (Isa 11:7–9). The snake can talk and has powers of cognitive reasoning. He would have to be a serpent with vocal cords! Eve does not seem shocked by this. Apparently the animals in the garden were considerably different from ordinary animals created on the sixth day.

3. Making Genesis 1 Written by Professional Priests Conflicts with What is Found in This Chapter

The Harper Study Bible describes the author(s) of the P Document as intensely concerned with priestly matters (1993:xx, 3). Notes in the New English Bible introduce Genesis 1 as “the creation account, composed by priests” (1970: 1). Actually, it is more what is not there that is conspicuous by its absence. There is nothing about the origin of sacrifice or cult in Genesis 1. Oddly, the first mention of someone building an altar is Noah in the J Document, allegedly written by an official theologian in Solomon’s court (Gn 8:20)! In this verse the use of the divine name Yahweh marks it as part of the supposed J Document. One would wonder why priests who were “intensely concerned” with their occupation would not work some of their craft back into primeval history.

There is nothing about man keeping the Sabbath. Only God rests on the seventh day. The command is never passed on to Adam, at least in the P and J Documents. Priests writing at the end of the kingdom of Judah would rarely have missed a chance to work the Fourth Commandment into Genesis 2:3. Moreover, nothing is said of any special festival day. The function of lights on the fourth day is more from the perspective of farmers rather than priests.

There is no classification of animals as clean or unclean until the Flood (7:2). Animals in verses 20–25 are classified by size and means of locomotion. This is especially significant when the author of the P Document was supposed to be obsessed with cultic details. At the end of chapter 1 (v. 28), a vegetarian diet is given to mankind. This is not a priestly regimen. According to the laws of sacrifice in Leviticus 6:25f and 7:11–34, eating the meat of certain sacrifices was a fixed worship ritual.

The specification in Genesis 1:29 that all the trees having seeds are for food does not contradict the command in 2:17 forbidding eating of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. In the first place, nothing is said about this tree having seeds. Also, there is no indication this tree had been planted when Genesis 1:29 was spoken.

4. Making Genesis 2 Written by Someone Promoting Davidic Kingship in Jerusalem Conflicts with What is Found in the Paradise Story

According to the notes in the Oxford Edition of the New English Bible, the J Document was perhaps written during the reign of Solomon. Its purpose is to suggest that the kingdom of Israel was the fulfillment of promises made in Genesis to the patriarchs (New English Bible 1970: xxiii). Interestingly, royal language suggesting kingship is only found in the P Document in 1:26–28.

This royal role is, however, given to both male and female. They are to subdue (a kingship word!) nature and rule (kingship!) over it. They are not to rule over each other or other human beings who will be born later. One of the very startling differences between the creation account in the Bible and the literature of the ancient Near East is that kingship is never lowered from heaven by God (Oppenheim 1969: 265). An empire somewhat like the Davidic Empire is not

introduced until 10:8–10, and is not in the line of Shem from which David comes. Moreover, it does not seem to be narrated with a commending tone.

Why would the garden of Eden be sited in the Tigris-Euphrates area, from whence future enemies of Israel would arise (2:10–14)? One would also think Jerusalem would be mentioned. Later Jewish tradition actually did have creation and Eden in Jerusalem, from a rock on the Temple Mount. An ancient painting in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher depicts the blood from Christ dripping down on Adam’s skull at Golgotha.

If this chapter comes from Solomon’s era, why was nothing said about building, which was an integral part of Solomon’s reign? Indeed, one of the prime differences between creation in the Bible and in the ancient Near East literature is that God does not give the brick mold to mankind (Farber 1997: 511–15; Heidel 1951: 62–63, 72). One would also wonder why Adam, unlike Solomon, is not given a harem instead of one wife (1 Kgs 11:3). And why is the gold outside the garden in the land of Havilah (2:10f)? Adam never brings the gold into the garden like Solomon’s ships brought it to Jerusalem (1 Kgs 10:14, 21–22).

Contradictions, Ancient Near Eastern Literature, and the Modern Mindset

Did the Documentary Hypothesis Drown in Noah’s Flood? Could One Person Have Written All of Genesis 1–11?

The startling claims suggested by these above questions do not come from a fanatical fundamentalist tirade against the Documentary Hypothesis. Far more shocking than the questions is their provenance. They come out of the University of California, Berkeley campus (Kikawada and Quinn 1985: 17–21)! Two professors from this school published a study called Before Abraham Was. Isaac Kikawada taught Near Eastern Studies and Arthur Quinn taught Rhetoric.

They aggressively assert that the compulsion to divide Genesis 1–11 into multiple sections derives from ignorance of how ancient Near Eastern literature was crafted and understood. They boldly claim that these chapters could have had only one very gifted and versatile author. To support this they compare the primeval history of the Bible with epics available in literature written before the time of Abraham. One of the epics they find close in outline and style is the Atrahasis Flood story. They claim that repetition was a common trait and need not be evidence of multiple authorship.

This viewpoint is not new. Years ago, British scholar P.J. Wiseman asserted that the charge of repetition could be brought against nearly every piece of ancient writing. Later editions of the book were updated by his son D.J. Wiseman, who was a specialist in Near Eastern studies. Repetition, he claimed, was actually an evidence of the antiquity of the Genesis material. He quotes Arno Poebel, who published Sumerian tablets for the University of Pennsylvania. He stated, “Readers of the Bible, moreover, will recognize the quaint principle of partial repetition or paraphrase” (Wiseman 1958: 103).

Kikawada and Quinn persuasively argue that the first eleven chapters of Genesis are not a literary patchwork by different editors, but are the work of one author of extraordinary subtlety and skill. They warn the reader that when someone thinks they find something wrong with an ancient author, there may actually be something wrong with the readers (Kikawada and Quinn 1985: 9–14 and back cover).

They sagaciously observe that the numerous differences in style, names and vocabulary are so closely intertwined in the Flood story of Genesis 6–9 that they cannot possibly be separated. The “sources” therefore cannot be shown to exist there. The better explanation is that there is one author who uses various modes to fit his liking. They audaciously state, “All the contrasts found earlier between the separate sections are here together in a single story of considerable charm and power. The documentary hypothesis DROWNS in the flood...” (Kikawada and Quinn 1985: 21, emphasis mine).

They claim that an ancient Near Eastern audience with a repetitive mindset would not see all the contradictions that moderns with engineering mentalities seem to find. Some contemporary scholars are jolted by what they think is a double account of creation. When some moderns look at Genesis 1 and 2, they naturally assume two creation stories have been combined. Kikawada and Quinn, however, state, “Yet when we look at ancient Near Eastern stories of human creation, such a double-creation is not unusual. We find it in the Sumerian primeval history of Enki and Ninmah” (Kikawada and Quinn 1985: 39).

Some editors, of course, claim that here, too, two different stories have been combined (Klein 1997: 516). But why would ancient people have put them together, then, if they were so flagrantly contradictory? Perhaps the ancient mind did not think like we do. Samuel Noah Kramer, dean of Sumerian studies, had a different viewpoint. Even though there are two accounts of creation, Kramer sees them as belonging to one author. He states, “In both sections it is quite possible to follow the author’s thinking and reasoning as he invented the scenes and episodes that constitute the plot of the tale.” Though not a fundamentalist Bible scholar, Kramer saw that two very different sections did not mean there are two different authors (Kramer and Maier 1989:13).

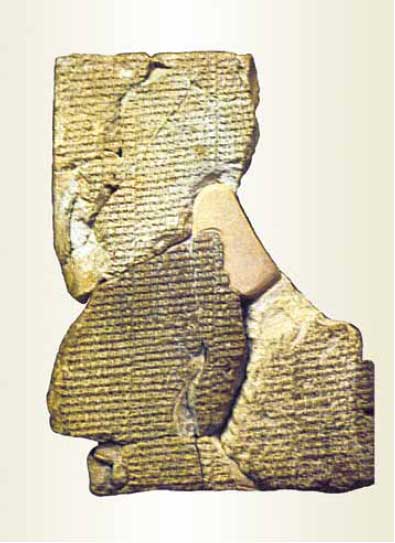

Tablet with the Atrahasis Epic. The Berkeley scholars Kikawada and Quinn cited in this article refer to the Atrahasis Flood story as paralleling the repetitious style of Genesis 1–11. Even non-Christian scholars are finally beginning to acknowledge the subjective and erroneous multiple authorship claims regarding the early chapters of Genesis. Credit: Bryant G. Wood, ABR

Proponents of the Documentary Hypothesis systematically and regularly ignore the significance of the Amarna Letters. These cuneiform-inscribed clay tablets, found at Tell el-Amarna, Egypt, represent correspondence between minor Canaanite kings ruling under Egyptian hegemony during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten. These documents provide unique insights into conditions in Canaan just a few decades after the Conquest and demonstrate the common practice in the ancient Near East of cuneiform tablet writing. Credit: Miichael Luddeni, ABR

What Makes People See Contradictions?

Contradictions are very often in the mind of the beholder. Some moderns see contradictions all over, while the ancients may have seen none. If there are so many contradictions between Genesis 1 and 2, one would wonder why the omnipresent, omniscient later editor did not do a better job of removing them. The author of the introduction to Genesis in the Harper Study Bible claims “these alleged sources are orchestrated so skillfully and meaningfully by a later editor that the...true magic arises not from the sources in their original state—if this can be known—but from their assemblage in a unified whole” (Rosenberg 1993: 3–4, emphasis mine). Perhaps the ghostly editor, if there was one, saw no contradictions because they were not there!

What causes us to see contradictions? It is, generally, from not having all the facts. Kenneth Kantzer, one of the founders of Trinity Seminary in Deerfield, Illinois, tells an account of his aunt’s death found in two different newspapers. One newspaper said his aunt was hit by a car while crossing the street and died later that day. Another paper said she was killed when the car in which she was a passenger collided with another vehicle. Both accounts were true. She was hit by a car while crossing the street. Someone put her in his car to take her to the hospital. On the way there was a collision in which she was killed.3 Not having all the facts can leave us with a misleading feeling that there is a very serious contradiction.

An Alternate Explanation for Differences in Various Parts of Genesis

It can be seen that differences of style in the first two chapters of Genesis can be accounted for by the fact that they are different genres, not necessarily by different authors. Chapter 2 is a Garden Story with some special acts of creation. Chapter 1 is a tabulation of information about creation. They have different purposes, and thus different styles. Genesis 1 is perhaps a hymn that was put into structured form for the sake of memory. Chapter 2 is a family story about important happenings that affected their future.

Data for virtually everyone’s family history comes from two very different sources—clerical material and narrative data. We get a lot of facts from archival documents like birth certificates, property deeds, marriage licenses, family Bibles and obituaries in newspapers. We also get information from anecdotes and stories of aged relatives who personally experienced much of the family history. We may also read narrative reports about family history in newspapers and county histories. The person who tells a very exciting story may be the same one who recorded a list of monotonous statistical data in the family Bible. Differences in style may not always indicate differences in authorship.

P.J. Wiseman had a very intriguing view of how Genesis was put together. He claimed that the eleven phrases “these are the generations of,” were actually notations in a collection of eleven clay tablets which were written by various patriarchs under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit (1958: 45–89). Ancient ancestors like Adam, Shem, Noah, Terah, Isaac and Jacob carefully compiled clerical data and narratives about their family history. This was done under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Abraham may have taken his family records to Canaan, with Jacob later taking them all to Egypt.

In Treasures from Bible Times, Alan Millard describes large houses in Ur, the city Abraham left on his journey toward Canaan (Gn 11:28). He states that some of these homes had small archive rooms containing clay tablets telling about the lives of the occupants of those houses. Some houses had scores of clay tablets with hymns, prayer and legends from distant days. Some of this data would have been very important in transacting business and in the allotment of inheritances (Millard 1985:52–53).

These tablets would have been written in the Babylonian language, using hundreds of cuneiform symbols. As part of the royal family, Moses may well have been trained for the diplomatic service. Stephen said Moses was “educated in all the learning of the Egyptians” (Acts 7:22). Almost four hundred cuneiform clay tablets were discovered in Egypt in the Amarna corpus. They are in the peripheral dialect of the Babylonian language. The tablets are communications from kings in the land of Canaan to the Egyptian pharaoh. They come from around the time of Moses and show that there was lively diplomatic activity in Egypt using Babylonian as the lingua franca for communication with kingdoms in the east (Millard 1985: 65–67).

When the Exodus took place, the Israelites took the bones of Joseph with them (Gn 13:19). Since Joseph’s mummy was preserved, it would not have been unusual if certain important records kept by Joseph were also rescued when a new pharaoh arose who did not recognize Joseph (Ex 1:8). Perhaps these records were included in Joseph’s burial case. Moses may have taken these tablets with him and put them together under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. This scenario, of course, is based on speculation. It would, however, account for the occasional choppiness and differences in style, as well as the abrupt transitions from place to place. This would certainly be more logical than the ideas of certain modern scholars who want to chop Genesis up in a food blender.

What Difference Does All This Make Anyway?

If the creation and Paradise stories are all garbled and contradict each other, then doubt is cast about whether there was a literal Paradise. In some of the seminaries I attended, Genesis 2 and 3 were simply treated as a myth about what we go through as we enter into childhood. The Garden of Eden story, they said, was simply a myth about how we abandon pristine innocence and make wrong choices as we progress into adulthood. If, however, Eden is merely a hazy, nebulous myth, it makes one wonder about heaven. Will Jesus really be able to give us to eat of the tree of life in the midst of the Paradise of God (Rv 2:7)? Is the future Paradise in heaven also a hazy, nebulous mirage? We have seen that given a fair, close, sensible reading, the Garden Story in Genesis 2 fits the tests of a real, consistent, rational narrative. Therefore, we have no reason to think that the heavenly Garden Story is no less reasonable. Trying to make the Garden Story a garbled, confused version of chapter 1 is indeed an attempted hijacking of Paradise!

Notes

1Liberal scholar at Yale, Brevard Childs, states, “Moreover efforts at determining the relative age of the sources must remain extremely provisional” (1979: 148). The author of this article was preparing to teach the Documentary Theory in a liberal college. He was surprised to find in a key chapter like Exodus 14 the famous, top-of-the-line proponents could not agree about what documents were included and precisely where they were embedded in the chapter.

2This author is not to be confused with the Joel Rosenberg who is a Messianic prophecy teacher.

3This anecdote was given in a lecture by Professor Charles Horne at Wheaton College in June of 1966.

Bibliography

Childs, Brevard

1979 Introduction to the Old Testament as Scripture. Philadelphia: Fortress.

Farber, Gertrude

1997 The Song of the Hoe. Pp. 511-13 in The Context of Scripture, vol. 1, Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Friedman, Richard Elliott

1987 Who Wrote the Bible. New York: Summit Books.

Habel, Norman

1971 Literary Criticism of the OT. Philadelphia: Fortress.

Harper Collins Study Bible

1993 New Revised Standard Version annotated by Society of Biblical Literature. San Francisco: Harper Collins.

Heidel, Alexander

1951 The Babylonian Genesis. Chicago: University of Chicago. Kikawada, Isaac M. and Quinn, Arthur

1985 Before Abraham Was. Nashville: Abingdon.

Klein, Jacob

1997 Enki and Ninhah. P. 516 in Context of Scripture, op. cit.

Kramer, Samuel Noah and Maier, John

1989 Myths of Enki, the Crafty God. New York: Oxford University.

Millard, Alan

1985 Treasures from Bible Times. Batavia, IL: Lion Publishing Company.

New American Bible

1986 Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

New English Bible

1970 Oxford Study Edition. New York: Oxford University.

Oppenheim, A. Leo

1969 The Sumerian King List. Pp. 265-66 in Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, ed. James B. Pritchard. Princeton: Princeton University.

Robertson, David

1976 The OT and the Literary Critic. Philadelphia: Fortress.

Rosenberg, Joel

1993 Genesis. Pp. 3—5 in Harper Collins Study Bible, op. cit.

Skinner, John

1930 A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Genesis. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

Sternberg, Meir

1985 Poetics of Biblical Narrative. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University.

Stigers, Harold G.

1976 A Commentary on Genesis. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Whybray, R.N.

1987 The Making of the Pentateuch. Sheffield: Academic Press.

Wiseman, P.J.

1958 New Discoveries in Babylonia about Genesis. Seventh edition. London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott.

The reader interested in further study of this subject is referred to a four-part series by David T. Tsumera, Ph.D., Genesis and Ancient Near Eastern Stories of Creation and Flood. Many of the secondary references in the foregoing article are discussed in it in further detail. It was published in Bible and Spade in 1996, and posted online at the following URLs:

http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2007/02/17/Genesis-and-Ancient-Near-Eastern-Stories-of-Creation-and-Flood-An-Introduction-Part-I.aspx

http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2007/02/21/Genesis-and-Ancient-Near-Eastern-Stories-of-Creation-and-Flood-Part-II.aspx

http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2007/02/23/Genesis-and-Ancient-Near-Eastern-Stories-of-Creation-and-Flood-Part-III.aspx

http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2007/03/07/Genesis-and-Ancient-Near-Eastern-Stories-of-Creation-and-Flood-Part-IV.aspx