Dr. Erez Ben-Yosef and Dr. Lidar Sapir-Hen of Tel Aviv University's Department of Archaeology and Near Eastern Cultures have used radiocarbon dating in an attempt to pinpoint the time when domesticated camels arrived in the southern Levant, pushing the standard estimate from the 12th down to the 10th century BC. The findings, published recently in the journal Tel Aviv, are being used to argue that camels were first used in the mining operations near the end of the 10th century BC. They state that this is the first evidence of domesticated camels in ancient Israel. Such proclamations erroneously extrapolate the findings of the research far beyond what the actual data proves. In reality, there is abundant evidence that the Bible's mention of camels as early as the time of Abraham is contextually and historically accurate. In this article, TM Kennedy demonstrates the accuracy of the biblical texts in their historical setting as it pertains to camels.

Introduction

The single-humped camel, Camelus dromedarius, and the double-humped camel, Camelus bactrianus, have been important for use as a draft animal, saddle animal, food source, and even textile source in the Near East for thousands of years. The dromedary is the most common in the Near East, although both species have been in use by humans in the region for a long period of time. Although many claim there is a consensus within archaeological circles, in reality scholars debate exactly when the camel was first domesticated in the Near East-for any purpose. The theories range from as late as the 9th century BC to as early as the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, depending on the availability of data, interpretation of data, and personal opinions, leaving a large range of years in dispute.

Typically, ancient Near Eastern scholars-especially those focusing on the Levant or on archaeology related to the Bible-subscribe to a date for the domestication of the camel between the end of the 12th century BC to sometime in the 9th century BC. Redford, when discussing a reference concerning camel domestication in the book of Judges, writes 'anachronisms do indeed abound…camels do not appear in the Near East as domesticated beasts of burden until the ninth century B.C.' 1 A radiocarbon study of select camel bones from the Aravah valley in the southern Levant extrapolates that the findings may indicate domesticated camels were not present anywhere in the region until the end of the 10th century BC.2 Finkelstein and Silbermann state, 'We now know through archaeological research that camels were not domesticated as beasts of burden earlier than the late second millennium and were not widely used in that capacity in the ancient Near East until well after 1000 BCE.' 3 This stance is similar, but allowing for the possibility of a few centuries earlier on a much smaller scale. Although several scholars assert that camels were not domesticated in the ancient Near East until about the 9th century BC, it may be significant that 'by the middle of the ninth century cavalries were obviously well established, since at the Battle of Qarqar Shalmaneser III faced many men on horseback (and some on the backs of camels).' 4 This use of domesticated camels in the context of the 9th century BC cavalry battle in the Levant suggests that camels had been domesticated for a significant length of time prior to the conflict, as use of a camel in warfare indicates a tradition of reliability in addition to complex training.

Domestic camels on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, British Museum. Credit: TM Kennedy

Domestic camels on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, British Museum. Credit: TM Kennedy

Albright stated that 'our oldest certain evidence for the domestication of the camel cannot antedate the end of the twelfth century B.C.' 5 His argument was based on a belief that 'the oldest published reference to the camel dates from the eleventh century B.C.,' referring to an Assyrian text.6 This text is the Broken Obelisk, probably from the reign of Ashur-bel-kala (1074-1056 BC), but some of the reports on it may refer to the time of Tiglath Pileser I (1115-1077 BC). The obelisk resides in the British Museum, and the inscription mentions the breeding of Bactrian camels. Rosen and Saidel take a similar stance regarding the earliest reliable date for the presence of domesticated camels, especially in the Levant.7 These have been the dates assumed throughout many studies, and thus the general consensus became that there were no domesticated camels in the ancient Near East prior to the Iron Age.

Since many scholars state that camels were not domesticated until perhaps as late as the 9th century BC, several references to domestic camels in the Bible have been considered anachronistic. Numerous instances of camels being used as beasts of burden prior to the 9th century or even 12th century BC within the Old Testament books of Genesis, Exodus, Judges, and Job would appear to be inaccurate, if archaeological data indicated that camels were not being used in a domesticated context prior to this period. The word 'camel' (???) is used in a domesticated sense 22 times in Genesis (Genesis 12:16, 20:10-64, etc.), once in Exodus (Exodus 9:3), 4 times in Judges (Judges 6:5, 7:12, 8:21, 8:26) and 3 times in Job (Job 1:3, 1:17, 42:12).8 It is clear that in these books camels are used in a domesticated sense, and often as beasts of burden.9 Geographically, these references indicate the presence or use of domesticated camels in the areas of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Arabia, and the Levant. Chronologically, the references to camels in the books all take place in a context prior to the late 12th century BC, and certainly prior to the 9th century BC date suggested by some scholars.

As an answer to these ancient Bible texts that claim the Bronze Age use of domesticated camels, a common explanation offered is that later scribal substitution of 'camel' for some other pack animal such as a donkey occurred. Yet, concerning the subsequent substitution of camel for another animal, Millard argues that a later writer making modifications in the text in an attempt to emphasize the wealth of the patriarchs would not substitute 'camel' but instead 'horse,' since horses were expensive and valuable during the Iron Age.10 This is a plausible assertion that demonstrates a textual emendation from 'horse' or another animal to 'camel' would be highly unlikely. More clear evidence, however, comes from Bronze Age texts. For example, cuneiform texts which suggest the use of domesticated camels in the Bronze Age could not be attributed to later scribal emendations or copying error. Still, the general consensus by ancient Near Eastern scholars over the last several decades has been that camels were not domesticated in the area until the Iron Age.

Camels as Imports from the East

Assuming that those who subscribe to a 12th century or later view for the domestication of the camel in the ancient Near East are correct, there is still the possibility that domesticated camels existed in the Near East before the 12th century as imports from the East, instead of being locally domesticated. Daniel Potts presents this possibility, suggesting that camels were domesticated in the area of eastern Iran long before the 12th century BC, and then brought west for trade.11 Therefore, domesticated camels may have been in use in the Near East prior to the 12th century BC and the beginning of the Iron Age through trade, while the people of the Near East may soon have learned to domesticate their own local camels.

Evidence for Early Camel Domestication in the Ancient Near East

However, numerous discoveries have turned up in several areas of the Near East arguing for a much earlier domestication date. First, an Aramean camel-rider carving on display in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, dated to the 10th century BC, conflicts with the latest suggested 9th century BC domestication. The artifact was found at Tell el-Halaf in Mesopotamia by Max von Oppenheim, who had originally dated the piece to the early 3rd millennium BC.12

Aramean rider on a camel. Walters Art Gallery. Credit: David Q. Hall

Aramean rider on a camel. Walters Art Gallery. Credit: David Q. Hall

This carving predates the theory of several scholars by at a least century, and forces a recalibration of their theory. Moving past the 9th century BC theory and examining the viability of a 12th century BC theory, similar problems are discovered. In Lower Egypt, Petrie found a dromedary statuette which appears to be carrying two water jars. Based on provenance and the style of the pottery and the water jars, Petrie concluded the artifact was in fact from the 19th Dynasty, dated between 1292-1190 BC.13

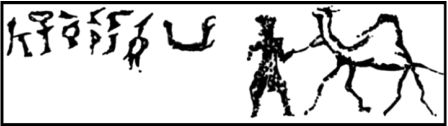

An even earlier attestation from Egypt, again in the form of ancient petroglyphs representing domesticated camels, was discovered next to Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions on a rock face in the Wadi Nasib.14 To the right of the inscriptions are two 'distinctive animal petroglyphs-camels-that were represented as walking caravan style across the rock to the right (easterly direction).' 15 Although the first camel has been partially defaced, the trailing camel is distinct and easily identifiable as a dromedary. 'The lead camel appears to be followed by a walking man. A second walking man is clearly leading the trailing camel.' 16 Next to these inscriptions is an Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription translated 'Year 20 under the majesty of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Nema're', son of Re' Ammenemes, living like Re' eternally.' 17

Proto-Sinaitic petroglyph of a man leading a dromedary camel at Wadi Nasib. Credit: Younker 1997.

Proto-Sinaitic petroglyph of a man leading a dromedary camel at Wadi Nasib. Credit: Younker 1997.

With boundaries of Ammenemes III, a 12th Dynasty ruler in the 19th century BC, and the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions in the 15th century BC, with no current evidence for activity in the area much later than ca. 1500 BC, the camel petroglyphs could be dated to sometime in between.18,19 Therefore, the archaeological remains indicate that humans began using camels as pack animals in this area no later than the 16th century BC.

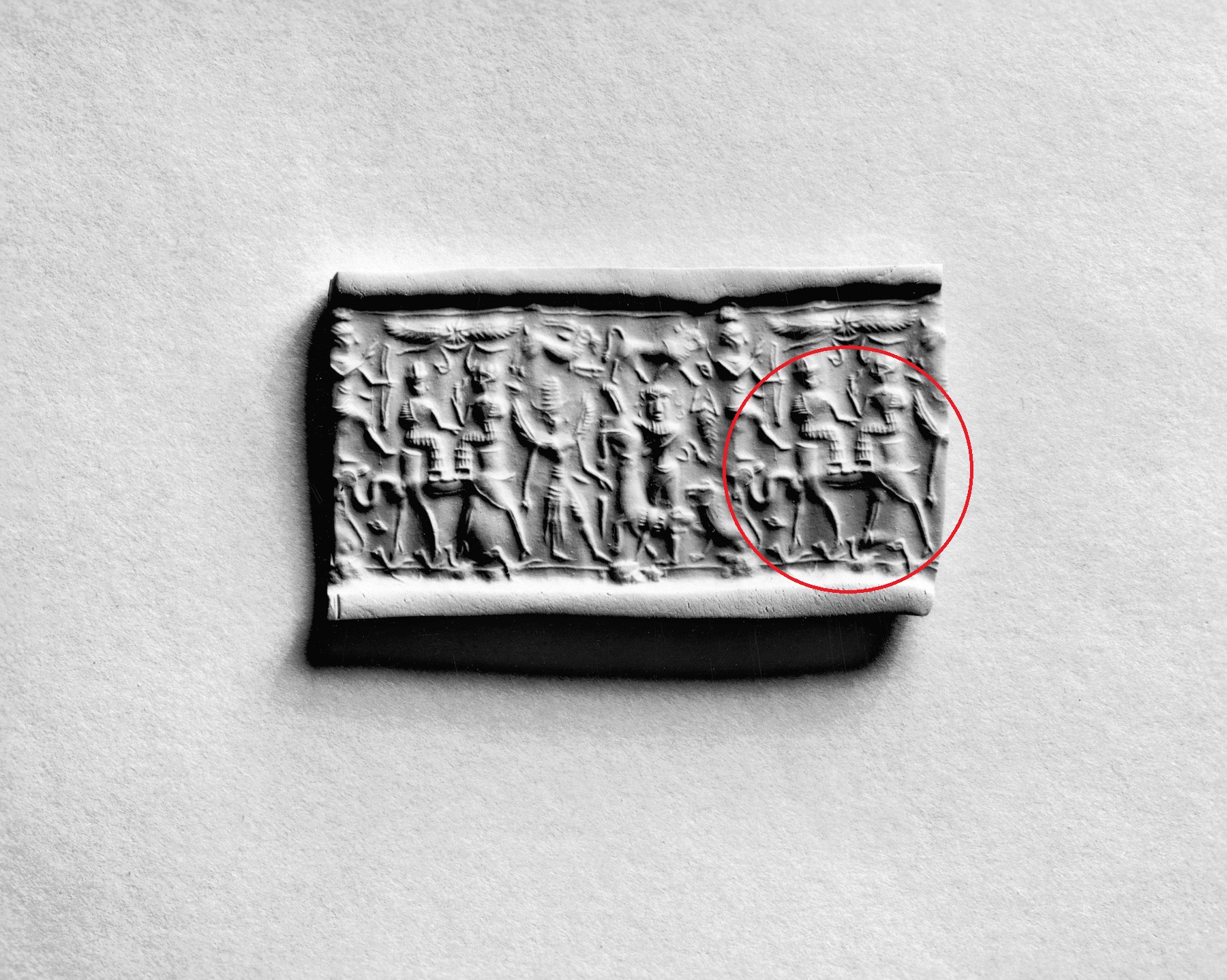

From the Levant, a Syrian cylinder seal dated ca. 1800 BC depicts two small figures riding on a two-humped camel.20 It has been argued that the riders are gods, not humans, due to iconography found on other parts of the seal such as a divine star and a winged deity. While the artist may have been depicting the couple riding on the camel as gods, it is also possible that they are a royal human couple. Further, a depiction of gods riding upon a camel does not invalidate the idea that humans were riding upon camels at the time, but rather supports it by suggesting the idea came from reality. If the camel were a mythological creature such as a sphinx, then the scene would support a fanciful idea of the riders. However, at least six real animals are depicted on the seal, and the only clearly supernatural figure appears to be the winged deity. Thus, the riders on the seal suggest that riding upon camels was known in the Levant as early as 1800 BC. In Macdonald's analysis of camel warfare in ancient Arabia, he notes that it was customary for two riders to share a single camel. He found that 'they would use the camel to get them to and from the battle, often riding two to a camel, but would dismount to fight. If defeated, they would remount and flee, again often two to a camel, with one rider trying to ward off the pursuers with his bow.' 21 While the knowledge of this practice comes from a later period, it demonstrates the plausibility of the two riders sharing the camel being men rather than gods.

Syrian cylinder seal depicting a Bactrian camel. Walters Art Museum. (Click to Enlarge)

Syrian cylinder seal depicting a Bactrian camel. Walters Art Museum. (Click to Enlarge)

Another figurine that appears to suggest an early date for camel domestication is found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (53.117.1). The figurine is a small copper alloy statue of a Bactrian camel, equipped with what appears to be some type of harness. The artifact is dated to between the late 3rd and early 2nd millennium BC, from Bactria-Margiana. Thus, there is evidence indicating early camel domestication from several geographical areas of the ancient Near East.

Bactrian camel statue from the third to second millenium BC in theMetropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Credit: TM Kennedy

Bactrian camel statue from the third to second millenium BC in theMetropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Credit: TM Kennedy

Inscriptional and Documentary Evidence

The English word for camel comes from the Latin camelus, which comes from the Greek kamelos (καμελος), which comes from the Hebrew gamal (???). The Hebrew gamal is closely associated with another Semitic form, the Akkadian gammalu. Many Akkadian words have their origins in the Sumerian language, and gammalu is one of the words which contains a Sumerian ancestor in its logograms. Regular usage of Sumerian pre-dates the late views for the domestication of the camel, and it is interesting to note that Sumerian actually has two words for camel, (ANSE.A.AB.BA; ANSE.GAM.MAL), meaning donkey or ass of the sea, and donkey or ass of the mountains, respectively.22 Potts discusses the differences between the Bactrian and the dromedary camel, demonstrating how the dromedary is more suited to the desert and arid climates, while the Bactrian is more suited to the mountains and colder weather.23 These two variations of the Sumerian word for camel may be a reflection upon the differences of the Bactrian and the dromedary. Although Sumerian having a word for an animal by no means suggests that it was domesticated in that society, it demonstrates that the animal was known by the civilization at an early date. Yet, neither species of camel originates in Sumerian areas, suggesting the geographical spread of the species. The presence of a word for camel associated with the domesticated pack animal the donkey suggests the possibility that the camel was used in a domestic context during in the 2nd millennium BC or earlier, although perhaps infrequently.

However, more than merely ambiguous textual evidence exists. Three texts dating to approximately the same period as the Patriarchs attest to domesticated camel use. A Sumerian text found at Nippur from the Old Babylonian period, ca. 1950-1600 BC, 'gives clear evidence of the domestication of the camel by that time, for it alludes to camel's milk.' 24 Another text mentions 'a Camel in a list of domesticated animals during the Old Babylonian period (1950-1600 BC) in a Sumerian Lexical Text from Ugarit.' 25 The third text comes from a cuneiform ration list found at Alalakh in the Level VII Middle Bronze Age city. This particular Alalakh tablet (269:59) reads '1 SA.GAL ANSE.GAM.MAL, 'one (measure of) fodder-camel.'' 26 Here we have a text stating that camels in the city were given food rations, an action which would only be done for a domesticated animal. The aforementioned texts appear to be clear evidence from the 2nd millennium BC for domesticated camels in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the northern Levant.

Yet, evidence for camel domestication may be found even into the 3rd millennium BC. A second set of relevant camel petroglyphs in Egypt come from a rock carving near Aswan and Gezireh in Upper Egypt. This carving depicts a man leading a dromedary camel with a rope, along with 7 hieratic characters to the left of the man.

Third millenium BC Egyptian petroglyph of a man leading a dromedary camel. Credit: Ripinsky 1985.

Third millenium BC Egyptian petroglyph of a man leading a dromedary camel. Credit: Ripinsky 1985.

The entire carving was dated to the 6th Dynasty of Egypt, ca. 2345-2181 BC, based on the inscription, the style, and the patina.27 This places the use of domesticated camels in Egypt at least as early as ca. 2200 BC. Other objects from Egypt include a limestone container, missing the lid, in the shape of a lying dromedary carrying a burden from a First Dynasty tomb at Abusir el-Meleq, 28 and a terra cotta tablet with a depiction of men riding and leading camels, dated to the Pre-Dynastic period.29

Container in the shape of a dromedary camel carrying a burden, Berlin Egyptian Museum. Credit: TM Kennedy

Container in the shape of a dromedary camel carrying a burden, Berlin Egyptian Museum. Credit: TM Kennedy

In Turkmenia, Altyn-depe, excavations revealed models of carts with camels yoked to them, in contrast to horses or cattle in other areas. The artifacts representing this utilization are 'terracotta models of wheeled carts drawn by Bactrian camels.' 30 'This type of utilization goes back to the earliest known period of two-humped camel domestication in the third millennium B.C.' 31 This is relevant not merely because it demonstrates the use of domesticated camels, but the early date of the stratigraphic context in which it was found is quite astonishing-3000 to 2600 BC.32 This discovery is reminiscent of the camel figurines with saddles found in a 2nd millennium BC context in Yemen, both of which show very early use of camels as pack animals and mounts.33

Finally, biological camel remains have been discovered at multiple sites in stratigraphic contexts from long before the Iron Age. Camel bone, dung, and woven camel hair dated to 2700-2500 BC have been discovered at Shahr-i Sokhta in Iran, preserved in jars.34 This “reinforces the suppositions that these are domestic stock and that the Bactrian was domesticated slightly earlier at the border of Turkmenistan and Iran.” 35 In addition to the findings in Iran and Turkmenia, discoveries of camel bones in a 3rd millennium BC context have been discovered at the Levantine sites of Arad and Jericho.36 At the sites of Umm an-Nar and Ras Ghanada in Abu Dhabi, fauna from a late 3rd millennium BC context included a large collection of camel remains, along with limited remains of domestic cattle, sheep, and goats.37 Woven camel-hair rope dated to the Third or early Fourth Dynasty was also found in Egypt at Umm es-Sawan.38 At the very least this suggests that the camel was used at these sites as a food source, but likely in some domesticated sense, since camels usually would have been kept outside of settlements and lived and died primarily in the steppe areas.39 Thus, finding camel bones or other biological artifacts in a settlement excavation is highly unlikely, and it follows that scribes, based in urban settlements, would not often mention the camel. This is a plausible rationale for the limited amounts of excavated camel remains and texts mentioning camels in any capacity.

Conclusion from the Data

As a result of the aforementioned data, many archaeologists regard the date for domestication of the camel to be sometime in the 3rd millennium BC. Scarre states that “both the dromedary (the one-humped camel of Arabia) and the Bactrian camel (the two-humped camel of Central Asia) had been domesticated since before 2000 BC.” 40 Saggs sees evidence for an early camel domestication date by “proto-Arabs” of the arid regions of the Arabian Peninsula.41 Macdonald’s research in southeast Arabia caused him to argue that based on archaeological remains, camels were probably first domesticated for milk, hair, leather, and meat, and subsequently travel across previously impassible regions in Arabia as early as the 3rd millennium BC.42 Heide regards evidence from multiple areas of the ancient Near East to demonstrate the presence of domesticated camels by at least the 3rd millennium BC.43 For those who adhere to a 9th century BC or even 12th century BC date of domestic camel use in the ancient Near East, archaeological and textual evidence must be either ignored or explained away. Bones, hairs, wall paintings, models, inscriptions, seals, documents, statues, and stelae from numerous archaeological sites all suggest the camel in use as a domestic animal in the ancient Near East as early as the 3rd millennium BC, and certainly by the Middle Bronze Age. The wide geographical and chronological distribution of findings related to camel domestication further strengthen the argument that the camel was domesticated far before the Iron Age, and with new excavations and analyses, additional evidence will likely reinforce this theory.

Endnotes:

[1] Redford, Donald B., 1992, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 277.

[2] Sapir-Hen, Lidar and Ben-Yosef, Erez. “The Introduction of Domestic Camels to the Southern Levant: Evidence from the Aravah Valley.” Tel Aviv 40 (2013): 277-285.

[3] Finkelstein, Israel and Silberman, Neil Asher, 2001, The Bible Unearthed, Free Press: New York, 37.

[4] Drews, Robert, 1993, The End of the Bronze Age, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 165.

[5] Albright, W.F., 1951, The Archaeology of Palestine, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, 207.

[6] Ibid, 206.

[7] Rosen, Steven and Saidel, Benjamin. “The Camel and the Tent: An Exploration of Technological Change Among Early Pastoralists.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 69/1 (2010): 63. Rosen and Saidel also note evidence that points to 3rd millennium BC camel domestication in Arabia (cf. 2010: 74-76).

[8] Although the date for the setting of Job is debatable, it is plausible to place it in a Middle Bronze context similar to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. There are several similarities in the texts, such as life over 140 years, wealth measured in livestock, the patriarch as the priest of the family, and no mention of the nation Israel or the Mosaic Law.

[9] In Egypt, Abraham is given a gift of servants and several types of domesticated animals, including “sheep and oxen and donkeys…and female donkeys and camels” (Genesis 12:16) and later one of his servants “made the camels kneel down outside the city by the well of water at evening time” (Genesis 24:11). Jacob used camels for transportation, putting “his children and his wives upon camels” (Genesis 31:17) and to own “milking camels and their colts” (Genesis 32:15). The camels in Exodus were part of the various domesticated animals of the Egyptians (Exodus 9:3), while in Judges camels are domesticated beasts of the Midianites and Amalekites (7:12). The book of Job claims that the protagonist possessed camels in the context of other domesticated animals (Job 1:3).

[10] Millard, A.R, 1980, “Methods of Studying the Patriarchal Narratives as Ancient Texts,” Essays on the Patriarchal Narratives, ed. A.R. Millard, D.J. Wiseman, InterVarsity Press, Leichester, pp.43-56, 50.

[11] Potts, Daniel, 2004, “Bactrian Camels and Bactrian-Dromedary Hybrids,” (off-site link), based on Potts, Daniel, 2004, “Camel hybridization and the role of Camelus bactrianus in the Ancient Near East,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 47:143-165.

[12] Oppenheim, Max von Freiherr, 1931, Der Tell Halaf: Eine neue Kultur im ältesten Mesopotamien. F.A. Brockhaus, Leipzig, 140.

[13] Ripinsky, Michael, 1983, “Camel Ancestry and Domestication in Egypt and the Sahara,” Archaeology 36:21-27, 27.

[14] Gerster, Georg, 1961, Sinai, Darmstadt, Germany, 62.

[15] Younker, Randall W., 1997, “Bronze Age Camel Petroglyphs In The Wadi Nasib, Sinai,” Near East Archaeological Society Bulletin, 42:47-54, 49.

[16] Ibid, 49.

[17] Gardiner, A. H., and Peet, T. E., 1955, The Inscriptions of Sinai. Vol 2. Egypt Exploration Society, London, 76.

[18] Naveh, Joseph, 1982 Early History of the Alphabet: an Introduction to West Semitic Epigraphy and Paleography, The Magnes Press, Jerusalem, 26.

[19] Younker, 1997, Near East Archaeological Society Bulletin 42, 49.

[20] Barnett, Richard D., 1985, “Lachish, Ashkelon and the Camel: A Discussion of Its Use in Southern Palestine” in: J.N. Tubb, ed. Palestine in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Papers in Honor to Olga Tuffnell, London, Institute of Archaeology, pp. 16-30, 16.

[21] MacDonald, 1995, “North Arabia in the First Millennium BCE,” 1363.

[22] Black, Jeremy; George, Andrew; Postgate, Nicholas, eds., 2000, A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 89.

[23] Potts, Daniel, 2004, “Bactrian Camels and Bactrian-Dromedary Hybrids,” (off-site linke), last accessed Feb. 2014. Based on Potts, Daniel, 2004, “Camel hybridization and the role of Camelus bactrianus in the Ancient Near East,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 47:143-165.

[24] Archer, Gleason, 1970, “Old Testament History and Recent Archeology from Abraham to Moses” Bibliotheca Sacra 127:505 pp. 3-25, 17.

[25] Davis, John J., 1986 “The Camel in Biblical Narratives,” in A Tribute to Gleason Archer: Essays on the Old Testament, Chicago, Moody Press: pp.141-150, 145.

[26] Wiseman, Donald J., 1959, “Ration Lists from Alalakh VII,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 13:19-33, 29.

[27] Ripinsky, 1985, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 71, 138.

[28] Ripinsky, Michael, 1985, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 71, 136.

[29] Free, Joseph P., 1944, “Abraham’s Camels,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 3:187-193, 189-190.

[30] Kohl, P. L., 1992 “Central Asian (Western Turkestan): Neolithic to the Early Iron Age.” in Ehrich, R. W., ed., 1992, Chronologies in Old World Archaeology, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London: pp. 179-195, 186.

[31] Bulliet, Richard W., 1990, The Camel and the Wheel. Columbia University Press, 183.

[32] Renfrew, Colin, 1987, Archaeology and Language, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, 201.

[33] Meyers, Eric M., ed., 1997, 407.

[34] Wapnish, Paula, 1981, “Camel Caravans and Camel Pastoralists at Tell Jemmeh,” Journal of the Ancient Near East Society, 13:101-121, 104-105.

[35] Meyers, Eric M., ed., 1997, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 407.

[36] Ibid, 407.

[37] Hesse, Brian, 1995, “Animal Husbandry and Human Diet in the Ancient Near East” in J. M. Sasson ed., Civilizations of the Near East, Vol. 1, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, pp. 205-218, 217.

[38] Ripinsky, Michael, 1985, “The Camel in Dynastic Egypt,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 71:134-141, 138.

[39] Kramer, Carol, 1977, “Pots and People,” in Levine, L. D. and Young, T. C. Mountains and lowlands: Essays in the archaeology of greater Mesopotamia; Bibliotheca Mesopotamica. Vol. 7, Udena Publications, Malibu: pp. 91-112, 100.

[40] Scarre, Chris,1993, Smithsonian Timelines of the Ancient World, DK Adult, 176.

[41] Saggs, H.W.F., 1989, Civilization Before Greece and Rome, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 19.

[42] MacDonald, M. C. A., 1995, “North Arabia in the First Millennium BCE.” in J. M. Sasson ed., Civilizations of the Near East, Vol. 2, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, pp. 1355-1369, 1357.

[43] Heide, K. M. “The Domestication of the Camel: Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible.” Ugarit-Forschungen 42 (2010): 331-384. (Off-site link.)

Bibliography:

Albright, W.F. 1951. The Archaeology of Palestine. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Archer, Gleason. 1970. “Old Testament History and Recent Archeology from Abraham to Moses.” Bibliotheca Sacra 127:505 (1970): 3-25.

Barnett, Richard D. 1985. “Lachish, Ashkelon and the Camel: A Discussion of Its Use in Southern Palestine.” In J.N. Tubb, ed., Palestine in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Papers in Honor to Olga Tuffnell. London, Institute of Archaeology, 16-30.

Black, Jeremy; George, Andrew; Postgate, Nicholas, eds. 2000. A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden.

Bulliet, Richard W. 1990. The Camel and the Wheel. Columbia University Press.

Caesar, Stephen. 2000. “Patriarchal Wealth and Early Domestication of the Camel.” Bible and Spade 13:3 (200): 77-79.

Collon, Dominque. 2000. “L’animal dans les échanges et les relations diplomatiques.” In Les animaux et les hommes dans le monde syro-mésopotamien aux époques historiques, Topoi Supplement 2, Lyon: 125-140.

Davis, John J. 1986. “The Camel in Biblical Narratives.” In A Tribute to Gleason Archer: Essays on the Old Testament. Chicago, Moody Press: 141-150.

Drews, Robert. 1993. The End of the Bronze Age. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Finkelstein, Israel and Silberman, Neil Asher. 2001. The Bible Unearthed. Free Press: New York.

Free, Joseph P. 1944. “Abraham’s Camels.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 3: 187-193.

Gardiner, A.H. and Peet, T.E. 1955. The Inscriptions of Sinai, Vol 2. Egypt Exploration Society, London.

Gerster, Georg. 1961. Sinai. Darmstadt, Germany.

Heide, K.M. 2010. “The Domestication of the Camel: Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible.” Ugarit-Forschungen 42 (2010): 331-384. (Off-site link.)

Hesse, Brian. 1995. “Animal Husbandry and Human Diet in the Ancient Near East” in J.M. Sasson ed., Civilizations of the Near East, Vol. 1. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York: 205-218.

Kramer, Carol. 1977. “Pots and People,” in Levine, L.D. and Young, T.C. Mountains and lowlands: Essays in the archaeology of greater Mesopotamia. Bibliotheca Mesopotamica. Vol. 7. Udena Publications, Malibu: 91-112.

Kohl, P.L. 1992. “Central Asian (Western Turkestan): Neolithic to the Early Iron Age,” in Ehrich, R.W., ed., 1992, Chronologies in Old World Archaeology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London: 179-195.

MacDonald, M.C.A. 1995. “North Arabia in the First Millennium BCE.” in J.M. Sasson ed., Civilizations of the Near East, Vol. 2. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York: 1355-1369.

Meyers, Eric M., ed. 1997. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Millard, A.R. 1980. “Methods of Studying the Patriarchal Narratives as Ancient Texts.” Essays on the Patriarchal Narratives, ed. A.R. Millard, D.J. Wiseman. InterVarsity Press, Leichester: 43-56.

Naveh, Joseph. 1982. Early History of the Alphabet: an Introduction to West Semitic Epigraphy and Paleography. The Magnes Press, Jerusalem.

Oppenheim, Max von Freiherr. 1931. Der Tell Halaf: Eine neue Kultur im ältesten Mesopotamien. F.A. Brockhaus, Leipzig.

Potts, Daniel. 2004. “Bactrian Camels and Bactrian-Dromedary Hybrids” (off-site link), last accessed Feb. 2014. Based on: Potts, Daniel, 2004, “Camel hybridization and the role of Camelus bactrianus in the Ancient Near East.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 47: 143-165.

Redford, Donald B. 1992. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Renfrew, Colin. 1987. Archaeology and Language. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Ripinsky, Michael. 1983. “Camel Ancestry and Domestication in Egypt and the Sahara.” Archaeology 36: 21-27.

- “The Camel in Dynastic Egypt.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 71: 134-141.

Rosen, Steven and Saidel, Benjamin. “The Camel and the Tent: An Exploration of Technological Change Among Early Pastoralists.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 69/1 (2010): 63-77.

Saggs, H.W.F. 1989. Civilization Before Greece and Rome. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Sapir-Hen, Lidar and Ben-Yosef, Erez. 2013. “The Introduction of Domestic Camels to the Southern Levant: Evidence from the Aravah Valley.” Tel Aviv 40 (2013): 277-285.

Scarre, Chris. 1993. Smithsonian Timelines of the Ancient World. DK Adult.

Shanks, Hershel, ed. 1995. “WorldWide: Assyria (Iraq).” Biblical Archaeology Review 21: 02.

Wapnish, Paula. 1981. “Camel Caravans and Camel Pastoralists at Tell Jemmeh.” Journal of the Ancient Near East Society 13: 101-121.

Wiseman, Donald J. 1959. “Ration Lists from Alalakh VII.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 13: 19-33.

Younker, Randall W. 1997. “Bronze Age Camel Petroglyphs In The Wadi Nasib, Sinai.” Near East Archaeological Society Bulletin 42: 47-54.