The Biblical record suggests that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were exceedingly wealthy men. This is borne out by the fact that they owned both donkeys and camels. The rarity of domesticated camels in the Bronze Age Near East, combined with the economic advantages enjoyed by camel owners over non-owners, along with the exclusive ability of the rich to initiate camel domestication and eventually to profit from it, provide a significant connection to the Patriarchs as described in Genesis.

This article was first published in the Winter 2006 issue of Bible and Spade.

This article was first published in the Winter 2006 issue of Bible and Spade.

Based on the overt descriptions of the Patriarchs’ wealth, some scholars have surmised that they may have been traveling merchants, using donkeys as their chief mode of transport. Sarna observed that the Patriarchs had dealings with kings, possessed slaves, retainers, silver and gold, and might possibly have participated in the international caravan trade (1966:105).

Albright, commenting on a Hebrew word used in Genesis to describe the Patriarchs’ economic activity, stated:

All the ancient versions of Genesis, from the Greek translation of the third century BC on, render the Hebrew consonantal stem SḤR (Gn 23:16; 34:10, 21; 37:28; 42:34) as “to trade (in), trader,” etc (1983:12).

He then called attention to the connection between this Hebrew term and

the cognate Old-Assyrian words from the same verbal stem, meaning in the caravan texts clearly “to trade, barter,” and “goods for barter” (Albright, 1983: 13).

Referring to Genesis 14, where Abraham leads 318 of his trained servants into battle, Albright concluded that

neither this chapter nor Genesis 23 [in which Abraham purchases land for a considerable sum of money] is intelligible unless we recognize that Abraham was a wealthy caravaneer and merchant whose relations with the native princes and communities were fixed by contracts and treaties (covenants) (1983:15).

This would certainly tie in with Macdonald’s statement that the earliest domesticated camels provided their owners with “a commercial and strategic importance to the rulers of the states around them” (1995:1357).

Of course, Albright may have overplayed his hand, reducing the Patriarchs to nothing more than donkey-riding peddlers. Scholars have rejected the more excessive aspects of Albright’s theory (cf. Couturier 1998: 194, n. 1), noting that the Patriarchal narratives never portray Abraham or his progeny as actually selling anything via their donkey ownership. Nevertheless, the proofs supplied by Albright, as well as the Genesis narrative itself, show that the Patriarchs were wealthy individuals who participated in the sedentary economy of their culture. An objection might be raised that, since Albright considered the Patriarchs to be donkey rather than camel caravaneers, his theory has no bearing on whether the Patriarchs possessed camels.

The Patriarchs’ Use of Camels

Leiman has pointed out that Genesis emphasizes Patriarchal ownership of donkeys, with camels being mentioned only rarely (1967:22). If the Patriarchs were caravaneers at all, then they were almost certainly donkey caravaneers who may have owned a comparatively small number of camels. The possibility that this conclusion is correct is reinforced by the opening verses of chapter 32, in which Jacob reunites with Esau. Before the actual meeting of the two estranged twins, Jacob sends a messenger to Esau with a list of livestock and retainers possessed by Jacob. Camels are not mentioned: “I have cattle and donkeys, sheep and goats, menservants and maidservants” (v.5).

Jacob’s departure for Canaan. “Then Jacob put his children and his wives on camels, and he drove all his livestock ahead of him, along with all the goods he had accumulated in Paddan Aram, to go to his father Isaac in the land of Canaan” (Gn 31:17–18). Author Caesar points out that only the wealthy could afford to own camels in the ancient near east.

Jacob’s departure for Canaan. “Then Jacob put his children and his wives on camels, and he drove all his livestock ahead of him, along with all the goods he had accumulated in Paddan Aram, to go to his father Isaac in the land of Canaan” (Gn 31:17–18). Author Caesar points out that only the wealthy could afford to own camels in the ancient near east.

Two verses later, camels are mentioned, but for some reason they are considered separate from the rest of Jacob’s livestock: “In great fear and distress Jacob divided the people who were with him into two groups, and the flocks and herds and camels as well.” This strange wording seems to indicate that camels were not considered part of the standard livestock inventory. In chapter 22, the sacrifice of Isaac, Abraham’s mode of transport is a donkey (v.3), not a camel. According to Genesis 34:28, the Shechemites owned donkeys but no camels. Edomite ownership of donkeys, but not camels, is mentioned in Genesis 36:24. In the story of Joseph, donkeys are the means of transportation; camels are never mentioned except as belonging to Midianite spice-traders (37:25). Thus, donkeys are unquestionably the main means of transport in the Patriarchal narratives, with camels only serving a minor role for desert travels of longer distances, in comparison. As Elat has noted:

When he [the author of Genesis] describes the wanderings of the Patriarchs in the land of Canaan, their household economy includes donkeys, cattle and sheep but no camels (cf. Gn 13:2–7; 26:14; 33:13, 17; 46:32–34; 47:1–3, 16–17). However, in describing their journeys to Aram Naharaim or to Egypt, i.e., the crossing of desert areas, he almost always relates that they use camels: Genesis 12:16 (Abraham in Egypt), Genesis 24 (Eliezer’s journey to Aram Naharaim), 30:43 (Jacob’s property in Aram Naharaim), 32:7–15 (Jacob on the way from Aram Naharaim to Canaan) (1978: 20, n.3)

The Patriarchs as Merchants

Using Albright’s merchant theory (imperfect though it may be) as a springboard, some scholars have ventured to group the Patriarchs with the tamkârum—wealthy merchants from the early second millennium BC who traveled regularly between Mesopotamia and the Levant. According to Collon and Porada:

Paul Garelli (Paris) undertook to define the best-known Assyrian term for merchant—tamk[â]rum. He found that such persons could function in a variety of ways: as officials supervising government transactions, as money lenders and even as private individuals buying and selling commodities ranging from metal to livestock. The structure of mercantile activities was shown by Mogens Larsen (Copenhagen) to have been based on family groups. Although he concentrated on the well-documented Old Assyria Colony texts [20th–17th centuries BC], it seems likely that this theory will prove to be valid for all Mesopotamian commerce (1977: 343).

To Gordon, the typical activities of the tamkârum place the Patriarchs among this merchant class:

One can say with confidence that Abraham is represented as a tamkârum from Ur of the Chaldees...Like many others from Ur, he embarked on a career in Canaan. But unlike the others, he succeeded in purchasing land and laying the foundation for his descendants’ settlement there (1962: 35).

The meeting of Isaac and Rebekah. When Abraham sent his servant to Aram Naharaim (=Paddan Aram) to find a wife for his son Isaac, “the servant took ten of his master’s camels and left, taking with him all kinds of good things from his master” (Gn 24:10). Upon the servant’s return with Rebekah, “when he [Isaac] looked up, he saw camels approaching. Rebekah also looked up and saw Isaac. She got down from her camel and asked the servant, ‘Who is that man in the field coming to meet us?’ ‘He is my master,’ the servant answered. So she took her veil and covered herself” (Gn 24:63–65). The fact that Abraham had many camels and sent his servant off with “gold and silver jewelry and articles of clothing” and “costly gifts” (Gn 24:53) indicates that Abraham was a wealthy man.

The meeting of Isaac and Rebekah. When Abraham sent his servant to Aram Naharaim (=Paddan Aram) to find a wife for his son Isaac, “the servant took ten of his master’s camels and left, taking with him all kinds of good things from his master” (Gn 24:10). Upon the servant’s return with Rebekah, “when he [Isaac] looked up, he saw camels approaching. Rebekah also looked up and saw Isaac. She got down from her camel and asked the servant, ‘Who is that man in the field coming to meet us?’ ‘He is my master,’ the servant answered. So she took her veil and covered herself” (Gn 24:63–65). The fact that Abraham had many camels and sent his servant off with “gold and silver jewelry and articles of clothing” and “costly gifts” (Gn 24:53) indicates that Abraham was a wealthy man.

He further remarked:

Abraham is repeatedly described as wealthy in gold and silver as well as in livestock and slaves. In Genesis 23:16, his commercial interests are hinted at by the phrase “current for the merchant” describing the 400 shekels of silver that he paid out. The commercial pursuits of the Patriarchs are explicitly mentioned in two different contexts confirming their commercial activities: once when the Shechemites invite Jacob’s family to join the Shechem community (Gn 34:10); the other when Joseph provisionally welcomes his brothers to settle in Egypt (Gn 42:34). On both occasions, trading privileges are offered. Abraham could afford to turn down a personal share in the plunder [resulting from his victory in battle, Genesis 14] because he had a peaceful and adequate source of income; viz., legitimate trade: an occupation that his descendants continued for at least three generations according to the text of Genesis (1962:286–87).

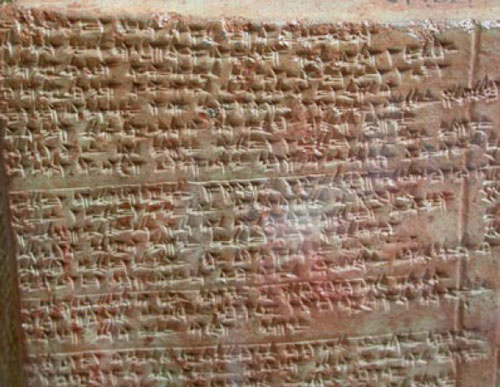

Law Code of Hammurabi (Louvre, Paris). Hammurabi, king of Babylon, began his reign in ca. 1792 BC, about a century after the death of Isaac, and ruled until 1750 BC. His famous law code was compiled toward the end of his reign. It is comprised of a prologue extolling the virtues of Hammurabi, 282 laws, and an epilogue. One of the laws indicates that tamkârum (merchants) sometimes purchased land and farmed it for profit, similar to Isaac.

Law Code of Hammurabi (Louvre, Paris). Hammurabi, king of Babylon, began his reign in ca. 1792 BC, about a century after the death of Isaac, and ruled until 1750 BC. His famous law code was compiled toward the end of his reign. It is comprised of a prologue extolling the virtues of Hammurabi, 282 laws, and an epilogue. One of the laws indicates that tamkârum (merchants) sometimes purchased land and farmed it for profit, similar to Isaac.

Economic texts from the Old Babylonian Period (ca. 1900–1600 BC) provide several parallels between the tamkârum and the Patriarchs as described in Genesis. The objection might be raised that these tamkârum were connected with donkeys, not camels, but it must be re-emphasized that the Genesis account portrays the Patriarchs as chiefly donkey owners. Camels are mentioned with comparative infrequency, with the exception of Genesis 24, where they seem to be used as status symbols (cf. Speiser 1964: 179), and have nothing to do with commerce. In fact, in no verse in Genesis do we find the Patriarchs’ camels being connected to trade in any fashion. Only the Midianites’ camels (37:25) are associated with commerce.

Tablets from the reign of Rim-Sin of Larsa (ca. 1822–1763 BC) demonstrate that, like the patrilineal configuration of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the tamkârum of Larsa operated under a father-to-son(s)-to-grandson(s) system, with brothers often acting as business partners upon taking up their father’s enterprise (Leemans, 1950: 54–55, 62). Abraham is described as owning slaves (Gn 24:2); according to Leemans, inscriptions from the reign of Hammurabi (ca. 1792–1750 BC) indicate that the tamkârum “traveled in foreign countries and frequented the slave-markets there” (1950: 9). In the same verse (24:2), Abraham sends his top-ranking slave to Mesopotamia in order to obtain a wife for Isaac. This slave heads for Mesopotamia with “ten of his master’s camels and...all kinds of good things from his master” (v. 10), evidently to dazzle a prospective bride’s family with a show of great wealth (cf. Bulliet 1990:65).

Even more similar to the Biblical episode is an Old Babylonian text in which a tamkârum sends expensive items as gifts to the family of a prospective bride for his son, precisely as Abraham sent his chief servant to Mesopotamia with gifts for Rebekah’s family in hopes of finding a suitable bride for his son Isaac:

The servant brought out gold and silver jewelry and articles of clothing and gave them to Rebekah; he also gave costly gifts to her brother and to her mother (Gn 24:53).

The contemporary Old Babylonian text reads:

2 bracelets of silver, their weight 18½ shekels, for the daughter of the tribe of Iššan (?), when the man with the daughter of the king, who was given (in marriage) at Dēr, came to Zarbilum,.....2(?) sheep, their value 2½ shekels (Leemans 1950: 74).

The Patriarchs as Landowners and Farmers

Abraham’s great wealth is most explicitly made manifest in Genesis 23, in which he purchases a burial plot from Ephron the Hittite in order to bury Sarah:

Abraham agreed to Ephron’s terms and weighed out for him the price he had named in the hearing of the Hittites: 400 shekels of silver, according to the weight current among the merchants (v. 16).

Two aspects of this verse are reflected in the economic life of contemporary tamkârum. First, an Old Babylonian trade text from Sippar features the following statement, which provides a rough parallel with the Biblical phrase: “According to the market (price) of Eshnunna he (Adad-rē’ûm) will pay silver” (Leemans 1960: 86). Second, a business contract between two tamkârum from the reign of Rim-Sin stipulates: “At the accomplishment of the journey they shall weigh out the silver and the profit from it” (Leemans 1950: 25), just as Abraham had “weighed out” for Ephron the 400 silver shekels.

Abraham’s son and heir was also a wealthy man who bore similarities to his tamkârum contemporaries. Genesis 26:13–14 states unequivocally:

The man [Isaac] became rich, and his wealth continued to grow until he became very wealthy. He had so many flocks and herds and servants that the Philistines envied him.

In Genesis 26:12, Isaac is portrayed not only as a landowner but as a highly successful farmer. At first glance, this sedentary agriculturalism does not conform to the idea that the Patriarchs bore a measure of similarity to the traveling tamkârum. However, the Code of Hammurabi clearly indicates that tamkârum often purchased land and farmed it for profit, just as Isaac “planted crops in that land and the same year reaped a hundredfold.” The Babylonian provision states:

If a citizen has taken silver from a tamkârum and has given a ploughed field for barley or sesame to the tamkârum saying: “cultivate the field and gather in the barley or the sesame that shall be extant,” then, if the cultivator produces barley or sesame in the field, in harvesting time the owner of the field shall take the barley and the sesame, that will be extant in the field, and he shall give barley for the value of the silver and its interest, that he has received from the tamkârum, together with the expenses for the cultivation to the tamkârum (Leemans 1950: 17–18).

Beduin campsite in Israel. The Genesis Patriarchs lived in tents, as evident from Genesis 12:8; 13:3, 12; and numerous other passages. Textual evidence indicates that tents were widely used in the ancient Near East as dwellings for nomadic pastoralists, military personnel, traders, and for religious shrines (Hoffmeier 2005: 196–98). Their use continues today by nomads in various parts of the world, including areas frequented by the Patriarchs such as Israel.

Elsewhere, various members of a family of tamkârum purchased several plots of improved and unimproved property in the Isin-Larsa Period (ca. 2025–1763 BC), presumably as real estate investments (Leemans 1950: 54–56). Leemans concluded of these blood-related tamkârum: “Here we have a family, the members of whose main branch show a great activity in buying real estate” (1950: 62).

The Patriarchs as Pastoral Nomads

Land ownership on the part of the Patriarchs did not preclude them from maintaining their essentially nomadic existence. According to both Genesis and contemporary records, the two lifestyles were mutually compatible. Guillén Torralba (1987:110) has called attention to the fact that Lot parted ways with Abraham and settled in Sodom (13:12), and Jacob remained in the land where his fathers had settled (i.e., Canaan, 37:1). This is in keeping with the social reality of the Patriarchal period. The Mari tablets attest the ownership of land not only by tamkârum, but by semi-nomadic Semites as well. A text from the reign of Zimri-Lim (ca. 1775–1761) reports that the grain of the Yaminite nomads had been threshed, while another tablet states that Yaminite grain grew along the banks of the Euphrates. Archives Royales de Mari (ARM) IV 1:5–28 records that men of the Yamahamu tribe were to be granted a grain field by the Mari state, presumably as a reward for services rendered. ARM V 88:5–9 similarly refers to grain fields owned by a related Semitic tribe, the Haneans, and ARM I 6 mentions Hanean grain fields along the banks of the Euphrates (Matthews 1978: 86). ARM XIII 39, sent by a certain Yasīm-Sumû to King Zimri-Lim, makes mention of “sesame [that] had been planted in the Yaminite field(s), which had already been prepared for planting” (Matthews 1978: 87–88).

Like so many other characteristics of semi-nomadic pastoralists, this aspect of the Patriarchs survives to this day among several nomadic peoples inhabiting the Old World dry zone belt, as Finkelstein and Perevolotsky have noted:

Although usually scholars divide the desert population into two segments—pastoral nomads and sedentary groups—thenomad-sedentary continuum is much more complex, composed of diverse (and changeable) socioeconomic situations, such as sedentary elements, agropastoralists, pastoralists who engage in occasional dry farming, “pure” pastoral nomads, etc. (1990: 68).

Hopkins has likewise pointed out:

In place of the desert versus the sown, there stands a portrait of an economically and politically charged continuum encompassing the desert and the sown. This notion of the integration of pastoralists and agriculturalists, of nomadic and sedentary lifestyles within the same society, has become fundamental to our understanding of the ancient Near East (1993: 205, italics original).

Concrete examples of this can be observed in the heart of the Middle East, where the Bedouins of Arabia engage in “casual agriculture” (Barfield 1993: 64) and in “regular exchange with the settled population” (Köhler-Rollefson 1993: 186). An extensive survey by Teka of Ethiopian camel-owning “agro-pastoralists [who] practice camel pastoralism and own farm plots,” revealed that the average-sized farm owned by surveyed households was 2.2 acres (0.9 ha) with the size of the farm being “directly proportional to household size” (1991: 34). The camel-owning Tuareg pastoralists of western Africa share this characteristic, despite their inherently nomadic nature. The Kel Geres sub-tribe, headed by the aristocratic, slave-owning imajeghen class, which owns the lion’s share of all livestock, including camels, also possesses

an extensive rain-fed agriculture (millet, sorghum) in the hands of dependents, who must give away part of their crops to the imajeghen, the landowners (Bernus, 1990: 154).

Like Isaac, the imajeghen are camel owners who, despite their fundamentally nomadic nature, owned and tilled land, owned slaves, and occupied the pinnacle of their society.

Another modern example can be seen in the case of the camelowning Basseri pastoralists of southern Iran. In his field study of these nomads, Barth learned that the wealthiest members of Basseri society can become even wealthier because

income from the sale of wool, butter and hides beyond what is required to pay for the household’s consumption may freely be accumulated in the form of money, and can be invested in land. The advantages offered by this investment are security, in that the land cannot be lost through epidemics or the negligence of herdsmen, and the fact that income from land is in the form of the very agricultural products which a nomad household requires (1964: 73).

He added that

sedentarization is never regarded as an ideal among the nomads; they value their way of life more highly than life in a village. But the economic advantages of land purchase are palpable: the risk of capital loss is eliminated, the profits to an absentee landowner are large, and they are in the form of products useful in a nomadic household (1964: 77)...Once a piece of land has been bought, the wealthy herd owner’s money income increases rapidly, since production in marketable goods such as wool, butter and hides continues while expenses for the purchase of agricultural produce are reduced or eliminated. If a herd owner continues to be successful, he will thus accumulate wealth more rapidly, with little promise of profit through further investment in herds, but increasingly in a form which may be directly invested in land (1964: 77–78).

Other camel-owning nomads of the Middle East are, like the Basseri, embracing agricultural sedentarism, differing from them in that this transition is becoming permanent. For example, Salzman notes that the nomads of Baluchistan

exemplif[y] the early stages of sedentarization, for while these people are becoming less mobile and are moving less often than previously, they are still nomadic by most any scholarly criterion, and as tent-dwelling, camel-riding tribesmen, they would quite adequately fulfill the popular image of Middle Eastern nomads. In addition to being examples of the early stages of sedentarization, these are cases of uncoerced sedentarization in which people have responded to political and economic changes in their environments by making decisions leading to increased sedentarization (1980: 96).

Of the Baluchi nomads, Salzman concentrated his studies most heavily on the Yarahmadzai tribe, currently called the Shah Nawazi, who inhabit Sistan and Baluchistan and number “not more than several thousand souls at the most” (1980: 97). This tribe is in the gradual process of exchanging its nomadic ways for sedentarism; its most important resources, according to Salzman, are “domesticated animals, especially goats and sheep, but also camels,” as well as domesticated date palms and “smallscale cultivation of grain and vegetables” (1980: 97). Over time, the agricultural aspect of Yarahmadzai life has increased, particularly in the cultivation of irrigated grain fields around a village that lies in the center of their traditional territory (Salzman1980: 101). As of 1980, they had not completely given up their nomadic ways. Salzman was able to report that every summer the Yarahmadzai migrated eastward on foot or by camel, leaving their animals in the care of hired hands, and tended their palm groves 120 mi (203 km) away. Ten or 12 weeks later, after the date harvest, the tribesmen returned to their winter camps and resumed their pastoral activities (Salzman 1980: 102).

A similar situation exists with the camel-owning Yoruk nomads of Anatolia. In 1969, the sedentarization process of 171 Yoruk households was studied. By 1980, fewer than 40 of those same households were still involved in pastoral nomadism (Bates 1980: 126). Interestingly, as Bates points out, the modern Yoruk have similarities with the Patriarchs as portrayed in Genesis and with the tamkârum:

Most herders among the Yoruk today belong to a small number of patronymic or lineage groups, and closely related families continue to move and rent pastures together. In this sense the organization of herding is still familial (1980: 126).

Also like the Patriarchs and tamkârum is the fact that

[a]ll large land owners, Yoruk and non-Yoruk alike, combine agriculture with other commercial ventures, usually involving some investment in businesses located in nearby towns and cities (Bates 1980: 127).

The sedentarization process, according to Bates, was led by wealthy tribal Patriarchs, who, as in the case of both the Biblical Patriarchs and the Bedouin of today, had a particular ability to deal as peers with settled governments:

In the case of Nogaylar [one of the chief towns in which the Yoruk have settled] it is apparent that lineage leaders, not marginal herders, were instrumental in organizing the joint settlement. Quite apart from the special ability of such men to deal with the government apparatus more effectively, the job of establishing the preconditions for group settlement fell to them because the acquisition of land benefited them more than it did the middle range of nomads (1980: 130).

The Patriarchs, then, shared several characteristics with the wealthy father/son tamkârum and with agro-pastoralists both of the Old Babylonian and the modern era. De Vaux pointed out the similarity between the semi-nomadic lifestyle of the Patriarchs and contemporary Semitic tribes, as described in the Mari texts (Old Babylonian Period), as well as with modern-day Near Eastern semi-nomads:

By a process of natural evolution...[Near Eastern pastoralists] become people who are no longer nomadic, but at the same time not completely sedentary. Their society is dimorphous, one in which urban and tribal characteristics are either merged with each other or else opposed to one another. It is possible to observe this double morphology in certain tribes in Syria and Palestine even today and it was undoubtedly present among the semi-nomadic people of Upper Mesopotamia during the Mari period. These sheep-raising people had flocks in grazing land, nāwum, and enclosures or encampments, hasārum, but they also had fields and they gathered in harvests. They also concluded treaties and covenants with settled peoples. They had “villages,” kaprātum, and “towns,” ālānû, both of which were clearly more or less permanent settlements occupied by a tribe or by part of a tribe near one of the towns permanently inhabited by settled people...Like the people of Mari and indeed like the semi-nomadic tribes of the Near East today, the Patriarchs began to cultivate the soil. Isaac, for instance, sowed crops and harvested them (Gn 26:12) (1978: 230–31).

The Patriarchs as Warrior-Chieftains

Not only does Genesis portray the Patriarchs as merchants, sedentary farmers, and nomads, but it makes them out to be warriors as well, able to conduct warfare and conclude peace treaties in their own right, as Gordon noted:

At first it seems strange to attribute to the Patriarchs the roles of aristocratic warriors and merchants, simultaneously. That this combination of roles is genuine, and not contrived, is borne out by the administrative texts from Ugarit, which list bdl.mrynm (400:III:6) “merchants of the charioteer warriors” and similarly bdl.mdrglm (44:VI:17) “merchants of the m.-warriors” (1962: 289).

The most notable example of this is the battle of Genesis 14, in which Abraham allies himself with a group of Syro-Canaanite petty kings against an invading confederacy of Mesopotamian rulers. Verse 14 states that Abraham was able to muster no fewer than “318 trained men born in his household” to combat the invaders. The term “trained men,” HNKM in the original Hebrew, has an Egyptian cognate, hnkw, which appears in the Execration Texts of the 19th century, a little after the time of Abraham. According to Albright, the Egyptian term refers to “retainers (of a local Palestinian or Syrian chieftain)” (1983: 15). Speiser regarded these retainers as “a large body of picked servants,” remarking: “In the present instance, Abraham appears as a powerful sheikh, which could be the aspect that was best known to his contemporaries” (1964: 104).

This is not the only instance in which Abraham is portrayed as a chieftain; in fact, Genesis 23:6 is considerably more explicit on this matter. In this verse, the Hittites from whom Abraham purchases a costly burial plot say to him, “You are a mighty prince among us.” Speiser comments that the word “prince” (Heb. nāśī’) “designates an official who has been ‘elevated’ in or by the assembly, hence ‘elected’; here an honorific epithet” (1964: 170; cf. Gordon 1962: 35). In a more general vein, Gordon remarked that

Abraham and Sarah are plainly described as the founders of a royal line (Gn 17:6, 16), and the circle in which they move is aristocratic. Socially, they deal with Pharaoh and the Philistine King of Gerar. Moreover, in role Abraham is a king, functioning as commander in chief of a coalition against another coalition of kings (Gn 14) (1966: 27).

The Genesis portrayal of Abraham as a chieftain is so overt that the ancient historian Nicolaus of Damascus went so far as to refer to him as King of Damascus (Rajak 1983: 471). If this assessment of Abraham as a chieftain (though not necessarily a full-fledged monarch) is accurate, then there is even greater reason to believe that he, his son, and his grandson could be counted among the wealthy, camel-owning elite of the Fertile Crescent society.

Muffs went to even greater lengths to demonstrate that Genesis portrays the Patriarchs as wealthy and influential enough to possess military strength on parity with the petty-kings with whom they had dealings, despite the popular image of the three men as simple pilgrims:

Although the stories of the binding of Isaac and the brave intercession over the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah tend to stamp Abraham with the seal of radical spirituality, the various Pentateuchal narrators/tradents were aware of that aspect of the Patriarch which we have called his worldly, political-military side (1983: 96).

A prime example of this can be found in Genesis 14:23 in which, after having helped the King of Sodom defeat the invading Mesopotamians, Abraham turns down his ally’s offer of booty, taking for himself “not even a thread or the thong of a sandal” (Muffs 1983: 83–84). This choice of words has a parallel in the Akkadian phrase lu hāmu lu huṣābu, “be it blade of straw or a splinter of wood,” found in the prologue to a treaty between the Hittite “Sun King,” Šuppiluliuma (early 14th century BC), and his vassal, Mattiwaza of Mitanni. The monarch in Hattusas affirms that, while the Assyrians had plundered Mitanni, Hittite troops had never taken so much as hāmu or huṣābu. Muffs concluded,

Thus we see that the clause hāmu and huṣābu is quite at home in North Syrian and Hittite international treaties. If it is found in one such context, it is likely that it will also be found in a context similar to that of Genesis 14 (1983: 84).

He then went on to note: “Just such a text” appears among contemporary Ugaritic international treaties (1983: 84). In one of the treaties, the Ugaritic petty-king Niqmaddu appeals to his overlord, Šuppiluliuma, for military aid in the face of an assault by three petty-kings by the names of Ituraddu, Addunirari, and Akietešub. The Sun King obliges, sending troops who successfully liquidate the threat to Ugarit. The booty that the three lesser monarchs had plundered from Ugarit was re-taken by the Hittite troops. Rather than keeping it for himself, the high king in Hattusas states that, in his magnanimity (and in accordance with the pact with his Ugaritic vassal), he restored all Niqmaddu’s plundered goods, keeping nothing for himself, “[be it straw or] splinter” (Muffs, 1983: 86). After examining this historical incident, Muffs observed:

Abraham seems to follow a kingly etiquette [in refusing to take any booty] since structurally his relationship to Lot and the king of Sodom is identical with the relationship between Šuppiluliuma and Niqmaddu (1983: 87).

Ras Shamra, ancient Ugarit, on the Mediterranean coast in Syria. Since 1929, thousands of clay tablets from the Late Bronze II period (ca. 1400–1177 BC) have been excavated at this site. The texts provide a wealth of information on Canaanite language, culture and religion, and consequently shed a great deal of light on the Hebrew language and many passages in the Old Testament.

Ras Shamra, ancient Ugarit, on the Mediterranean coast in Syria. Since 1929, thousands of clay tablets from the Late Bronze II period (ca. 1400–1177 BC) have been excavated at this site. The texts provide a wealth of information on Canaanite language, culture and religion, and consequently shed a great deal of light on the Hebrew language and many passages in the Old Testament.

Continuing in the same vein, Muffs called attention to Genesis 14:24, where Abraham expects that the king of Sodom provision the Patriarch’s fighting men as recompense for the assistance they had rendered the petty monarch in his struggle against the Mesopotamian confederacy. Muffs observed that a treaty between the Hittite king Muršiliš II (late 14th century BC) and his vassal, Tuppi-Tešub of Amurru, stipulated that the vassal king had to provide food and drink to Hittite troops whenever they came to his aid (1983: 89). Muffs further points to Chapter II of a treaty between Šuppiluliuma and his vassal, Aziru of Amurru, which states:

And if someone presses Aziru hard...or somebody starts a revolt, [if] you write to the king of Hatti land: “Send troops [and] charioteers to my aid!” I shall hit that enemy for you...I the Sun dispatched notables of the Hatti land, troops and charioteers of mine from the Hatti land down to the Amurru land. If they march up to towns of yours, treat them well and furnish them with the necessities of life (Muffs 1983: 89, italics added).

Muffs concluded,

Thus, when Abraham comes to the aide of his protégé Lot and of Lot’s friends (or allies), he only asks for what is rightfully his, and insists that the king of Sodom (and most probably his allies) be responsible for the rations of his soldiers (1983:89).

His point, of course, is that the Biblical tradition portrays Abraham as practically on par with a contemporary Levantine petty king, demanding that a social equal fulfill his legal obligation as stipulated by typical Late Bronze Age state treaties.

Muffs noted another similarity between second-millennium Hittite suzerainty treaties and the Patriarchal narratives. In this case, a petty kingdom named Išmerika, which was under Hittite suzerainty, was granted the following benefit:

When a city in the midst of the land [controlled by the Hittites] sins, then you, the people of Išmerika, shall step in, enter, and destroy the city and its male population. The conquered civilian population you shall keep for yourself (Muffs 1983: 90).

He called attention to the fact that the stipulations of this treaty are similar to the agreement between Abraham and the ruler of Sodom after their mutual victory: “The king of Sodom said to Abram, ‘Give me the people [nefeš] and keep the goods [rekuš] for yourself’” (Gn 14:21). Muffs commented on the Išmerika pact:

We are reminded of the Biblical distinction between rekuš (property) and nefeš (slaves), with the king of Sodom playing the role of the overlord in asking for the human population while offering Abraham the property—which in this particular tradition went to the vassal. There were obviously different traditions in vogue, but the objective distinction of categories is virtually identical in Hittite and Hebrew traditions (1983: 90).

Based on these observations, he concluded:

In short, we have seen that each element of the laws of war found in Genesis 14 has its exact parallel in good ancient Near Eastern tradition. This would seem to make Abraham not merely a pious man but a noble warrior and a politically astute maker of treaties (1983: 92, italics added).

Abraham purchases a burial plot for his wife Sarah from Ephron the Hittite. “Then Abraham rose from beside his dead wife and spoke to the Hittites. He said ‘I am an alien and a stranger among you. Sell me some property for a burial site here so I can bury my dead.’ The Hittites replied to Abraham, ‘Sir, listen to us. Bury your dead in the choicest of our tombs.’...Abraham agreed to Ephron’s terms and weighed out for him the price he had named in the hearing of the Hittites: 400 shekels of silver according to the weight current among the merchants” (Gn 23:3–6, 16).

Abraham purchases a burial plot for his wife Sarah from Ephron the Hittite. “Then Abraham rose from beside his dead wife and spoke to the Hittites. He said ‘I am an alien and a stranger among you. Sell me some property for a burial site here so I can bury my dead.’ The Hittites replied to Abraham, ‘Sir, listen to us. Bury your dead in the choicest of our tombs.’...Abraham agreed to Ephron’s terms and weighed out for him the price he had named in the hearing of the Hittites: 400 shekels of silver according to the weight current among the merchants” (Gn 23:3–6, 16).

Muffs further remarked:

[A]s we have seen, every aspect of Genesis 14 heretofore taken as an anomaly [i.e., Abraham the pilgrim vs. Abrahamthe warrior] corresponds quite exactly to inner-Biblical usage and ancient Near Eastern tradition. Once Abraham has been seen in this light, it will become clear that the other Patriarchs were also no strangers to political and military activities (1983: 95–96).

As an example, Muffs called attention to Abraham’s ability to negotiate on equal terms with the king of Gerar and that monarch’s chief general, an ability that “clearly suggests that the Patriarch was not simply a powerless resident alien of the land” (1983: 96). He was of the same mind regarding Isaac. Referring to Genesis 26, in which a wealthy Isaac enters into a non-aggression pact as a social equal of Abimelech, king of Gerar, Muffs remarked:

Although Isaac seems, at least superficially, to have been a rather colorless figure, colorless or not, he was anything but a weakling. Isaac enjoyed almost magical success in agriculture. Although the year was one of famine, “Isaac prospered in the land and reaped a hundredfold the same year” (26–13): “The man grew richer (wayyigdal) and richer (gādel) until he was very rich indeed (gādal).” Furthermore, it was Isaac’s remarkable proliferation in Abimelech’s territory which intimidated the Philistine king and caused him to say, “Go away from us, you are too numerous (‘aṣamta) for us” (v. 16), and which finally prompted Abimelech to arrange détente with the Patriarch (1983: 96–97).

Based on the Genesis narrative itself, then, the protagonists of the Patriarchal narratives are to be considered wealthy individuals who occupied the upper stratum of Near Eastern society, despite their semi-nomadic lifestyle. Further, they are unambiguously portrayed as chieftains who wield enough power, influence, and respect to be able to deal as peers with the various petty kings with whom they come in contact, while the spoken agreements into which Abraham enters with these rulers are remarkably similar to the written pacts between the Hittite Sun-Kings and their Levantine vassals. In light of such evidence, Matthews has concluded:

It is reasonable to suggest that one way the Patriarchal figures were able to obtain a measure of acceptance and respectability among the peoples of Canaan, and incidentally to demonstrate their role as heirs of a covenant with Yahweh, was through the acquisition of wealth and an impressive household. If nothing else, the “wife-sister” deception [Gn 20, 26] did operate as a means whereby Abraham and Isaac separately acquired substantial wealth (in terms of larger herds and a larger number of servants). This in turn provided them with an elevated status as prosperous, and quite formidable, leaders of migratory groups (1986: 122).

Hittite cuneiform tablet from Bogazkoy, ancient Hattusas, Turkey, ca. 1500–1180 BC (Anatolian Civilizations Museum, Ankara, Turkey). Nearly 25,000 clay tablets have been excavated at Bogazkoy over the last century. Written in an Indo-European language, they include records of the social, political, commercial, military, religious, legislative and artistic aspects of Hittite culture. There are many similarities between Patriarchal treaties in the Bible and contemporary Hittite treaty texts.

Superficially, it may not seem entirely credible that established Levantine monarchs would interact with livestock-owning agro-pastoralists, as is portrayed in the Patriarchal narratives. However, the Mari texts demonstrate that there was extensive contact between nomadic and semi-nomadic Semitic tribes on the one hand and the governors and administrators of the kingdom on the other. As cited above, de Vaux pointed out that the Mari texts record that Semitic tribes owned parcels of land such as nāwum (grazing areas), hasārum (enclosures or encampments), kaprātum (villages), and ālānum (towns) (1978: 230–231). According to Malamat, nâwum is an Akkadian term which “is used in Mari in a specific West Semitic connotation, clearly similar to Heb. nāwæ” (1967: 135). This word is employed in the Old Testament in such terms as newē rō‘īm (“shepherd’s abode”), newē ṣōn/gemallim (“sheep/camel pasturage”), neōt dæšæ (“grassy meadow”), and neōt midbār (“pasturage”) (Malamat 1967: 135; cf. de Vaux 1978: 230).

Malamat then observed:

It is this expression which would actually have described most effectively the mode of life of the Israelite tribes in the period of their wanderings and that of the Patriarchs in particular. The latter, portrayed as a semi-nomadic group, carried on a pastoral existence, pitching their tents from time to time on the outskirts of Canaanite cities, such as Shechem (Gn 12:6), Hebron (Gn 13:18), and Beersheba (Gn 26:25). We are reminded here of Mari and other Old Babylonian expressions like nawûm ša Karkamiš, nawûm ša Larsa, Sippar ù nawêšu, inferring nomadic or semi-nomadic encampments, which leaned upon urban centers and enjoyed their protection. On the other hand, the going out to an outlying nawûm from a village base (cf. the case of the Hanaeans in ARM II 48:8 ff.) is mirrored in such Biblical stories as the ranging of Jacob’s sons from their base-encampment in the Hebron valley to distant pasturages near Shechem (Gn 37:12 ff.)...[W]e encounter this expression [i.e., nāwæ], amongst others, in connection with Jacob as a metaphor newē ja‛aqob uttered by the prophet Jeremiah (10:25), the Psalmist (79:7) and the author of the Book of Lamentations (2:2) (1967: 136).

Alongside the nawûm is the alānum, a semi-permanent, villagelike settlement used by the Semitic nomads of the Mari archives. ARM III 16:5–6, for example, makes reference to “the Yaminite villages [a-la-ni] which are in the environs of Terqa” (Matthews 1978: 110). Another Mari text states:

on the instructions of Dagan and Iturmer my lord has dealt his enemies [the Yaminites] a (crushing) defeat and has transformed their cities [a-la-ni] into heaps of ruins and wasteland (Weippert, 1971: 118).

As for the term hasārum, “enclosure” or “encampment,” de Vaux pointed out that the Hebrew version, hāsēr, is found in Genesis 25:16 to denote the encampments of Abraham’s son Ishmael (1978: 232).

Such facts led him to conclude:

Quite apart from the question of the vocabulary used...the Patriarchal mode of habitation is described in Genesis in a way which is to some extent similar to that of the Mari texts. The Patriarchs, for example, set up their encampments, which could also be called nāwum, in the neighbourhood of existing urban centres. Abraham pitched his tents between Bethel and Ai (Gn 12:8). He left this site and returned to it (Gn 13:3). Leaving it again, he established his camp at Mamre near Hebron (Gn 13:18), where he was to be buried. He also lived as a nomad in the Negeb (Gn 20:1). Jacob camped near Shechem (Gn 33:18) and later at Mamre (Gn 35:27), but he moved his flocks from there to Shechem and Dothan (Gn 37:12, 17). The Patriarchs concluded treaties with city dwellers—Abraham, for instance, with Abimelech (Gn 20:15) and with the people of Hebron (Gn 23), Isaac with Abimelech (Gn 26:30), and Jacob with the people of Shechem (Gn 33:19; 34) (1978: 232).

De Vaux’s last comment regarding treaties made between the Patriarchs and sedentarist governments is also illuminated by the Mari texts, which record that that city’s royal government dealt with the leaders of Semitic agro-pastoralists as rulers in their own right, just as the kings of Sodom and Gerar dealt with Abraham and Isaac, respectively. The nomads inhabiting Idamaraṣ in the region of the Upper Habur were ruled by men whom the Mari texts called either the “kings of Idamaraṣ” or the “sheikhs (abbū) of Idamaraṣ” (Rowton 1973: 212). Zimri-Lim, king of Mari, recorded that the semi-nomadic Sim’alite tribe had previously been expelled from Talhajum, a chiefdom in Idamaraṣ which had belonged to them, but were restored to their patrimony by Zimri-Lim. The Mari king concluded a treaty with their “king” at Talhajum and appointed a royal official known as a hazannu to serve as his representative in that town (Rowton 1973: 212–13). An even higher-ranking Mari official, a merhu, is described as reporting to the king that all was well with the Sim’alites and related semi-nomadic tribes (Rowton 1973: 213).

The Mari state records also demonstrate the plausibility of Abraham’s ability to muster “318 trained men born in his household” to battle the Mesopotamian kings. One government document recorded that

2000 Suteans have assembled into a combined striking force. They have gone into the steppe pasturelands of the land of Qatanum to raid. At the same time another group of 60 Suteans went to raid near Tadmer and Našala (Matthews 1978: 106).

A record of Mari’s king, Yahdun-Lim, stated that an enemy king, Sumu-Ebuh, was aided by “the troops of the Yaminites [who] assembled to him (Sumu-Ebuh) as a single entity” (Matthews 1978: 134).

As for the formulation of treaties between the Patriarchs and the sedentarized monarchies of their day, once again the Mari tablets shed light on the historical plausibility of such transactions. A letter from one Yakīm-Addu to Zimri-Lim states:

at that time when the Yaminites came down and settled in Sagarātum I said to the king: “Do not make a treaty with the Yaminites” (Weippert 1971: 113, n. 52).

Other Mari texts include the following declarations (Weippert 1971: 114, n. 52): Yaminites” (Weippert 1971: 113, n. 52).

to make a treaty between Hanaeans and Idamaraṣ a young dog and a she-goat were produced. However, I was afraid of my lord and did not permit the dog and the goat. I had an ass of good stock killed; I brought about an alliance between the Hanaeans and the Idamaraṣ.

Asditakim, the kings of Zalmaqum (and) the sugāgū and elders of the Yaminites made a treaty in the Sîn-temple of Harran.

why have you hastily made a treaty with Zimri-Lim and the Sim’alites and come to an agreement with them?

and write to the “fathers” (šuyūh) of Idamaraṣ and to Adūna- Adad to come to you and make a treaty (and) come to an agreement with them.

Conclusion

The Biblical portrayal of the Patriarchs as wealthy agro-pastoralists who traveled between Mesopotamia and the Levant meshes well with historical reality in the Fertile Crescent. Both in the Bible and in secular history, camel domestication was almost certainly the exclusive domain of the wealthy. The Biblical narratives unequivocally portray Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as extraordinarily wealthy men who, like the tamkârum, traveled frequently, operated in family groups, owned and farmed land, and amassed fortunes in precious metals and livestock. Speiser, commenting on the mention of camels in the Patriarchal narratives, stated:

The writer could, of course, be guilty of an anachronism, or he may have chosen the camel as a symbol of Abraham’s great wealth—if widespread use of these animals was still some centuries away (1964: 179, italics added).

Based on extra-Biblical literary evidence and the Genesis narrative itself, there is every reason to accept the likelihood that the Patriarchs occupied the highest echelon of Levantine society— the only social group that was able to afford domesticated camels. When combined with the archaeological evidence supporting the plausibility of limited camel domestication in the Bronze Age from Mesopotamia to Egypt, it stands to reason that the mention of camels being owned by the wealthy, mobile, combatant Patriarchs is not an anachronism but a reflection of historical reality.

(This article is an edited version of Chapter VIII of Stephen Caesar’s MA thesis at Harvard University. The thesis is being published by Mellon Press.)

Bibliography

Albright, William F.

1983 From the Patriarchs to Moses. I. From Abraham to Moses. In The Biblical Archaeologist Reader 4, eds. Edward F. Campbell and David N. Freedman. Sheffield, England: Almond.

Barfield, Thomas J.

1993 The Nomadic Alternative. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall.

Barth, Fredrik

1964 Capital, Investment and the Social Structure of a Pastoral Nomad Group in South Persia. Pp. 69–81 in Capital, Saving and Credit in Peasant

Societies, eds. Raymond Firth and Basil S. Yamey. Chicago: Aldine.

Bates, Daniel G.

1980 Yoruk Settlement in Southeast Turkey. Pp. 124–39 in When Nomads Settle: Processes of Sedentarization as Adaptation and Response, ed. Philip C. Salzman. New York: Praeger.

Bernus, Edmond

1990 Dates, Dromedaries, and Drought: Diversification in Tuareg Pastoral Systems. Pp. 149–76 in The World of Pastoralism, ed. John G. Galaty and Douglas L. Johnson. New York: Guilford.

Bulliet, Richard W.

1990 The Camel and the Wheel. New York: Columbia University.

Collon, Dominique, and Porada, Edith

1977 23rd Recontgre Assyriologique International. Archaeology 30: 343–445.

Couturier, Guy

1998 Le problème de l’historicité des Patriarches de M.-J. Grange à R. de Vaux. In Les Patriarches et l’histoire, ed. Guy Couturier. Paris: Cerf.

Elat, Moshe

1978 The Economic Relations of the Neo-Assyrian Empire with Egypt. Journal of the American Oriental Society 98: 20–34.

Finkelstein, Israel, and Perevolotsky, Avi

1990 Processes of Sedentarization and Nomadization in the History of Sinai and the Negev. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 279: 67–88.

Gordon, Cyrus. H.

1962 Before the Bible: the Common Background of Greek and Hebrew Civilizations. New York: Harper and Row.

1966 Ugarit and Minoan Crete. New York: W. W. Norton.

Guillén Torralba, Juan

1987 Los patriarcas: historia y leyenda. Madrid: Sociedad de Educación Atenas.

Hoffmeier, James K.

2005 Ancient Israel in Sinai. New York: Oxford.

Hopkins, David. C.

1993 Pastoralists in Late Bronze Age Palestine: Which Way Did They Go? Biblical Archaeologist 56: 200–11.

Köhler-Rollefson, Ilese

1993 Camels and Camel Pastoralism in Arabia. Biblical Archaeologist 54: 180–88.

Leemans, Wilhelmus F.

1950 The Old-Babylonian Merchant: His Business and Social Position. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

1960 Foreign Trade in the Old Babylonian Period. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Leiman, Shnayer Z.

1967 The Camel in the Patriarchal Narrative. Yavneh Review 6: 16–26.

Macdonald, M. C. A.

1995 North Arabia in the First Millennium BCE. Pp. 1355–69 in Civilizations of the Ancient Near East 2, ed. Jack M. Sasson. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Malamat, Abraham

1967 Aspects of Tribal Societies in Mari and Israel. Pp. 129–38 in XVe rencontre assyriologique internationale: la civilisation de Mari, ed. Jean-Robert Kupper. Paris: Societé d’Édition “Les Belles Lettres.”

Matthews, Victor H.

1978 Pastoral Nomadism in the Mari Kingdom (ca. 1830–1760 BC). Cambridge MA: American Schools of Oriental Research.

1986 The Wells of Gerar. Biblical Archaeologist 49: 118–26.

Muffs, Yochanan

1983 Abraham the Noble Warrior: Patriarchal Politics and Laws of War in Ancient Israel. Pp. 81–107 in Essays in Honour of Yigael Yadin, ed. Géza Vermès and Jacob Neusner. Totowa NJ: Allanheld, Osmun.

Porada, Edith

1977 A Cylinder Seal With a Camel in the Walters Art Gallery. Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 36: 1–6.

Rajak, Tessa

1983 Josephus and the ‘Archaeology’ of the Jews. Pp. 465–77 in Essays in Honour of Yigael Yadin, ed. Géza Vermès and Jacob Neusner. Totowa NJ: Allanheld, Osmun.

Rowton, M. B.

1973 Urban Autonomy in a Nomadic Environment. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 32: 201–15.

Salzman, Philip C.

1980 Processes of Sedentarization Among the Nomads of Baluchistan. Pp. 95–110 in When Nomads Settle: Processes of Sedentarization as Adaptation and Response, ed. Philip C. Salzman. New York: Praeger.

Sarna, Nahum M.

1966 Understanding Genesis. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Speiser, Ephraim A.

1964 Genesis. Garden City NY: Doubleday.

Teka, Tegegne

1991 Camel and Household Economy of the Afar. Nomadic Peoples 29: 31–41.

Vaux, Roland de.

1978 The Early History of Israel. Trans. David Smith. London: Darton, Longman & Todd.

Weippert, Manfred

1971 The Settlement of the Israelite Tribes in Palestine. Trans. James D. Martin. Naperville IL: Alec R. Allenson.