The 13th century exodus-conquest theory was formulated by William F. Albright in the 1930s, based largely on Palestinian archaeological evidence, and promoted by him throughout his career.1 In the years following Albright’s death in 1971, however, evidence for the proposal dissipated and most Palestinian archaeologists abandoned the idea.2 In spite of the fact that the theory runs counter to Scripture, a number of evangelicals continue to hold to this view, prompting Carl G. Rasmussen to comment, “the Late-Date Exodus/Conquest Model has been abandoned by many scholars...it seems that currently the major adherents to the Late-Date Exodus/Conquest Model are some evangelicals!” 3 A strong advocate of the theory is Kenneth A. Kitchen, who recently gave a detailed exposition of it in his On the Reliability of the Old Testament.4

I. Basis for the 13th Century Exodus-Conquest Theory

Albright used three sites as evidence for a conquest in the late 13th century BC: Tell Beit Mirsim, which he identified as Debir,5 Beitin, identified as Bethel,6 and Lachish.7 All three were excavated in the 1930s and in each case a violent destruction layer was found which was dated to the end of the 13th century BC. At both Tell Beit Mirsim and Beitin the destruction of a relatively prosperous Late Bronze Age city was followed by a much poorer Iron Age I culture, which Albright identified as Israelite. At Lachish, on the other hand, the destruction was followed by a period of abandonment. Albright assigned a hieratic inscription dated to “regnal year four” found at Lachish to the fourth year of Merenptah and used it to date the conquest to ca. 1230 BC, based on the high Egyptian chronology in use at the time.8

A fourth major site was added to the list when Yigael Yadin excavated Hazor in the 1950s.9 Again, a violent destruction occurred toward the end of the 13th century BC. This was followed by a period of abandonment, which, in turn, was followed by a poor Iron Age I settlement.

II. Loss of the Archaeological foundation

For the 13th century exodus-conquest theory to be valid, the Palestinian destructions would have to occur prior to the fourth year of Merenptah, ca. 1210 BC, as Israel was settled in Canaan by this time according to Merenptah’s famous stela.10 A detailed analysis of the pottery associated with the destruction levels of Tell Beit Mirsim and Beitin, however, reveals that these sites were destroyed in the early 12th century, probably at the hands of the Philistines, ca. 1177 BC.11 Inscriptional evidence found at Lachish in the 1970s indicates that it was destroyed even later, ca. 1160 BC.12 Recent excavations at Hazor, on the other hand, have sustained the ca. 1230 BC date for the demise of the Late Bronze Age city.13 But was that destruction at the hands of Joshua, or Deborah and Barak?

Only three cities are recorded as having been destroyed by fire by the Israelites: Jericho (Josh 6:24), Ai (Josh 8:28), and Hazor (Josh 11:11).14 All three pose problems for a late 13th century conquest. At Jericho and Ai, no evidence has been found for occupation in the late 13th century, let alone for a destruction at that time.15 Assigning the 1230 BC destruction at Hazor to Joshua results in a major conflict with the biblical narrative. Following the 1230 BC destruction, there was no urban center there until the time of Solomon in the 10th century BC (1 Kgs 9:15).16 The defeat of Jabin, king of Hazor, by a coalition of Hebrew tribes under the leadership of Deborah and Barak is recorded in Judg 4–5. Judg 4:24 indicates that the Israelites destroyed Hazor at this time: “And the hand of the Israelites grew stronger and stronger against Jabin, the Canaanite king, until they destroyed him”. 17 If Joshua destroyed Hazor in 1230 BC, then there would be no city for the Jabin of Judges 4 to rule.

Five other sites in Cisjordan were destroyed toward the end of the 13th century BC: Gezer, Aphek, Megiddo, Beth Shan, and Tell Abu Hawam.18 The ancient name of Tell Abu Hawam is unknown, so nothing can be said relative to its role in the conquest. The other four sites, however, are singled out in the biblical narrative as cities the Israelites could not conquer.19

III. Additional Problems with a 13th Century-Exodus Conquest

1. Biblical chronology

The internal chronological data in the Hebrew Bible clearly supports a mid-15th century BC date for the exodus. The primary datum is 1 Kgs 6:1 which states, “In the four hundred and eightieth year after the Israelites had come out of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, the second month, he began to build the temple of the Lord.” Working back from Solomon’s fourth year, ca. 966 BC,20 brings us to ca. 1446 BC for the date of the exodus. The Jubilees data support an exodus date of 1446 BC as well.21

In addition, Judg 11:26 argues for a 15th century exodus-conquest. In this passage Jephthah stated in a letter to the king of Ammon, “for three hundred years Israel occupied Heshbon, Aroer, the surrounding settlements and all the towns along the Arnon.” Although it is not possible to calculate precise dates for Jephthah, various scholars have estimated the beginning of his judgeship between 1130 and 1073 BC,22 so the implication is that the tribe of Reuben had been occupying the disputed area from the Wadi Hesban to the Arnon River since ca. 1400 BC.

2. Egyptian history

Kitchen dates the conquest to 1220–1210 BC and consequently the exodus to 1260 BC,23 early in the reign of Rameses II (1279–1213 BC).24 One of the main arguments for an early 13th century date for the exodus is the mention of the name Rameses in Exod 1:11 (see below). If the Israelites built a store city named after Rameses II, then the exodus must have occurred during his reign. But if we look carefully at the chronology of the exodus events we see that this argument is flawed. Exod 1 presents a series of events: oppression (including the building of Pithom and Rameses, vs. 11), increase in Israelite population (vs. 12a), fear of the Israelites on the part of the Egyptians (vs. 12b), command to kill all newborn Israelite males (vs. 16). This series of events is then followed by the birth of Moses (Exod 2:1). Since Moses was 80 years of age at the time of the exodus (Exod 7:7), the building of Rameses would have taken place well before Moses’ birth in 1340 BC (according to the 13th century theory), long before Rameses came to the throne.25 In fact, since Rameses II was 25 years of age when he began his rule,26 the Israelites built the store city called “Rameses” before Rameses II was even born!

In addition, the Bible strongly implies that the Pharaoh of the exodus perished in the yam sûp. As the Egyptians were closing in on the Israelites at the yam sûp, the Lord said to Moses, “The Egyptians will know that I am the Lord when I gain glory through Pharaoh, his chariots and his horsemen” (Exod 14:18). Then, after the Israelites had crossed the yam sûp, “The Egyptians pursued them, and all Pharaoh’s horses and chariots and horsemen followed them into the sea” (Exod 14:23). The water then covered “the entire army of Pharaoh,” such that “not one of them survived” (Exod 14:28). More explicit are Pss 106:11, “The waters covered their adversaries; not one of them survived” and 136:15, “[the Lord] swept Pharaoh and his army into the yam sûp.” Obviously, Rameses II did not drown in the yam sûp, as he died of natural causes some 47 years after the presumed exodus date of 1260 BC.

IV. Kitchen's Defense of the 13th Century Exodus-Conquest Theory

1. Arguments for the theory

Kitchen gives three reasons why the exodus and conquest occurred in the 13th century BC.

a. Mention of Rameses in Exodus 1:11

Since the Israelites were employed to build a city which is called “Rameses” in Exod 1:11, Kitchen and those who hold to a 13th century exodus presume it was the delta capital Pi-Ramesse built by Rameses II.27 As pointed out above, however, the Israelites were employed as slave laborers to construct the store cities prior to the reign of Rameses II. It is clear, then, that the name Rameses used in Exod 1:11 is an editorial updating of an earlier name that went out of use. There was a long history of occupation in the area of Pi-Ramesse, with several names being given to the various cities there.28 The name Pi-Ramesse was in use from the time of Rameses II until ca. 1130 BC when the site was abandoned,29 possibly due to silting of the Pelusiac branch of the Nile. A new capital was then established at Tanis 12 mi. northeast.

Editorial updating of names that had gone out of use is not uncommon in the Hebrew Bible. Other examples are Bethel, named by Jacob in Gen 28:19, but used proleptically in Gen 12:8 and 13:3; Dan, named by the Danites in Judg 18:29 and used proleptically in Gen 14:14; and Samaria, named by Omri in 1 Kgs 16:24 and used proleptically in 1 Kgs 13:32. Kitchen allows for editorial updating of the name Rameses in Gen 47:11,30 and Dan in Gen 14:14,31 but not for Rameses in Exod 1:11.

b. Covenant format

Based on the formats of ancient Near East treaties, laws, and covenants from the period 2500–650 BC, Kitchen has concluded that the Sinai covenant documents of Exod, Lev, Deut, and the renewal in Josh 24, most closely match late second millennium (ca. 1400–1200 BC) Hittite treaties (see Table 1).32 However, when one looks at the formats found in the biblical covenant texts, it is seen that they are highly fluid and change continually throughout. Exodus and Leviticus are largely stipulations and religious regulations, interspersed with narrative and elements of covenant terminology. Deuteronomy is a discourse by Moses, with stipulations, and interspersed with elements of covenant terminology. The focus of Josh 24 is a call to be faithful to Yahweh, couched in covenant terminology. The biblical covenant documents do not follow any set format, as seen in Tables 2–4.33

Table 1: Second Millennium BC Covenant Formats in the Ancient Near East 69

|

ca. 1800–1700 BC |

ca. 1600–1400 BC | ca. 1400–1200 BC | |

| Mari/Leilan | North Syria | Hittites | Hittite Corpus |

| Witness/Oaths | Title | Title | Title |

| Stipulations | Stipulations | Witnesses | Historical Prologue |

| Curses | Curses | Stipulations | Stipulations |

| Oath | Deposit/Reading | ||

| Curses | Witnesses | ||

| Curses | |||

| Blessings | |||

Table 2 Covenant Format of Exodus

|

1:1–19:3a Narrative |

23:25–31 Blessings | 34:10a Preamble |

| 19:3b Preamble | 23:32–33 Stipulations | 34:10b–11 Blessings |

| 19:4 Historical Prologue | 24:1–2 Narrative | 34:12–23 Stipulations |

| 19:5–6 Blessing | 24:3a Recitation (=Reading) | 34:24 Blessings |

| 19:7 Recitation (=Reading) | 24:3b Oath | 34:25–26 Stipulations |

| 19:8 Oath | 24:4–6 Ceremony | 34:27–28 Epilogue |

| 19:9–25 Narrative | 24:7a Reading | 34:29–31 Narrative |

| 20:1 Preamble | 24:7b Oath | 34:32 Reading |

| 20:2 Historical Prologue | 24:8–11 Ceremony | 34:33–35 Narrative |

| 20:3–17 Stipulations | 24:12–18 Narrative | 35:1 Preamble |

| 20:18–21 Narrative | 25:1 Preamble | 35:2–3 Stipulations |

| 20:22a Preamble | 25:2–15 Religious Regulations | 35:4 Preamble |

| 20:22b Historical Prologue | 25:16 Deposit | 35:5–19 Religious Regulations |

| 20:23–26 Stipulations | 25:17–20 Religious Regulations | 35:20–40:19 Narrative |

| 21:1 Preamble | 25:21 Deposit | 40:20 Deposit |

| 21:2–23:19 Stipulations | 25:22–31:17 Religious Regulations | 40:21–38 Narrative |

| 23:20–23 Blessings | 31:18 Epilogue | |

| 23:24 Stipulations | 32:1–34:9 Narrative |

Table 3: Covenant Format of Leviticus

|

1:1–2a Preamble |

13:59 Epilogue | 22:33 Historical Epilogue |

| 1:2b–3:17 Religious Regulations | 14:1–2 Preamble | 23:1–2a Preamble |

| 4:1–2a Sub Preamble 1 | 14:3–31 Stipulations | 23:2b–22 Religious Regulations |

| 4:2b–5:13 Religious Regulations | 14:32 Epilogue | 23:23–24a Preamble |

| 5:14 Sub Preamble 1 | 14:33 Preamble | 23:24b–25 Religious Regulations |

| 5:15–19 Religious Regulations | 14:34–53 Stipulations | 23:26 Preamble |

| 6:1 Sub Preamble 1 | 14:54–57 Epilogue | 23:27–32 Religious Regulations |

| 6:2–7 Religious Regulations | 15:1–2a Preamble | 23:33–34a Preamble |

| 6:8 Sub Preamble 1 | 15:2b–31 Stipulations | 23:34b–42 Religious Regulations |

| 6:9–18 Religious Regulations | 15:32–33 Epilogue | 23:43 Historical Epilogue |

| 6:19 Sub Preamble 1 | 16:1–2a Preamble | 23:44 Recitation (=Reading) |

| 6:20–23 Religious Regulations | 16:2b–33 Religious Regulations | 24:1 Preamble |

| 6:24 Sub Preamble 1 | 16:34 Epilogue | 24:2–9 Religious Regulations |

| 6:25–30 Religious Regulations | 17:1–2 Preamble | 24:10–23 Narrative |

| 7:1 Sub Preamble 2 | 17:3–16 Stipulations | 25:1–2a Preamble |

| 7:2–10 Religious Regulations | 18:1–2a Preamble | 25:2b–17 Stipulations |

| 7:11 Sub Preamble 2 | 18:2b–29 Stipulations | 25:18–22 Blessings |

| 7:12–21 Religious Regulations | 18:30 Epilogue | 25:23–37 Stipulations |

| 7:22 Sub Preamble 1 | 19:1–2a Preamble | 25:38 Historical Interjection |

| 7:23–27 Religious Regulations | 19:2b–36 Stipulations | 25:39–54 Stipulations |

| 7:28 Sub Preamble 1 | 19:37 Epilogue | 25:55 Historical Interjection |

| 7:29–36 Religious Regulations | 20:1–2a Preamble | 26:1–2 Stipulations |

| 7:37–38 Epilogue | 20:2b–27 Stipulations | 26:3–12 Blessings |

| 8–10 Narrative | 21:1a Preamble | 26:13 Historical Interjection |

| 11:1–2a Preamble | 21:1b–23 Religious Regulations | 26:14–39 Curses |

| 11:2b–44 Stipulations | 21:24 Recitation (=Reading) | 26:40–44 Blessings |

| 11:45 Historical Epilogue | 22:1 Preamble | 26:45 Historical Epilogue |

| 11:46–47 Epilogue | 22:2–16 Religious Regulations | 26:46 Epilogue |

| 12:1–2a Preamble | 22:17–18a Preamble | 27:1–2a Preamble |

| 12:2b–7a Stipulations | 22:18b–25 Religious Regulations | 27:2b–33 Stipulations |

| 12:7b–8 Epilogue | 22:26 Preamble | 27:34 Epilogue |

| 13:1 Preamble | 22:27–30 Religious Regulations | |

| 13:2–58 Stipulations | 22:31–32 Epilogue |

Table 4: Covenant Format of Deuteronomy

|

1:1–2a Preamble |

13:59 Epilogue | 22:33 Historical Epilogue |

| 1:2b–3:17 Religious Regulations | 14:1–2 Preamble | 23:1–2a Preamble |

| 4:1–2a Sub Preamble 1 | 14:3–31 Stipulations | 23:2b–22 Religious Regulations |

| 4:2b–5:13 Religious Regulations | 14:32 Epilogue | 23:23–24a Preamble |

| 5:14 Sub Preamble 1 | 14:33 Preamble | 23:24b–25 Religious Regulations |

| 5:15–19 Religious Regulations | 14:34–53 Stipulations | 23:26 Preamble |

| 6:1 Sub Preamble 1 | 14:54–57 Epilogue | 23:27–32 Religious Regulations |

| 6:2–7 Religious Regulations | 15:1–2a Preamble | 23:33–34a Preamble |

| 6:8 Sub Preamble 1 | 15:2b–31 Stipulations | 23:34b–42 Religious Regulations |

| 6:9–18 Religious Regulations | 15:32–33 Epilogue | 23:43 Historical Epilogue |

| 6:19 Sub Preamble 1 | 16:1–2a Preamble | 23:44 Recitation (=Reading) |

| 6:20–23 Religious Regulations | 16:2b–33 Religious Regulations | 24:1 Preamble |

| 6:24 Sub Preamble 1 | 16:34 Epilogue | 24:2–9 Religious Regulations |

| 6:25–30 Religious Regulations | 17:1–2 Preamble | 24:10–23 Narrative |

| 7:1 Sub Preamble 2 | 17:3–16 Stipulations | 25:1–2a Preamble |

| 7:2–10 Religious Regulations | 18:1–2a Preamble | 25:2b–17 Stipulations |

| 7:11 Sub Preamble 2 | 18:2b–29 Stipulations | 25:18–22 Blessings |

| 7:12–21 Religious Regulations | 18:30 Epilogue | 25:23–37 Stipulations |

| 7:22 Sub Preamble 1 | 19:1–2a Preamble | 25:38 Historical Interjection |

| 7:23–27 Religious Regulations | 19:2b–36 Stipulations | 25:39–54 Stipulations |

| 7:28 Sub Preamble 1 | 19:37 Epilogue | 25:55 Historical Interjection |

| 7:29–36 Religious Regulations | 20:1–2a Preamble | 26:1–2 Stipulations |

| 7:37–38 Epilogue | 20:2b–27 Stipulations | 26:3–12 Blessings |

| 8–10 Narrative | 21:1a Preamble | 26:13 Historical Interjection |

| 11:1–2a Preamble | 21:1b–23 Religious Regulations | 26:14–39 Curses |

| 11:2b–44 Stipulations | 21:24 Recitation (=Reading) | 26:40–44 Blessings |

| 11:45 Historical Epilogue | 22:1 Preamble | 26:45 Historical Epilogue |

| 11:46–47 Epilogue | 22:2–16 Religious Regulations | 26:46 Epilogue |

| 12:1–2a Preamble | 22:17–18a Preamble | 27:1–2a Preamble |

| 12:2b–7a Stipulations | 22:18b–25 Religious Regulations | 27:2b–33 Stipulations |

| 12:7b–8 Epilogue | 22:26 Preamble | 27:34 Epilogue |

| 13:1 Preamble | 22:27–30 Religious Regulations | |

| 13:2–58 Stipulations | 22:31–32 Epilogue |

Kitchen has selected portions from Exod–Lev, Deut, and Josh 24, and rearranged them to match the late second millennium Hittite treaty format, with the exception of the order of blessings and curses.34 An example of this methodology is presented in Table 5. The result is an artificial format that does not correspond to the reality of the biblical texts. Kitchen has merely manipulated the biblical data to support his preconceived conclusion as to when the exodus took place. The format of the biblical material is varied and complex and cannot be dated to a particular time period based on ANE treaty formats.

Table 5: Comparison of Kitchen’s Rearranged Covenant Format With the Actual Format of Joshua 24

| Kitchen’s Rearranged Format70 | Actual Format |

| 2a Title/Preamble | 2a Preamble |

| 2b–13 Historical Prologue | 2b– 13 Historical Prologue |

| 14–15 Stipulations | 14–15 Stipulations |

| 26 Depositing Text | 16–18 Oath |

| 22, 27 Witness | 19–20 Curses |

| 20c Blessings (implied) | 21 Oath |

| 19–20b Curses | 22 Witnesses |

| 23 Stipulations | |

| 24 Oath | |

| 25–26a Depositing Text | |

| 26b–27 Witness |

Table 6 Early Second Millennium BC Law Code Formats in the Ancient Near East71

| Lipit-Ishtar(ca. 1926 BC) and Hammurabi (ca. 1760 BC) |

| Preamble |

| Prologue |

| Laws |

| Epilogue |

| Blessings |

| Curses |

Moreover, oaths, which are an important component of the biblical covenant (Exod 19:8; 24:3b, 7b; Josh 24:16–18, 21, 24), only are found in Hittite treaties from 1600–1400 BC, not in the 1400–1200 BC treaties Kitchen claims are the closest to the biblical format (see Table 1).

c. Lack of a royal residence in the delta 36

It is clear from the narrative of Exod 2–14 that there was a royal residence in the eastern delta where the Israelites were residing at the time of the exodus. Moses was rescued from the Nile and later adopted by a royal princess (Exod 2:5–10); after returning from Midian, Moses confronted Pharaoh, both in his palace and on the banks of the Nile; 37 and the Israelite foremen appeared before Pharaoh (Exod 5:15–21). Kitchen claims there was no royal center in the vicinity of Pi-Ramesse from the time of the expulsion of the Hyksos, ca. 1555 BC, until Horemhab began rebuilding, ca. 1320 BC. “Thus an exodus before 1320 would have no Delta capital to march from.” 38

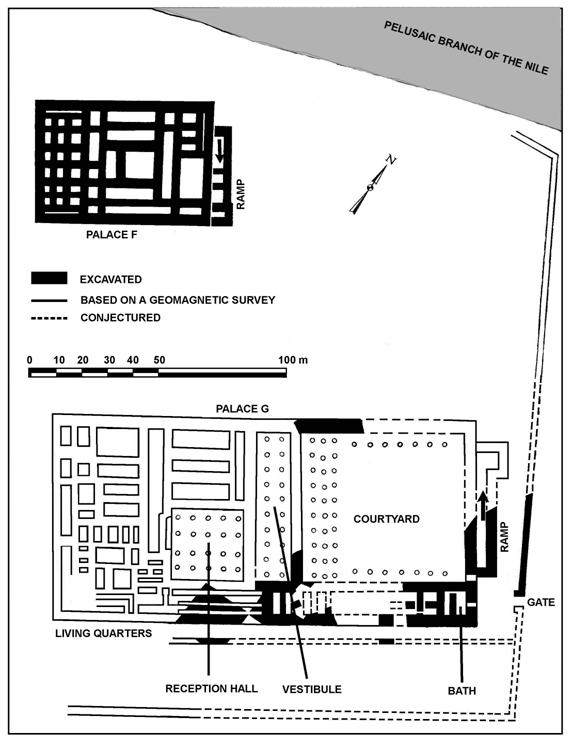

This is not the case. Excavations at Ezbet Helmi, a little over a mile southwest of Pi-Ramesse, from ca. 1990 to the present, have revealed a large royal compound occupying some 10 acres. 39 The compound was located just south of where the Pelusiac branch of the Nile flowed in antiquity, bearing out the biblical depiction of the royal palace being in close proximity to the Nile. It consisted of two palaces and other building complexes that were in use during the early 18th Dynasty. The northwestern palace, Palace F, originally built in the late Hyksos period, was constructed on a 230 x 150 ft. platform approximately 100 ft. from the riverbank. A ramp on the northeast side gave access to the palace. To the northeast of Palace F was a middle class settlement, including workshops. A series of royal scarabs were found there, covering the period of the early 18th Dynasty from its founder, Ahmosis (ca. 1570–1546 BC), to Amenhotep II (ca. 1453–1419 BC).40 Southwest of Palace F were storage rooms and possibly part of a ritual complex.41

Figure 1. Royal citadel of Moses’ time at Ezbet Helmi. Excavations by the Austrian Archaeological Institute in Cairo under the direction of Manfred Bietak have uncovered a walled-in area of ca. 10 acres enclosing a complex of buildings made of mud brick, including two major palaces, workshops, military areas, and storage and cultic facilities. (Based on Bietak, Dorner and Jánosi “Ausgrabungen 1993–2000,” figs. 4, 33 and 34b.)

The main palace, Palace G, was located 255 ft. southeast of Palace F, with an open courtyard between the two. Palace G occupied an area 259 x 543 ft., or 3 ¼ acres. To the immediate southwest were workshops and further to the southwest were city-like buildings.42 Palace G was built on a platform 23 ft. high with entry via a ramp on the northeast side. The entrance led into a large open courtyard 150 ft. square with columns on three sides. Proceeding to the southwest, one passed through three rows of columns into a vestibule that had two rows of columns. This marked the beginning of the palace proper, which probably had one or more stories above. The vestibule led into a hypostyle hall to the northwest and a reception hall with four rows of columns to the southwest. It was undoubtedly here in this reception hall where Moses and Aaron met with Pharaoh. Beyond these rooms were the private apartments of the royal family. These would have included private reception rooms, banquet rooms, dressing rooms, bathrooms and sleeping quarters.43

2. Treatment of the biblical chronological data

a. 1 Kings 6:1

To explain the 480 years of 1 Kgs 6:1, Kitchen appeals to the oft-repeated explanation that the figure is not a total time span, but rather 12 generations made up of ideal (or “full” as Kitchen says) generations of 40 years each.44 There is no basis for such an interpretation, biblical or otherwise. Nowhere in the Bible is it hinted that a “full” or ideal generation was 40 years in length. Quite the contrary, in the Hebrew Bible 40 years is often stipulated as a standard period of elapsed time.45 Moreover, there were more than 12 generations between the exodus and Solomon.46 In 1 Chr 6:33–37, 18 generations are listed from Korah, who opposed Moses (Num 16; cf. Exod 6:16–21), to Heman, a Temple musician in the time of David (1 Chr 6:31; 15:16–17). Adding one generation to extend the genealogy to Solomon results in 19 generations from the exodus to Solomon, not 12. Using Kitchen’s estimated length of a generation of ca. 25 years47 yields a total estimated time span of 475 years, a figure that compares well with the 480 years of 1 Kgs 6:1.

Umberto Cassuto made a study of the use of numbers in the Hebrew Bible.48 He discovered that when a number is written in ascending order (e.g., twenty and one hundred), the number is intended to be a technically precise figure, “since the tendency to exactness in these instances causes the smaller numbers to be given precedence and prominence.” 49 Conversely, numbers written in descending order (e.g., one hundred and twenty), are non-technical numbers found in narrative passages, poems, speeches, etc.50 The number in 1 Kgs 6:1 is written in ascending order, “in the eightieth year and four hundredth year,” and thus is to be understood as a precise number according to standard Hebrew usage, not as a schematic or symbolic number as some would have it.

b. Judges 11:26

Since there is no convenient way to dispose of the 300 year time period from the conquest to Jephthah in Judg 11:26, Kitchen resorts to an ad hominem argument; it was so much hyperbole from an “ignorant man”:

Brave fellow that he was, Jephthah was a roughneck, an outcast and not exactly the kind of man who would scruple first to take a Ph.D. in local chronology at some ancient university of the Yarmuk before making strident claims to the Ammonite ruler. What we have is nothing more than the report of a brave but ignorant man’s bold bluster in favor of his people, not a mathematically precise chronological datum.51 ...For blustering Jephthah’s propagandistic 300 years (Judg. 11:26)...it is fatuous to use this as a serious chronological datum.52

The fact of the matter is that Judg 11:26 comports well with the other chronological data in the Hebrew Bible, as well as external data, to support a 15th century exodus-conquest.

3. Treatment of the Palestinian archaeological data

a. Jericho

Kitchen attributes the lack of evidence for 13th century occupation at Jericho to erosion: “There may well have been a Jericho during 1275-1220, but above the tiny remains of that of 1400-1275, so to speak, and all of this has long, long since gone. We will never find ‘Joshua’s Jericho’ for that very simple reason.” 53 Jericho has been intensely excavated by four major expeditions over the last century and no evidence has been found, in tombs or on the tell, for occupation in the 13th century BC. Even in the case of erosion, pottery does not disappear; it is simply washed to the base of the tell where it can be recovered and dated by archaeologists. No 13th century BC pottery has been found at Jericho. A very good stratigraphic profile of the site was preserved on the southeast slope, referred to as “Spring Hill” since it is located above the copious spring at the base of the southeast side of the site. The sequence runs from the Early Bronze I period, ca. 3000 BC, to Iron Age II, ca. 600 BC, with a noticeable gap ca. 1320–1100 BC.54

b. Ai

With regard to the new discoveries at Kh. el-Maqatir,55 Kitchen comments, “The recently investigated Khirbet el-Maqatir does not (yet?) have the requisite archaeological profile to fit the other total data.” 56 The “requisite archaeological profile” for Kitchen is, of course, evidence for 13th century BC occupation. Similar to Jericho, there was a gap in occupation at Kh. el-Maqatir in the Late Bronze II period, ca. 1400–1177 BC.

c. Hazor

Kitchen attempts to deal with the problem pointed out above, namely, if Hazor was destroyed ca. 1230 BC, there would be no city for the Jabin of Judg 4 to rule and for Deborah and Barak to conquer, since Hazor was not rebuilt until the tenth century BC. His solution is that following the 1230 BC destruction, the ruling dynasty of Hazor moved their capital elsewhere: “after Joshua’s destruction of Hazor [in 1230 BC], Jabin I’s successors had to reign from another site in Galilee but kept the style of king of the territory and kingdom of Hazor.” 57 But where would this new capital be located? Kitchen does not suggest a candidate. Surveys in the region have determined that there was a gap in occupation in the area of Hazor and the Upper Galilee from ca. 1230 BC to ca. 1100 BC, ruling out Kitchen’s imaginative theory.58 The Bible clearly states that Deborah and Barak fought “Jabin, a king of Canaan, who reigned in Hazor” (Judg 4:2), who is also referred to as “Jabin king of Hazor” (Judg 4:17). The simple (and biblical) solution is that Joshua destroyed an earlier city at Hazor (see below) in ca. 1400 BC, while Deborah and Barak administered the coup de grâce in ca. 1230 BC.

V. THE BIBLICAL MODEL FOR THE EXODUS-CONQUEST

If the biblical data are used as primary source material for constructing a model for the exodus-conquest-settlement phase of Israelite history, a satisfactory correlation is achieved between biblical history and external archaeological and historical evidence, as outlined below.59

1. Date of the exodus-conquest

As reviewed above, the internal chronological data of the Hebrew Bible (1 Kgs 6:1; Judg 11:26, and 1 Chr 6:33–37) consistently support a date of 1446 BC for the exodus from Egypt and, consequently, a date of 1406–1400 BC for the conquest of Canaan. External supporting evidence for this dating comes from the Talmud. There, the last two Jubilees are recorded which allows one to back calculate to the first year of the first Jubilee cycle as 1406 BC.60

2. Support from Palestinian archaeology

Evidence from the three sites that were destroyed by the Israelites during the conquest, i.e., Jericho, Ai, and Hazor, correlates well with the biblical date and descriptions of those destructions.61 Moreover, evidence for Eglon’s palace at Jericho (Judg 3:12–30), dating to ca. 1300 BC, and the destruction of Hazor by Deborah and Barak ca. 1230 BC (Judg 4:24) during the Judges period also support a late 15th century BC date for the conquest.62

3. Support from Egyptian archaeology

a. Rameses

The area of Pi-Ramesse in the eastern delta has not only revealed evidence for a royal residence from the early 18th Dynasty, the time period of Moses according to biblical chronology, but also for a mid-19th century BC Asiatic settlement that could well be that of Jacob and his family shortly after their arrival in Egypt.63 This supports a 15th century exodus, as Jacob would had to have entered Egypt much later, in ca. 1700 BC, with a 13th century exodus.

b. Amarna Letters

The ‘apiru of the highlands of Canaan described in the Amarna Letters of the mid-14th century BC, conform to the biblical Israelites. The Canaanite kings remaining in the land wrote desperate messages to Pharaoh asking for help against the ‘apiru, who were “taking over” the lands of the king.64 Since the Israelites under Deborah and Barak were able to overthrow the largest city-state in Canaan in ca. 1230 BC65 and the Merenptah Stela indicates that Israel was the most powerful people group in Canaan in ca. 1210 BC,66 it stands to reason that the ‘apiru who were taking over the highlands in the previous century were none other than the Israelites.

c. Israel in Egyptian inscriptions

The mention of Israel in the Merenptah stela demonstrates that the 12 tribes were firmly established in Canaan by 1210 BC. It now appears that there is an even earlier mention of Israel in an Egyptian inscription. A column base fragment in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin preserves three names from a longer name list. The first two names clearly can be read as Ashkelon and Canaan, with the orthography suggesting a date in the 18th Dynasty.67 Manfred Görg has translated the third, partially preserved, name as Israel.68 Due to the similarity of these names to the names on the Merenptah stela, Görg suggests the name list may derive from the time of Rameses II, but adopting an older name sequence from the 18th Dynasty. This evidence, if it holds up to further scrutiny, would also support a 15th century BC exodus-conquest rather than a 13th century BC timeframe.

VI. Conclusions

With new discoveries and additional analysis, the arguments for a 13th century exodus-conquest have steadily eroded since the death of its founder and main proponent William F. Albright in 1971. Although Kenneth A. Kitchen has made a determined effort to keep the theory alive, there is no valid evidence, biblical or extra-biblical, to sustain it. Biblical data clearly place the exodus-conquest in the 15th century BC and extra-biblical evidence strongly supports this dating. Since the 13th century exodus-conquest model is no longer tenable, evangelicals should abandon the theory.

This article was first published in the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 48/3, (September 2005) 475-489. Posted here with permission.

Recommended Resources for Further Study

Endnotes

1. On the development of the 13th century exodus-conquest model, see John J. Bimson, Redating the Exodus and Conquest (Sheffield, England: Sheffield, 1981) 30–73; Carl G. Rasmussen, “Conquest, Infiltration, Revolt, or Resettlement?” in Giving the Sense: Understanding and Using Old Testament Historical Texts, eds. David M. Howard, Jr., and Michael A. Grisianti (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2003) 143–4.

2. Instead of considering the biblical model of a 15th century exodus-conquest, however, the majority of Palestinian archaeologists rejected the concept of an exodus-conquest altogether, in favor of other hypotheses for the origin of Israel. The most popular theory today is that Israel did not originate outside of Canaan, but rather arose from the indigenous population in the 12th century BC. For a recent discussion of this view, see William G. Dever, Who Were the Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003). For a critique, see John J. Bimson, “Merenptah’s Israel and Recent Theories of Israelite Origins,” JSOT 49 (1991): 3–29. Some scholars allow for a small “Egypt exodus group” which became the nucleus for 12th century Israel [Pekka Pitkänen, “Ethnicity, Assimilation and the Israelite Settlement,” TynBul 55.2 (2004) 165].

3. “Conquest,” 153.

4. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

5. Later excavations at Kh. Rabud have shown that this is the more likely candidate for Debir (Moshe Kochavi, “Rabud, Khirbet,” OEANE 4.401.

6. Beitin is more likely Beth Aven. See Bryant G. Wood, “The Search for Joshua’s Ai,” forthcoming.

7. William F. Albright, “Archaeology and the Date of the Hebrew Conquest of Palestine,” BASOR 58 (1935) 10–8; idem, “Further Light on the History of Israel from Lachish and Megiddo,” BASOR 68 (1937) 22–6; idem, “The Israelite Conquest of Canaan in the Light of Archaeology,” BASOR 74 (1939) 11–23.

8. “Further Light,” 23–4.

9. William F. Albright, The Biblical Period From Abraham to Ezra (New York: Harper & Row, 1963) 27–8.

10. Michael G. Hasel, “Israel in the Merneptah Stela,” BASOR 296 (1994) 45–61.

11. Bryant G. Wood, Palestinian Pottery of the Late Bronze Age: An Investigation of the Terminal LB IIB Phase (Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, 1985) 353–5, 447–8, 471–2; cf. Bimson, “Merenptah’s Israel,” 10–1.

12. David Ussishkin, “Lachish,” OEANE 3.319.

13. Kenneth A. Kitchen, “An Egyptian Inscribed Fragment from Late Bronze Hazor,” IEJ 53 (2003) 20–8.

14. Eugene H. Merrill, “Palestinian Archaeology and the Date of the Conquest: Do Tells Tell Tales?,” GTJ 3.1 (1982) 107–21.

15. On Jericho, see Thomas A. Holland, “Jericho,” in OEANE 3.223; on Ai, identified as Kh. el-Maqatir, see Bryant G. Wood, “Khirbet el-Maqatir, 1995–1998,” IEJ 50 (2000) 123–30; idem., “Khirbet el-Maqatir, 1999,” IEJ 50 (2000) 249–54; idem., “Khirbet el-Maqatir, 2000,” 246–52.

16. Doron Ben-Ami, “The Iron Age I at Tel Hazor in Light of the Renewed Excavations,” IEJ 51 (2001) 148–70.

17. All Scripture quotations in this paper are from the NIV.

18. Wood, Palestinian Pottery, 561–71; cf. Bimson, “Merenptah’s Israel,” 10–1.

19. Gezer--Josh 16:10 and Judg 1:29; Aphek--Judg 1:31; Megiddo and Beth Shan--Josh 17:11–12 and Judg 1:27.

20. Kenneth A. Kitchen, “How We Know When Solomon Ruled,” BARev 27.4 (Sept–Oct 2001) 32–7, 58.

21. Rodger C. Young, “When Did Solomon Die?” JETS 46 (2003) 599–603.

22. Bimson, Redating, 103 (1130 BC); John H. Walton, Chronological and Background Charts of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1978) 48 (1086 BC); Leon Wood, Distressing Days of the Judges (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1975) 411 (1078 BC); Kitchen, Reliability, 207 (1073 BC).

23. Reliability, 159, 307, 359.

24. Kenneth A. Kitchen, “The Historical Chronology of Ancient Egypt, A Current Assessment,” Acta Archaeologica 67 (1996) 12.

25. Rasmussen, “Conquest,” 145.

26. Peter A. Clayton, Chronicles of the Pharaohs (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1994) 146.

27. Kitchen, Reliability, 256, 309–10.

28. Bryant G. Wood, “From Ramesses to Shiloh: Archaeological Discoveries Bearing on the Exodus–Judges Period,” in Giving the Sense: Understanding and Using Old Testament Historical Texts, eds. David M. Howard, Jr., and Michael A. Grisanti (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2003) 258, 260–2.

29. Kitchen, Reliability, 255.

30. Reliability, 348, 354, 493.

31. Reliability, 335, 354, 493.

32. Reliability, 283–94.

33. David A. Dorsey sees an overall similarity to ancient Near East vassal treaties in that Gen 1:11–Exod 19:2 represents a historical introduction to the treaty, Exod 19:3–Num 10:10 is the treaty itself, and Num 10:11–Josh 24 is the historical conclusion to the treaty, but he does not push the evidence beyond that general observation (The Literary Structure of the Old Testament [Grand Rapids: Baker, 1999]) 47–48, 97–98.

34. Reliability, 284 Table 21. Blessings always follow curses in the late second millennium Hittite treaties, whereas the opposite is the case in the biblical texts. This alone shows that the biblical writers were not slavishly following a late second millennium covenant format.

35. Kitchen, Reliability, 286–7, 289, 291–3, 493.

36. Kitchen, Reliability, 310, 319, 344, 353 no. 4, 567 note 17, 635.

37. Exod 5:1–5; 7:10–3, 15–23; 8:1–11, 20–9; 9:1–5, 8–19, 27–32; 10:1–6, 8–11, 16–7, 24–9; 12:31–2.

38. Kitchen, Reliability, 310.

39. Manfred Bietak, Avaris, the Capital of the Hyksos: Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dab‘a (London: British Museum, 1996) 67–83; idem., “The Center of Hyksos Rule: Avaris (Tell el-Dab‘a), in The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer D. Oren (Philadelphia: The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 1997) 115–24; idem., “Dab‘a, Tell ed-,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt 1, ed. Donald B. Redford (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001) 353; Manfred Bietak, Josef Dorner, and Peter Jánosi, “Ausgrabungen im dem Palastbezirk von Avaris. Vorbericht Tell el-Dab‘a/Ezbet Helmi 1993–2000,” Egypt and the Levant 11 (2001) 27–119; Manfred Bietak and Irene Forstner-Mueller, “Ausgrabungen im Palastbezirk von Avaris: Vorbericht Tell el-Dhab‘a/Ezbet Helmi, Furehjahr 2003,” Egypt and the Levant 13 (2003) 39–50.

40. Bietak, Avaris, 72; Bietak, Dorner, and Jánosi, “Ausgrabungen 1993–2000,” 37.

41. Bietak, Dorner, and Jánosi, “Ausgrabungen 1993–2000,” 36.

42. Bietak, Dorner, and Jánosi, “Ausgrabungen 1993–2000,” 36–101.

43. Bietak, Dorner, and Jánosi, “Ausgrabungen 1993–2000,” 36–101; Bryant G. Wood, “The Royal Precinct at Rameses,” Bible and Spade 17 (2004) 45–51.

44. Reliability, 307. As far as I can determine, this concept originated with William F. Albright in “A Revision of Early Hebrew Chronology,” JPOS 1 (1921) 64 n. 1.

45. During the flood it rained for 40 days and nights (Gen 7:4, 12, 17); 40 days after the ark landed Noah sent out a raven (Gen 8:6); Isaac was 40 years old when he married Rebekah (Gen 25:20), as was Esau when he married Judith (Gen 26:34); the embalming of Jacob took 40 days (Gen 50:3); the spies spent 40 days in Canaan (Num 13:25; 14:34); Joshua was 40 when he went with the spies to Canaan (Josh 14:7); Israel spent 40 years in the wilderness (Exod 16:35; Num 14:33, 34; 32:13; Deut 2:7; 8:2, 4; 29:5; Josh 5:6; Neh 9:21; Ps 95:10; Amos 2:10; 5:25); Moses was on Mt. Sinai 40 days and nights the first time he received the law (Exod 24:18; Deut 9:9, 11), as he was the second time (Exod 34:28; Deut 10:10); Moses fasted 40 days and nights for the sin of the golden calf (Deut 9:18, 25); there were 40 years of peace during the judgeships of Othniel (Judg 3:11), Deborah (Judg 5:31), and Gideon (Judg 8:28); the Israelites were oppressed by the Philistines 40 years (Judg 13:1); Eli judged Israel 40 years (1 Sam 4:18); Ish-Bosheth was 40 when he took the throne following Saul’s death (2 Sam 2:10); David reigned for 40 years (2 Sam 5:4; 1 Kgs 2:11; 1 Chr 29:27), as did Solomon (1 Kgs 11:42; 2 Chr 9:30), and Joash (2 Kgs 12:1; 2 Chr 24:1); Elijah traveled 40 days and nights from the desert of Beersheba to Mt. Horeb (1 Kgs 19:8); Ezekiel lay on his right side for 40 days for the 40 years of the sins of Judah (Ezek 4:6); Ezekiel predicted that Egypt would be uninhabited for 40 years (Ezek 29:11–13); and Jonah preached that Nineveh would be overturned in 40 days (Jon 3:4).

46. Bimson, Redating, 77, 88.

47. Kitchen, Reliability, 307.

48. My thanks to Peter Gentry of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary for calling this study to my attention.

49. Umberto Cassuto, The Documentary Hypothesis and the Composition of the Pentateuch (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1961) 52.

50. Cassuto, Documentary, 52.

51. Reliability, 209.

52. Reliability, 308.

53. Reliability, 187.

54. Nicolò Marchetti, “A Century of Excavations on the Spring Hill at Tell Es-Sultan, Ancient Jericho: A Reconstruction of Its Stratigraphy,” in The Synchronisation of Civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. II, ed. Manfred Bietak (Vienna: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaftren , 2003), 295–321.

55. For references, see note 15 above.

56. Reliability, 189.

57. Reliability, 213.

58. Israel Finkelstein, The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1988) 107.

59. For an overview of the evidence, see Wood, “From Ramesses,” 256–82.

60. Young, “Solomon,” 600–1.

61. Wood, “From Ramesses,” 262–9.

62. Wood, “From Ramesses,” 271–3.

63. Wood, “From Ramesses,” 260–2.

64. Wood, “From Ramesses,” 269–71.

65. Wood, “From Ramesses,” 272–3.

66. Wood, “From Ramesses,” 273–5.

67. Manfred Görg, “Israel in Hieroglyphen,” BN 106 (2001) 24.

68. Görg, “Israel,” 25–7.

69. Kitchen, Reliability, 287 Table 25; 288 Table 26.

70. Kitchen, Reliability, 284 Table 21.

71. Kitchen, Reliability, 287 Table 24.