The problem addressed in this article is the arbitration among the three alternative views of the conquest of Ai narrative summarized in Part One. This is accomplished by testing the correspondence between the narrative in question and the material time-space context it purports to represent. Part Two...

This is Part Two of a four-part article.

Statement of the Problem

The problem addressed in this paper is the arbitration among the three alternative views of the conquest of Ai narrative summarized above. This is accomplished by testing the correspondence between the narrative in question and the material time-space context it purports to represent. The analytical method is based upon the theory of true narratives propounded by John W. Oller.4

Theological Significance

Given the prevailing scholarly opinion concerning the Conquest narrative in general, and the conquest of Ai narrative in particular, the research summarized in this paper is of great relevance to the ongoing debate concerning the factuality of the historical sections of the Old Testament, and, therefore, the theological truth value that is contained therein. Because the Conquest narrative in Joshua is the historical fulfillment of Yahweh’s unconditional covenant with the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to give the land of Canaan to their descendants, the integrity of Yahweh, the God of Israel is either established or impugned depending on whether the Conquest narrative in Joshua is factual or nonfactual.

Definition of Terms

Numerical Values

Military force element sizes in the conquest of Ai narrative, and, in fact, throughout the Hebrew Bible, are expressed in terms of eleph, or its plural form, elephim (transliterated (eleph and (elephîym, respectively). Hereafter in this paper, these two Hebrew terms are denoted eleph and elephim without diacritical markings. Furthermore, the point of controversy is over the numerical equivalence of eleph and elephim, not over their literary meaning. Therefore, to further simplify the discussion, the numerical equivalent of eleph and elephim is designated E.

This research is narrowly focused on the meaning and numerical equivalence of eleph and elephim when the terms are used to describe military forces, such as in the military censuses of Numbers 1 and 26 and the conquest of Ai narrative in Joshua 7 and 8. Within the sphere of this specific use of eleph and elephim, the customary gloss corresponding to E = 1,000 men is employed throughout the Hebrew Bible. According to Gottwald (1979: 270), this equivalence is appropriate to the time of David. However, according to the research of Briggs (2007), Fouts (1992, 1997), Gottwald (1979), Humphreys (1998, 2000), Mendenhall (1958), Petrie (1931), and Wenham (1981), the equivalence E = 1,000 men may not be appropriate to the time of Moses and Joshua. In particular, Briggs (2007: 55-57) discusses a number of problems precipitated by E = 1,000. With regard to the conquest of Ai narrative, the most serious problem is that if the army of Israel was actually of the order of 600 thousand men in accordance with the customary rendering of Numbers 1:46 & 26:51, then it would have been the mightiest fighting force in the ancient world. Compared with the number of Canaanites killed at Ai, Israel would have possessed a 50-to-1 numerical advantage!

The results of past research concerning the meaning and numerical equivalence of eleph can be summarized as follows:

a. Within the sphere of the military application, there is general agreement that eleph designates a troop of men under command of a leader. The customary gloss of E = 1,000 corresponds to the assumption that a troop size of 1,000 applies consistently throughout the Hebrew Scriptures.

b. According to Gottwald, one eleph would have been the contribution to the national military muster deriving from a particular tribal subdivision. A troop size of E = 1,000 applies to the time of David, but not necessarily to the time of Moses and Joshua.

c. According to Humphreys, the problematically large size of the army of Israel according to the censuses of Numbers 1 and 26 results from a conflation of terms in the Hebrew text. The value of E in both censuses is tribe-dependent and lies in the range of 5 to 17 men with an average value of approximately 10. This means that the army of Israel was actually of the order of 6 thousand men during the time of Moses. Gottwald, Mendenhall, Petrie, and Wenham would probably agree with Humphrey’s result, although not necessarily with his method for obtaining it.

d. Fouts argues for a hyperbolic use of numbers in the two censuses to ascribe glory to Yahweh as the reigning monarch over Israel. Since the Israelites employed a decimal numbering system, Fouts suggests that the equivalence, E = 1,000 incorporates a divine force multiplication factor of 10, which means that E should be quantified as 100.5

e. Because of the consistency with which E = 1,000 is assumed throughout the Hebrew Bible, and because of the Pauline reference to a plague incident in 1 Corinthians 10:8, this researcher favors a third resolution to the eleph problem; namely, a representational view according to which Moses, as an inspired writer of Scripture, was consistently directed to assume a divine force multiplier of 100 to represent the invincibility of the army of Israel so long as they remained faithful to the covenant with Yahweh.

Considering the proposed resolutions to the eleph problem, there exists a two-order of magnitude range of uncertainty applicable to the value of E. That is, E lies within the range of 10 to 1000. Data from the Conquest narrative in Joshua is brought to bear later in this paper in order to shrink the uncertainty band for E applicable to the time of Joshua.

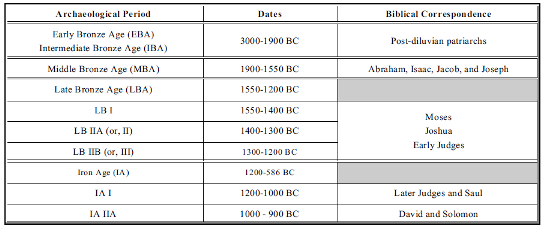

Archaeological Periods

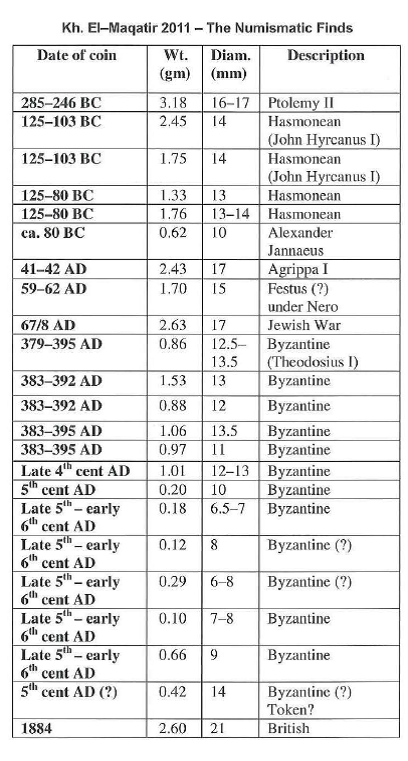

Archaeological periods pertinent to analysis of the conquest of Ai narrative in this paper are defined in Table 1. The dates and nomenclature have been synthesized from LaSor (1979), Amiran (1970), and Finegan (1998). The archaeological period nomenclature and dates defined in Table 1 are used throughout this paper.

Table 1. Archaeological Periods

Table 1. Archaeological Periods

Regnal Periods of 18th and 19th Dynasty Pharaohs

There is a tight linkage between the regnal periods of the Egyptian pharaohs and the dating of archaeological finds in Palestine. Both the 13th century date for the Exodus favored by the majority of scholars, and the 15th century date that obtains from the biblical timeline fall within the LBA and also within the time frame of the 18th and 19th dynasties. Authoritative sources for the names and regnal periods of the 18th and 19th dynasty pharaohs include the following: Hayes (1975), Wente & Van Siclen (1977), and Kitchen (1992, 1996). In Briggs (2007: 18-20) these multiple sources are compiled into a single table by means of a weighted average technique.

The Fortress of Ai

In the Hebrew text of chapters 7 and 8 of Joshua, the site in question is characterized by the Hebrew word HEBREW LETTERING, normally translated ‘city’. Frick (1977) and Hansen (2000: 36-42) present detailed analyses of this word, the central aspect of whose meaning is a fortified site. In terms of size, HEBREW LETTERING could designate a broad range of occupied sites from a watchtower or citadel to a fortified city. The configuration of the site described in Joshua 7 and 8 was probably a citadel surrounded by an outer fortification wall and gate system. The term that is selected for most precisely defining the meaning of HEBREW LETTERING in regard to the site of Ai is ‘fortress’.

The Site of Kh. el-Maqatir

This is one of the candidate sites for the fortress of Ai conquered by Joshua. It is located 3.5 kilometers east-northeast of the modern city of El Bireh, 1.6 kilometers southeast of the modern village of Beitin, and 1.1 kilometers west of et-Tell. The precise spelling of the Arabic name for this location is as follows: Khirbet el-Maqâþir. Throughout this paper, the diacritical marks are omitted for the sake of convenience and the name of the site is denoted Kh. el-Maqatir.

Definition of a Narrative

For purposes of this paper, a narrative is a verbal description of an event or an event sequence that is alleged to have taken place in a given material time-space context. An event sequence is designated an episode. Note that a delimitation is inherent in the definition; namely, only narratives that are known or alleged to be factual are considered. A fictional narrative is invented or imagined by its author; therefore, it is not known to be factual, and its author makes no claim as to its factuality. Two additional delimitations are imposed as follows: this paper only considers narratives that are, (a) written down, and, (b) linguistically coherent; in other words, well-formed in terms of syntax and grammar. Thus, the gamut of narratives to be considered include factual narratives, traditions, legends, myths, and lies. All of these terms are employed in accordance with their normal definitions. A kind of legend that is especially germane to this paper is an aetiological legend, which is a story, perhaps partially or even substantially factual, that seeks to define a cause that lies behind an observable effect (e.g., the presence of Israel in the land of Palestine, the prominent ruin of et-Tell, etc.). A kind of myth that is especially germane to this paper is a pernicious myth, which is a nonfactual story whose author intentionally and deceptively cloaks with an aura of authenticity in order to make it appear to be factual.

Definition of a True Narrative

The True Narrative Representation, or TNR, is the perfected and limiting case of a factual narrative, and it is distinguished by a triad of properties: determinativeness, connectedness, and generalizability in accordance with [Oller (1996); Oller & Collins (2000); Collins & Oller (2000)]. These properties derive from the fact that a competent observer/narrator maps an episode consisting of a sequence of one or more empirical time-space events into a linguistic representation. According to the delimitations imposed above, only true narratives that are written down are considered. The triad of TNR attributes are defined as follows:

a. Determinativeness. Through the perceptive and cognitive faculties of the narrator, the empirical particulars of the episode are mapped into language. Therefore, the surface form of the linguistic representation of the episode is motivated by the material facts of the episode as they are perceived by the narrator, and the linguistic representation determines those material facts in the sense of characterizing them and imparting meaning and relationship to them. In fact, apart from a TNR, the material facts of the episode are empty and meaningless, and therefore indeterminate. In other words, all manner of material facts, including scientific findings, are not self-determinative.

b. Connectedness. There are three aspects of this attribute. First, the components of the narrative are connected by the cognitive and linguistic faculties of the observer/narrator to the events that make up the episode. Second, the trajectory of the episode, which is embodied in the dynamic connections among the events that comprise the episode, is mapped into recognizable components of the narrative. Third, and because of the above, even as the episode is couched in a particular material time-space context, in like manner the TNR and its components are rooted in and tightly coupled to that context. Therefore, all TNRs that describe episodes that have occurred in a given material time-space context accurately reflect the particulars of that context, even though they may describe different episodes. Furthermore, since the episode of which the TNR is a mapping unfolded from event to event, with event-to-event transitions that are physically realizable, correspondingly the TNR accurately describes physically realizable event-to-event transitions.

c. Generalizability. Unlike any other kind of narrative, only TNRs are capable of supporting and sustaining generalizations. Such generalizations encompass the attributes and behaviors of any and all of the entities included in the episode, ranging from material objects to human personalities. For example, the genesis of the law of gravity undoubtedly originated with a TNR that described the falling of an object from a height.

Necessary Correspondence

This is a property of true narratives that derives from the formal properties of determinativeness and connectedness defined above. In particular, a true narrative necessarily corresponds with the material time-space context of the episode that it describes.

Empirical Correspondence

Because of the property of necessary correspondence, there ought to be an observed or empirical correspondence between a TNR and the material facts it purports to represent. Whereas necessary correspondence exists by definition, empirical correspondence is subject to the uncertainties that unavoidably attend any operation of quantitative measurement [Oller (1996: 227-229)]. Hereafter in this paper, where the term ‘correspondence’ is employed without qualification, it shall be understood as empirical correspondence rather than as necessary correspondence.

Criterial Screen

This is the particular measure of empirical correspondence that is selected for use in the present research. Through valid and correctly applied hermeneutical procedure, the parameters of the criterial screen are derived from the text of the narrative. Each of the parameters describes an aspect of the material time-space context of the narrative which must be true if the narrative is a TNR. For example, the fact that the fortress of Ai was a small site with area less than 7 acres is a criterial screen parameter which derives from the statement in Joshua 10:2 where the area of the fortress of Ai is compared with that of Gibeon.

Extending the argument to the general condition, if any given narrative is true, then all of the criterial screen parameters derived from it must also be true. In general, the greater the detail contained in the text of the narrative, the larger the number of criterial screen parameters that can be derived from the text, and, therefore, the greater the confidence factor that is associated with the result of testing the criterial screen against the material time-space context of the narrative.

Mutual Independence

Not only are the parameters of the criterial screen conditions which can be either true or false, but they are also mutually independent. That is, no parameter in the screen can be functionally linked or statistically correlated with any other parameter.

Probabilities and Confidence Factors

Suppose that it were possible to assign a probability to each of the parameters in the criterial screen. Considering the example above, one could examine a source for the sizes of Bronze Age settlements in the Benjamin hill country and determine the ratio of the number of sites whose areas are less than 7 acres divided by the total number of sites. This ratio would approximate the probability that any Benjamin hill country site selected at random would be smaller than 7 acres. If a number of parameters in the screen are found to be true, then, in accordance with the product rule for Bernoulli trials [Feller (1957: 183-198)], the joint probability of the combined event is equal to the product of the probabilities associated with each of the individual screen parameters. In fact, the result is the probability that the confluence of factors resulting in multiple screen parameters being true is a purely random occurrence. Generally, as the number of screen parameters that are true increases, the probability that such a confluence of factors is a random occurrence decreases to the point of becoming vanishingly small. In the case of a criterial screen that contains 10 parameters with a probability of 0.5 arbitrarily assigned to each, the probability that all 10 are true as a random occurrence is

2-10 = ( 1 / 1,024 ) = 0.000977

Thus, the probability that the 10 parameters being true is not a random occurrence is

1 - 2-10 = 0.999023

This exemplifies the logic that is applied later in this paper to develop a confidence factor for the result of the present research.

Reenactment

A corollary to the connectedness and generalizability properties of TNRs is this: a TNR uniquely enables the spatial reenactment of the event sequence of which the episode is comprised. In the case of the conquest of Ai narrative, the gamut of reenactment possibilities range from a detailed, “cast of thousands” portrayal of the battle to the reconstruction of one or more scenario models that fit the narrative’s description of the battle. In effect, a true narrative can be generalized back upon itself and relived in the spatial, but not the temporal, context in which the episode it describes originally occurred. This is true provided that the spatial context of the narrative can be identified and that it has not changed significantly over time. Thus, the ability to reenact the episode described in a narrative is an approach to rigorously testing the correspondence property.

Limited Cases of Reenactment

How does the reenactment property of TNRs apply in the case of the conquest of Ai episode? If the biblical narrative is a TNR, then it is possible to formulate one or more engagement scenarios involving the Israelite and Canaanite force elements described in the narrative. In particular, the traversal on foot of the routes and distances described and in the times allotted would be feasible. Thus, in the case of the conquest of Ai narrative, it is possible to probe the plausibility that a campaign such as that described in the narrative could have been carried out in actuality through a combination of analytical modeling and ground surveys of the topography in question.

Representational Uncertainty

This is a general term that includes the factors of imprecision, approximation, ambiguity, and a finite level of detail. Representational uncertainty has nothing to do with necessary correspondence, as defined above, but only with empirical correspondence. In particular, representational uncertainty can be structured and defined in terms of the criterial screen defined above. In general, the more precise and detailed a narrative, the greater the number of criterial screen parameters that can be derived from it and the lower the uncertainty. Therefore, the more precise and detailed the narrative, the greater the degree to which its factuality can be tested through comparison of its criterial screen with the material time-space context that the narrative purports to represent. The lower the precision and detail, the less amenable the narrative is to testing by this means. The level of precision and detail contained in the conquest of Ai narrative permits the formulation of a 14-parameter criterial screen.

Uncertainty Band

Representational uncertainty is encountered in deriving and evaluating the parameters of the criterial screen. For example, based upon available data, the area of Gibeon at the time of Joshua is estimated to have been 11 ±4 acres6. In this particular case, the median value of 11 6 acres is the expected value or best estimate of the size of Gibeon. The variation around the median value of ±4 acres is a measure of the representational uncertainty present in the estimate of the area of Gibeon.

Conclusiveness of the Evidence

The larger the number of parameters in the criterial screen, the more conclusive the evidence in favor of a given factuality test result. In the case of the 14-parameter criterial screen derivable from the conquest of Ai narrative in Joshua 7 and 8, if all 14 parameters are found to be true in connection with one of the candidate sites of Joshua’s Ai, then the evidence in favor of that being the correct site and the biblical narrative being factual would be conclusive beyond reasonable doubt. On the other hand, if few or none of the parameters are found to be true, then either the site has not been correctly identified, or the biblical narrative is nonfactual; in other words it would be either an aetiological legend or a pernicious myth.

DERIVATION OF THE NUMERICAL EQUIVALENT OF ELEPH

Range of Uncertainty From Past Research

The meaning of eleph, together with its plural form elephim, is one of the most baffling interpretive issues facing scholars of the Hebrew Bible. For the sake of convenience and simplicity of nomenclature, the symbol E is used to designate the numerical equivalent of either eleph or elephim. In the immediate context of the military censuses of the non-Levitical tribes recorded in Numbers 1 and 26, it has been concluded from the analysis of past research that,

eleph = Troop of fighting men

However, as to the numerical equivalent of E, the uncertainty band which results from the diversity of scholarly opinion is very large, extending over two orders of magnitude from E = 10 to E = 1,000.

Since the sizes of the various Israelite and Canaanite force elements that were involved in the two battles of Ai are described in terms of E, a central issue to correctly interpreting the conquest of Ai narrative is an accurate understanding of the numerical equivalent of E. Exegesis of the biblical texts pertinent to the conquest of Ai is brought to bear upon estimating the magnitude of E that was appropriate to the time of Joshua, and thereby narrowing the band of uncertainty to something in the order of ±50%.

The Army of Israel

The military force mustered at the command of Yahweh in Joshua 8:1-3 is described as follows: “Take all the people of war with you.” In other words, Joshua was to muster the whole army of Israel, evidently equivalent to that enumerated in the second military census of Numbers 26. Employing the analytical model of Humphreys (1998)7 as a working hypothesis, the magnitude of E under the leadership of Moses was approximately 10. At the time of the census of Numbers 26, the army of Israel numbered 5,730 fighting men organized into 593 troops, each of which consisted of between 5 and 17 men. This was the size and organizational structure of the army of Israel as it was poised on the plains of Moab opposite Jericho prior to the death of Moses. Thus, in accordance with Humphreys’ model, the number of fighting men that Joshua took with him for the second battle of Ai was 5,730. However, did Joshua organize his army with the same troop size corresponding to E . 10, or with a different troop size? In particular, does the text in the Book of Joshua provide clues as to the value of E that was appropriate to the time of Joshua?

In fact, clues as to the numerical equivalent of E can be derived from the spies’ report in Joshua 7:2-3 combined with the size of Ai as compared with that of Gibeon in accordance with Joshua 10:2.

Content of the Spies' Report

In Joshua 7:2-3, the spies commissioned by Joshua assessed the size and defensive capability of Ai in terms of the size of the attack force needed to conquer the fortress. Their recommendation was that a force of only 2E or 3E would be adequate. While I later suggest that the spies underestimated the size of Ai in terms of the number of people who were there, it is reasonable to assume that they had in mind a significant numerical advantage in Israel’s favor. Therefore, their estimate of the number of military-aged males at Ai would have been of the order of 1E so as to provide Israel with a 2-to-1 or 3-to-1 numerical advantage. Assuming that the median age of the male population of Ai was 20 years in agreement with Humphreys, the total number of males in the population of Ai would have been 2E. Assuming that the population of Ai was equally divided between males and females, the total population of Ai, according to the spies’ assessment, would have been of the order of 4E.

Implications of the Spies’ Report

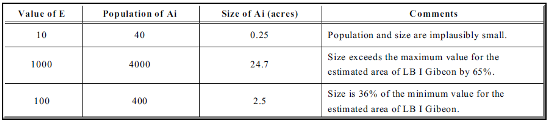

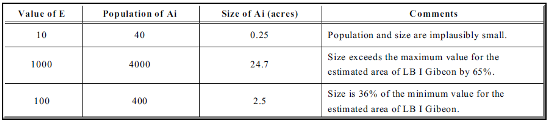

The implications of the spies’ report with respect to the population and size of Ai depend upon the value selected for E. Table 2 presents the results that obtain from three values of E: E1 = 10, the minimum value associated with the range of values appropriate to the time of Moses; E2 = 1,000, corresponding to the customary gloss for eleph throughout the Hebrew Bible; and E3 = 100, which is the geometric mean between E1 and E2. For each value of E, the total population of Ai according to the spies’ report is listed in Table 2. The size of Ai is estimated from the population by application of a population density of 162 persons per acre [Broshi & Gophna (1986)].

Table 2. Population and Size of Ai According to the Spies’ Report and for Three Values of E

Table 2. Population and Size of Ai According to the Spies’ Report and for Three Values of E

Size of Ai According to the Spies’ Report

The area of Gibeon at the time of Joshua is estimated to lie between a minimum value of 7 acres and a maximum value of 15 acres; that is, 11 ±4 acres.8 I interpret the biblical requirement in Joshua 10:2 to mean that the maximum value for the area of Ai must be less than the minimum value for the area of Gibeon; in other words, the uncertainty bands for the two areas must be disjoint with that for Ai falling below that for Gibeon. Accordingly, the maximum area for the fortress of Ai is established as 7 acres. Referring to Table 2, the equivalence of E1 = 1,000 persons yields 24.7 acres as an area estimate for the fortress of Ai which is over 3½ times the maximum value of 7 acres, and therefore blatantly contradicts the statement in Joshua 10:2.

Accordingly, the value of E appropriate to the time of Joshua must be smaller than E1 = 1,000.

It is possible to derive the maximum value for E from the report of the spies. With 162 persons per acre as the population density from Broshi & Gophna (1986), 7 acres is the maximum value for the area of Ai, and 4 as the multiple of E that represents the total population of Ai according to the spies’ estimate, then the maximum value for E is given by the following equation:

(1) EMAX = ( 162 x 7 ) / 4 = 283.5, or approximately 300

As noted in Table 2, E1 = 10 yields a population and area of Ai that is implausibly small. Therefore, the value of E applicable to the time of Joshua must lie between 10 and 300. Suppose that the minimum value for the area of Ai is taken to be 10% of its maximum value of 7 acres, that is, 0.7 acres. Based upon available data concerning the area of the candidate sites of Ai, this value appears to be very conservative in terms of being much smaller than a minimum plausible area for the fortress of Ai. Nevertheless, employing it to calculate a minimum value of E according to the pattern of equation (1),

(2) EMIN = ( 162 x 0.7 ) / 4 = 28.4, or approximately 30

Thus, the uncertainty band for the value of E applicable to the time of Joshua is estimated to be from a minimum value of E = 30 to a maximum value of E = 300. The geometric mean of 30 and 300 is

(3) EMEAN = ( 30 x 300)1/2 = 94.9, or approximately 100

Referring to Table 2, the value EMEAN = E3 = 100 yields 2.5 acres for the area of the fortress of Ai, which is 36% of the maximum allowable value of 7 acres. The areas of the two most plausible candidates for Joshua’s Ai, which are Kh. Nisya and Kh. el-Maqatir, lie within the range of 3 to 6 acres; therefore, the value of 2.5 acres is plausible, albeit on the small side. In conclusion, E = 100 is selected as the best estimate for the value of E applicable to the time of Joshua.

Size of Ai According to the Canaanites Killed in the Second Battle

According to Joshua 8:25, the total number of Canaanites killed in the second battle was 12E. From Joshua 8:17, this number included the entire population of Ai plus, evidently, the fighting men from Bethel, who had joined the men of Ai in pursuing Israel. How can the constituent parts of the 12E be estimated? Let us assume that the spies underestimated the population of Ai by 50% so that there were actually 1.5E fighting men there, and the total population, including women, children, and aged men was therefore 6E. This yields an area of 3.7 acres for the fortress of Ai, which accords very well with the measured sizes of Kh. Nisya and Kh. el-Maqatir. As a byproduct, the fighting men from Bethel would have numbered 6E.

Conclusion with Respect to the Magnitude of E

The equivalence E = 100 is adopted as being appropriate to the time of Joshua. This equivalence is subject to an estimated uncertainty band of ±50%. That is, the value of E is considered to range from a minimum value of E = 50 to a maximum value of E = 150 at the time of Joshua. While the size of the army that Joshua inherited from Moses was 5,730 fighting men, he organized this force into troops of 100, each under its own leader. The attack force deployed in the first battle of Ai was 3E = 300 men, so that the 36 men killed in action would have been 12% of this attack force. The attack force that Joshua personally led into the second battle was 5,730, or approximately 57E. The primary ambush force that Joshua deployed according to Joshua 8:3-9 was 30E = 3,000 men, which would have been 53% of the entire force. The secondary ambush force mentioned in Joshua 8:12 was 5E = 500 men. The residual attack force that Joshua led to a place of encampment north of Ai according to Joshua 8:10-13 was 22E = 2,200 men, or 39% of the total force. The total number of Canaanites that were killed in the second battle numbered 12E = 1,200 people, including the following constituent parts according to the reasoning presented above: (a) fighting men of Ai = 1.5E = 150; (b) remaining population of Ai, including women, children, and aged men = 4.5E = 450; and, (c) fighting men of Bethel = 6E = 600.

Continue to Part Three >>> Back to Part One

Endnotes

4. For a fuller discussion the theory of true narratives and its application to testing the factuality of the conquest of Ai narrative, refer to Briggs (2007: 22-26 & 72-74).

5. Refer to Briggs (2007: 60-61) for a discussion of Force Multiplication.

6. Refer to Briggs (2007: 117-118) for the derivation of this estimate.

7. Refer to Appendix A in Briggs (2007: 163-171) for a critical analysis and review of Humphreys’ model.

8. Refer to the discussion under Uncertainty Band on p. 12 of this paper and to Briggs (2007: 117-118).

References

Amiran, R. 1970 Ancient Pottery of the Holy Land, p. 12. Rutgers University Press.

Boling, R.G. 1982 The Anchor Bible: Joshua. New York: Doubleday.

Briggs, P. 2007 Testing the Factuality of the Conquest of Ai Narrative in the Book of Joshua, 5th ed. Albuquerque, New Mexico: Trinity Southwest University Press.

Bright, J. 1981 A History of Israel, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Westminister Press.

Broshi, M. & Gophna, R. 1986 Middle Bronze Age II Palestine: its settlements and population. Bulletin of American Schools of Oriental Research, Vol. 261, pp. 73-95.

Callaway, J. A. 1968 New evidence on the conquest of ) Ai. Journal of Biblical Literature , Vol. LXXXVII, No. III, pp. 312-320.

Callaway, J. A. 1970 The 1968-1969 %Ai (et-Tell) excavations. Bulletin of American Society for Oriental Research, Vol. 198, pp. 10-12.

Callaway, J. A. 1993 Article on Ai in, The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Stern, E. (Ed.), pp. 39-45. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Cassuto, U. 1983 The Documentary Hypothesis and the Composition of the Pentateuch. Translated by I. Abrahams. Jerusalem: Magnes.

Collins, S. 2002 Let My People Go: Using Historical Synchronisms to Identify the Pharaoh of the Exodus. Albuquerque, New Mexico: Trinity Southwest University Press.

Collins, S. & Oller, J. W., Jr. 2000 Biblical history as true narrative representation. The Global Journal of Classical Theology, Vol. 2, No. 2.

Feller, W. 1957 An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Finegan, J. 1998 Handbook of Biblical Chronology, p. xxxv. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc.

Finkelstein, I. & Magen, Y. (Eds.) 1993 Archaeological Survey of the Benjamin Hill Country, p. 46. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

Fouts, D. M. 1992 The Use of Large Numbers in the Old Testament, With Particular Emphasis on the Use of ‘elep. Doctoral dissertation, Dallas Theological Seminary, Dallas, Texas.

Fouts, D. M. 1997 A defense of the hyperbolic interpretation of large numbers in the Old Testament. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 377-388.

Frick, F. S. 1977 The City in Ancient Israel, pp. 25-55. Missoula, Montana: Scholars Press.

Gottwald, N. K. 1979 The Tribes of Yahweh, pp. 270-276. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books.

Hansen, D. G. 2000 Evidence for Fortifications at Late Bronze I and II Locations in Palestine. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Trinity College & Seminary, Newburgh, Indiana.

Hayes, W. C. 1975 Chronological tables (A) Egypt. Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. II, No. 2, p. 1038.

Hayes, J. H. & Miller, J. M. (Eds.) 1977 Israelite and Judean History. Philadelphia: Trinity Press International.

Humphreys, C. J. 1998 The number of people in the Exodus from Egypt: decoding mathematically the very large numbers in Numbers I and XXVI. Vetus Testamentum, Vol. 48, pp. 196-213.

Humphreys, C. J. 2000 The numbers in the Exodus from Egypt: a further appraisal. Vetus Testamentum, Vol. 50, pp. 323-328.

Kaiser, W. C., Jr. 1987 Toward Rediscovering the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House.

Kelso, J. L., & Albright, W.F. 1968 The excavation of Bethel. In Kelso, J.L. (Ed.), Annual of American Schools of Oriental Research, Vol. XXXIX, Cambridge.

Kenyon, K. M. 1957 Digging Up Jericho. London.

Kenyon, K. M. 1960 Archaeology in the Holy Land. London: Benn.

Kitchen, K. A. 1992 History of Egypt (chronology). The Anchor Bible Dictionary, Freedman, D. N. (Ed.), Vol. 2, pp. 322-331. New York: Doubleday.

Kitchen, K. A. 1996 The historical chronology of ancient Egypt: a current assessment. Acta Archaeologica, Vol. 67, pp. 1-13.

LaSor, W. S. 1979 Article on archaeology in, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Bromiley, G. W. (Gen. Ed.), Vol. One, pp. 235-244. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Livingston, D. P. 1970 Location of Bethel and Ai Reconsidered. Westminister Theological Journal, Vol. 33, pp. 20-24.

Livingston, D. P. 1971 Traditional site of Bethel Questioned. Westminister Theological Journal, Vol. 34, pp. 39-50.

Livingston, D. P. 1994 Further considerations on the location of Bethel at El-Bireh. Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol. 126, pp. 154-159.

Livingston, D. P. 1999 Is Kh. Nisya the Ai of the Bible? Bible and Spade, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 13-20.

Mendenhall, G. E. 1958 The census of Numbers 1 and 26. Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 77, pp. 52-66.

Miller, J. M. & Hayes, J. H. 1986 A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Philadelphia: The Westminister Press.

Na’aman, N. 1994 The ‘Conquest of Canaan’ in the Book of Joshua and in History. In Finkelstein, I. & Na’aman, N. (Eds.). From Nomadism to Monarchy. Washington: Biblical Archaeology Society.

Oller, J. W., Jr. 1996 Semiotic theory applied to free will, relativity, and determinacy: or why the unified field theory sought by Einstein could not be found. Semiotica, Vol. 108, No. 3 & 4, pp. 199-244.

Oller, J. W., Jr. & Collins, S. 2000 The logic of true narratives. The Global Journal of Classical Theology, Vol. 2, No. 2.

Petrie, W. M. F. 1931 Egypt and Israel, pp. 40-46. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Originally published in 1910.

Wenham, G. J. 1981 Numbers: An Introduction and Commentary, pp. 56-66. Downers Grove, Illinois: Inter-Varsity Press.

Wente, E. & Van Siclen, C., III 1977 A chronology of the New Kingdom, Table 1, p. 218. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization No. 39. Chicago: The Oriental Institute.

Wood, B. G. 2000a Khirbet el-Maqatir, 1995-1998. Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 50, pp. 123-130. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Wood, B. G. 2000b Khirbet el-Maqatir, 1999. Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 50, pp. 249-254. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Wood, B. G. 2000c Kh. El-Maqatir 2000 Dig Report. Bible and Spade, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 67-72.

Zevit, Z. 1985 The Problem of Ai: New Theory Rejects the Battle as Described in the Bible but Explains How the Story Evolved. Biblical Archaeology Review, Vol. XI, No. 2, pp. 58-69.