Where We’ve Been

Except for my last article on the ABR website, “A Closer Look: Daniel 8:14 Re-examined,” most of the recent articles in the series have given special attention to various aspects involved in interpreting Daniel 9:25. Here are links to those articles, oldest first:

The Seraiah Assumption and the Decree of Daniel 9:25

The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping Up Some Loose Ends

Did Ezra Come to Jerusalem in 457 BC?

The Going Forth of Artaxerxes’ Decree Part 1

The Going Forth of Artaxerxes’ Decree Part 2

Of particular interest at this special time of year is my article on “Pinpointing the Date of Christ’s Birth.” With over 27,000 hits on the ABR website, it is humbling to see how popular it has been, indicating it has been well received and shared with others. If you have never read it, may I encourage you to do so? Its conclusions were arrived at independently of the main research on Daniel, but are consistent with it.

Daniel’s Seventy Weeks were Seventy Sabbatical Year Cycles

The present study moves beyond Daniel 9:25 to consider verses 26 and 27, which deal with things that take place during and after Daniel’s 69th week. We begin by first affirming a key finding of this study, discussed in Part 1 of “The Going Forth of Artaxerxes’ Decree.” It presented the case that the “weeks” of Daniel 9:24–27 should be understood as sabbatical year cycles following a fixed schedule, not arbitrary periods of seven years. Since sabbatical years were always counted from the first of Tishri, if the “sevens” of Daniel 9 are sabbatical year cycles, their restart in the postexilic period must be counted from that date in some year. That year was determined from the study in “Did Ezra Come to Jerusalem in 457 BC?,” which indicated that Artaxerxes’ seventh regnal year was 458–457 BC, and the decree promulgated during it was the only one that can be connected with both the rebuilding of Jerusalem and its restoration. Some teach that the rebuilding of Jerusalem’s walls by Nehemiah in 444 BC marked this decree, but these studies have shown no decree was issued that year; the letters (Heb. 'iggereth) issued to facilitate Nehemiah’s border crossings and purchase of building materials (Neh 2:7–8) did not rise to the level of an imperial decree (Heb. ta'am), being merely a means to implement a ta'am which had already been issued, but never effectively acted on. The official permission to undertake the city’s rebuilding traced back to the 457 BC decree, and the fact that it still had not been done, over a decade after it was authorized, must be the reason why Nehemiah was so upset to learn the walls still remained unrepaired (all Scriptures from the NASB):

Now it happened in the month Chislev, in the twentieth year, while I was in Susa the capitol, that Hanani, one of my brothers, and some men from Judah came; and I asked them concerning the Jews who had escaped and had survived the captivity, and about Jerusalem. They said to me, “The remnant there in the province who survived the captivity are in great distress and reproach, and the wall of Jerusalem is broken down and its gates are burned with fire.” When I heard these words, I sat down and wept and mourned for days; and I was fasting and praying before the God of heaven (Neh 1:1–4).

Nehemiah’s wall repair efforts were thus a delayed fulfillment of the rebuilding aspect of the 457 BC decree. The other aspect, the restoration referenced in Daniel 9:25, fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah 1:21–26:

How the faithful city has become a harlot,

She who was full of justice!

Righteousness once lodged in her,

But now murderers…

Therefore the Lord God of hosts,

The Mighty One of Israel, declares,

“Ah, I will be relieved of My adversaries

And avenge Myself on My foes.

I will also turn My hand against you,

And will smelt away your dross as with lye

And will remove all your alloy.

Then I will restore your judges as at the first,

And your counselors as at the beginning;

After that you will be called the city of righteousness,

A faithful city.”

This restoration was essentially a spiritual one, with Ezra serving as God’s agent to accomplish it. He did this by bringing with him a full complement of Levites, intensively teaching the people the precepts of the Law, and insisting that they be followed to the letter. Therefore, it was after Ezra’s arrival in 457 BC that the sabbatical year cycles stipulated by the Law were initiated, not after Nehemiah’s later construction-focused arrival in 444. We cannot use 444 BC as the anchor point for the start of the Seventy Weeks count.

That analysis, when joined with the evidence that Ezra’s return to the Land took place in the summer of 457 BC, led to the conclusion that the count of Daniel’s Seventy Weeks—seventy sabbatical year cycles—began on Tishri 1, 457 BC. This was the earliest possible date when it could be said that Jerusalem had been spiritually restored and a sabbatical cycle count could have been initiated. That this is the correct date is further indicated by the reading of the Law by Ezra on Tishri 1, 444 BC (Neh 8:1–2, cf. Dt 31:10–12), which signified that the year 444–443 BC was a sabbatical year. Taking the seven-year sabbatical cycle pattern back in time from that year marks 457–456 BC as the first year of a sabbatical cycle, corroborating the independently-determined date of Ezra’s arrival. This correlates perfectly with the sabbatical year pattern developed by Benedict Zuckermann. The pattern proposed by Ben Zion Wacholder is incompatible with this information from Scripture, as discussed in detail in Part 2 of “The Going Forth of Artaxerxes’ Decree.” In this way the words of Daniel 9:25 were fulfilled:

So you are to know and discern that from the issuing of a decree to restore and rebuild Jerusalem until Messiah the Prince there will be seven weeks and sixty-two weeks; it will be built again, with plaza and moat, even in times of distress.

Checking the Math

The word “until” was emphasized above because it is critically important to a correct understanding of verses 26 and 27. Daniel 9:25 says that from the issuing of the proper decree until—up to the time of—the “manifestation” (Gk. phaneróō, Jn 1:31) of the Anointed One, 69 sabbatical year cycles, 483 years total, would pass first. The little word “until” tells us the seventh year of the 69th sabbatical year cycle would come to a complete end before the Messiah would be revealed. This might shock people accustomed to thinking Daniel’s 69th week ended with the Crucifixion, but the text of Scripture is actually quite clear. It takes priority over the errors of prophecy teachers who have overlooked it.

So to review: this study determined that 457–456 BC, Tishri through Elul, was the first year of the first sabbatical cycle after the decree of Artaxerxes in his seventh year sent Ezra to Jerusalem. That same decree also authorized the rebuilding of the infrastructure—the walls and plazas—of the city, work which, to Nehemiah’s heartbreak at Hanani’s bad report, was delayed by opposition until Nehemiah decided to act on that decree and arrived in 444 BC. The first sabbatical year of the postexilic period was 451–450 BC. The second sabbatical year was seven years after that, which kicked off on Tishri 1, 444 BC with the reading of the Law by Ezra (Neh 8:1–2). If we plug these years into the table at http://www.pickle-publishing.com/papers/sabbatical-years-table.htm, we find they match the pattern of Zuckermann. That of Wacholder, offset six months later, simply will not work with Scripture. When we carefully analyze Scripture itself and make it the starting point for everything that follows—not unproved church traditions of a 3/2 BC date for Christ’s birth, denominational distinctives, or complex theological arguments by those with a vested interest in a specific answer—we find that its plain sense and the ancient historical records are entirely congruent.

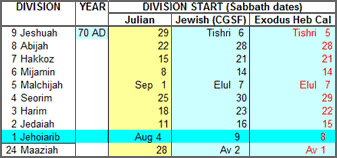

Using Zuckermann’s pattern, then, when we count 69 sabbatical year cycles forward from 457 BC, we find the final year of those 69 weeks of years spans Tishri 1 (September 30), AD 26 through Elul 29 (September 19), AD 27. Therefore, the prophecy of Daniel’s 70 Weeks informs us that the Messiah could not be manifested until Tishri 1, the Feast of Trumpets, AD 27 at the earliest.

The Underlying Unity of the Seventy Weeks

While this study did not pay much attention to Daniel 9:24 because it does little more than introduce the passage, one overarching thing it says needs to be kept in mind as we read the rest of the prophecy: “Seventy weeks have been decreed for your people and your holy city.” These seventy weeks thus have primary reference to God’s dealings with the Jews, not with the world or the Church, except insofar as Jewish affairs impact them. Saying this has nothing to do with any attempt to defend an overarching dispensationalist view, but only with faithful adherence to the text and context of Daniel 9:24–27.

This self-declared restriction on the scope of the prophecy is another reason for regarding the “weeks” as Jew-specific sabbatical year cycles. The focus on the Jews seen in 9:24 provides a common framework for interpreting the following three verses. And their scope can be narrowed down still further, for their direct connection with Jerusalem means they apply particularly to times when the Jews fully controlled their holy city. This is further evidence we are dealing with sabbatical year cycles, which are inseparable from the combination of (1) self-government of the Jews, by the Jews, from Jerusalem; (2), a fully-functioning Temple-based sacrificial system; and (3), the pursuit of agriculture within the Holy Land that includes land-rests every seven years. These deductions follow from the fact that the reinstitution of sabbatical year counts after the exile did not begin with Zerubbabel’s limited return to the Land, but only after both the rebuilt Temple and Ezra’s resumption of Torah adherence were in place. For these reasons we cannot say the Jews’ limited return to the Land seen so far in our day has restarted sabbatical year counting, which was interrupted when the arrival of the Lamb of God set aside the sacrificial system centered on the Temple. It will not restart until the Third Temple is built and full Torah observance reinstituted. Until then, the sabbatical cycle clock has been paused. The Seventieth Week has not yet begun.

Hasel and the Significance of the Hebrew Masculine Plural

In this connection it is worth noting a study by Seventh-day Adventist theologian Gerhard Hasel, “The Hebrew Masculine Plural for ‘Weeks’ in the Expression ‘Seventy Weeks’ in Daniel 9:24” (PDF at https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2088&context=auss). His thesis is that the use of the Hebrew masculine plural form of sabu’a in Daniel 9, markedly contrasting with the normally-used feminine plural ending (where the word generally refers to an ordinary seven-day week), signifies an underlying unity of the weeks. He claims this unity consists in their linear, gap-free sequence, such that the 70th week followed immediately after the 69th. In this way he finds support for the SDA contention that the 70th week was the years AD 28–34.

It must be said that Hasel’s grammatical analysis is solid and cogent. However, what kind of unity is intended is a separate issue. Must it consist in a consecutive chronological unity of the seven, 62 and one weeks as Hasel proposes, forcing us to start the 70th week as soon as the 69th week ends, or is it a unity of a different sort? If we remove the SDA doctrinal constraint which influences Hasel’s interpretation, another solution presents itself: the unity could consist in each “week” being a sabbatical year cycle. The use of the masculine plural form sabu’im in Daniel is, as many have noted, unique in the Old Testament. My suggestion is that it is unique to Daniel because it is one of the methods by which God “sealed” the book to make the prophecy difficult to decipher.

On page 113 Hasel notes:

It has become rather certain that such plurals are not employed in an arbitrary fashion, but that they serve particular and specific purposes. It is typical of nouns with plural endings in -im and -ot that the plural of -im is to be understood as a plural of quantity or a plural of groups, whereas -ot indicates an entity or grouping which is made up of individual parts. I hold that this is true of sabu’a just as it is known to be true concerning other nouns (emphasis mine).

Since a sabbatical year cycle is a group of seven years, we can immediately see how the masculine plural ending could refer to them in Daniel 9. The unity Hasel calls for us to recognize, therefore, is probably not of chronologically consecutive periods of seven, 62 and one “weeks,” but of a plurality of sabbatical year cycles.

Sir Robert Anderson and His 360-Day “Prophetic Year”

Now we turn to a past effort to make sense of Daniel 9:24–27, that of Sir Robert Anderson. His views were set forth in The Coming Prince in 1895, so they’ve been around for a long time. Anderson’s book was published following the popularizing of dispensationalism by John Nelson Darby in the first half of the nineteenth century, and was geared to supporting its key points in eschatology. As described by Bob Pickle at http://www.pickle-publishing.com/papers/sir-robert-anderson.htm, they included the ideas that “the first 69 weeks of Daniel 9 began with the 20th year of Artaxerxes and ended about the time of the crucifixion of Christ”; “the 70th week is yet future”; and “the prince that confirms the covenant in Daniel 9:27 is a future antichrist who will stop the sacrifices in a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem.” Pickle summarizes Anderson’s theory, the essentials of which are set forth at http://www.swartzentrover.com/cotor/E-Books/christ/Anderson/Prince/TCP_10.htm:

Anderson, like all expositors, considered the 69 weeks (483 days) to really be 483 years. He then multiplied these 483 years by what he called a “prophetic year,” a 360-day year. This gave him a total of 173,880 days, and effectively shortened the time period down to about 476 actual years, since a 360-day year is shy of the true solar year by over 5 days.

Although there are places in Scripture where a year appears to be defined as 360 days, we shall see that Daniel 9:24–27 is not one of them. But Anderson needed a strategy to make his Darby-determined starting point for counting the weeks—the 20th year of Artaxerxes Longimanus—fit together with a seemingly reasonable year for the “cutting off” of the Messiah. It required viewing the year as only 360 days long for the entire 483-year period. Toward this end he devoted his entire Chapter 6 in defense of this thesis; see http://www.swartzentrover.com/cotor/E-Books/christ/Anderson/Prince/TCP_06.htm. Anderson draws his reader’s attention to the following passages:

Now this seventieth week is admittedly a period of seven years, and half of this period is three times described as “a time, times, and half a time,” or “the dividing of a time;” (Daniel 7:25; 12:7; Revelation 12:14) twice as forty-two months; (Revelation 11:2; 13:5) and twice as 1,260 days. (Revelation 11:3; 12:6) But 1,260 days are exactly equal to forty-two months of thirty days, or three and a half years of 360 days, whereas three and a half Julian years contain 1,278 days. It follows therefore that the prophetic year is not the Julian year, but the ancient year of 360 days.

Anderson’s analysis focuses on the 70th week, where he shows that passages in Daniel and Revelation appear to use a year of 360 days. But then, he extrapolates from this observation to the other 69 weeks. Is this valid? Here are the Scriptures he cited, with some notes in brackets to keep us grounded in the context:

Dan 7:25 He [the Antichrist] will speak out against the Most High and wear down the saints of the Highest One, and he will intend to make alterations in times and in law; and they will be given into his hand for a time, times, and half a time.

Dan 12:7 I heard the man dressed in linen, who was above the waters of the river, as he raised his right hand and his left toward heaven, and swore by Him who lives forever that it would be for a time, times, and half a time; and as soon as they [the Antichrist and his forces] finish shattering the power of the holy people, all these events will be completed.

Rev 11:2 Leave out the court which is outside the temple and do not measure it, for it has been given to the nations [which follow the Antichrist]; and they will tread under foot the holy city for forty-two months.

Rev 11.3 And I will grant authority to my two witnesses [against the Antichrist], and they will prophesy for twelve hundred and sixty days, clothed in sackcloth.

Rev 12:6 Then the woman [signifying the alert Jews] fled [from the Antichrist] into the wilderness where she had a place prepared by God, so that there she would be nourished for one thousand two hundred and sixty days.

Rev 12:14 But the two wings of the great eagle were given to the woman [the alert Jews], so that she could fly into the wilderness to her place, where she was nourished for a time and times and half a time, from the presence of the serpent [signifying the Antichrist].

Rev 13.5 There was given to him [the Antichrist] a mouth speaking arrogant words and blasphemies, and authority to act for forty-two months was given to him.

These passages show that Anderson’s 360-day “prophetic year” only applies to the second half of Daniel’s 70th week, during which the end-time Antichrist cracks down on the Jews and makes “alterations in times and law” (Dan 7:25)—which may imply he changes the calendar, possibly under Islamic influence, to a purely lunar-based one of 360 days. At any rate, nowhere in Scripture is a 360-day year applied to the other 69 weeks, or even to the first half of the 70th. We thus have no biblical basis for assuming the first 483 years of Daniel’s weeks followed anything but an ordinary calendar governed by a 365-day solar cycle. Anderson, however, began with Darby’s determination that the count of the 70 weeks began in Artaxerxes’ 20th year, then extrapolated a 360-day “prophetic year” to the entire time spanned by the first 69 sabbatical year cycles. He did this in order to arrive at a date for the Crucifixion that was in the expected ballpark. This strategy of assuming what had to be proved puts in grave doubt the validity of anchoring the weeks of Daniel 9:24–27 on the 20th year of Artaxerxes, completely apart from its problems already pointed out. As other articles in The Daniel 9:24–27 Project have explained (see in particular the discussion in the article on the Seraiah Assumption under the heading “Artaxerxes’ Seventh Year Decree Covered Both City and Temple”), the decree in Artaxerxes’ seventh year, 457 BC, is far preferable, and allows us to use ordinary solar years for adding up the weeks. When we join to that the fact that the 69th sabbatical year cycle had to conclude before both the Messiah’s manifestation and His crucifixion (remember the word “until”), we find Anderson misunderstood Scripture. But when we follow the approach taken in this study, every year up to the second half of the 70th week, when Scripture notes that the Antichrist makes “alterations in times,” is an ordinary calendar year.

The Interpretation of Harold Hoehner

In this regard we should also mention the analysis of Daniel 9 presented by Harold Hoehner of Dallas Theological Seminary. Cut from the same theological cloth as Anderson’s work but reflecting certain improvements—in particular, he moves Anderson’s 445 BC date for Nehemiah completing the wall to 444 BC, so the year of the Crucifixion moves from AD 32 to 33—his calculations in Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ likewise assume a 360-day “prophetic year” and share its weaknesses. Due in large part to the effective way his view has been promoted by dispensational teachers in books, conferences, radio and television, it is the paradigm chronology of Christ’s life adopted by a large portion of the evangelical world.

But may I encourage my readers not to equate commercial success with biblical accuracy? In the end, every teacher must be held accountable to the straightforward sense of the Word of God. The aim of this study has always been to go first to the Bible itself for answers rather than human teachers, regardless of their popularity or academic credentials. We must judge their teachings by the text of Scripture, not by how well they support favored theological perspectives. That is why I have drawn insights from people from a variety of backgrounds in this study. I think that because, like Anderson, Hoehner assumes Daniel’s count of the 70 "weeks" began in the 20th year of Artaxerxes and similarly requires positing a 360-day “prophetic year” for the entire period (not just the second half of the 70th "week), this aspect of his chronology should be rejected. His view that the 70th "week" is still future is not affected by this, though, and can be evaluated on its own merits.

An additional criticism against Hoehner’s view has to do with his AD 33 date for the Crucifixion. He did improve upon Anderson’s AD 32, when the Passover is impossible to reconcile with the gospels’ requirement that the Lord rose on the first day of the week (our Sunday). However, by choosing AD 33 rather than AD 30 which also puts the Resurrection on a Sunday, he had to make an unjustified assumption: that the Lord’s public ministry lasted for 3-1/2 years. That this is an assumption is seen in the fact that John’s gospel mentions only three Passovers by name (Jn 2:13, 6:4, and 11:55). This yields a public ministry of two years sandwiched between the first and last Passover, plus about half a year covering His baptism, temptation in the wilderness, and calling His disciples. (I discussed this further in my “Fifteenth Year of Tiberius” article.) The supposed fourth Passover, needed to stretch Christ’s ministry to 3-1/2 years and end in AD 33, was an unnamed “feast of the Jews” in John 5:1. Since the other three Passovers were consistently identified as such, if the feast in 5:1 was also a Passover we would expect it would have been similarly identified. The other two pilgrimage festivals celebrated in Jerusalem were Shavuot (Weeks) and Sukkot (Tabernacles). No one can say for certain what feast 5:1 refers to; my own suspicion is that it is Shavuot, the most minor of the pilgrimage festivals, lasting but a single day rather than a full week like the other two. It appears the only reason some regard it as a Passover is because it provides the extra time needed to push the Crucifixion into AD 33, which some unfortunately view as a non-negotiable date that must be defended at all costs.

Therefore, if Christ’s baptism was on or just after Tishri 1, AD 27 as this study indicates, the first Passover was that of AD 28, the second in AD 29, and the last—when our Lord was crucified—in AD 30. An AD 33 date for the Crucifixion also cannot be reconciled with the salvation of the Apostle Paul 14 years before the death of Herod Antipas, known from solidly documented history to have taken place in 44 AD. That analysis was given in “How Acts and Galatians Indicate the Date of the Crucifixion.” It shows that Paul was probably saved in AD 30 or 31, ruling out an AD 33 Crucifixion.

Those who enjoy technical math connected with calendars (I do not!) may find the discussion by Bob Pickle at http://www.pickle-publishing.com/papers/harold-hoehner-70-weeks.htm further illuminates the problems posed by Hoehner’s approach. The biggest difficulty with the overall solution Pickle proposes is that it fails to account for the interregnum between the 69th and 70th weeks of Daniel, to be discussed below.

As an aside, I believe that the original year at Creation was 360 days long, with the solar and lunar cycles perfectly synchronized. This explains why the earliest Sumerian civilization after the Flood devised the base-60 standards of a 360-degree circle, 60 seconds to a minute, and 60 minutes to an hour. But I hypothesize that something happened during the “days of Peleg,” discussed on the ABR website (see https://biblearchaeology.org/research/flood/2887-making-sense-of-the-days-of-peleg and https://biblearchaeology.org/research/flood/2798-revisiting-the-peleg-event), when a cosmic impact threw the original precise balance between the solar and lunar cycles out of kilter, speeding up the Earth’s rotation and yielding its present 365-day solar year (faster rotation of the Earth would squeeze more days into the same absolute time span). That impact’s side effects included suddenly shifting the post-Flood mammoth herds, at literally breath-taking speed (remains indicate they were buried in wind-blown loess and died of asphyxiation) into the deep freeze of the high Arctic, wiping out the Clovis Paleoindian culture, and leaving behind an iridium-rich, radioactive “black mat” in the geological layers. But we are not addressing that story today. Those interested in more information can check the links.

To wrap up this section, I believe the straightforward sense of the passage allows us to say it exhibits an underlying unity of the “weeks” that lies in their being sabbatical year cycles. They are also unified in that the years, up to the last half of the 70th week, are ordinary 365-day solar years.

The Divisions in the Seventy Weeks

Now we turn to look at the nature of the divisions seen in the prophecy of the Seventy Weeks—the periods of seven, 62, and one week.

The First Seven Weeks

Some theologians point to the atnah disjunctive accent in the Masoretic text of Daniel 9:25 as reason to disconnect the coming of some “anointed prince” after seven weeks from the 62 weeks of building the city that follows. In his July 3, 2010 blog entry, Dr. Michael Heiser explains:

In Dan 9:25 the Masoretic tradition places what is called a disjunctive accent (atnah) between the words for “seven sevens / weeks” and “sixty-two sevens.” A disjunctive accent served to separate items on either side of the accent. That means the Masoretes saw a break (a disjunction) between the 7 weeks and the following 62. This in turn means that the “anointed one” comes at the end of the seven weeks, before the other 62 occur.

Less technically, the atnah functions like a comma or semicolon in English, introducing a separation in the flow of a sentence. Heiser observes that the ESV, RSV and NRSV renderings follow the Masoretic punctuation, implying that a messianic figure comes on the scene at the end of the first seven weeks. By this view the masiach could not be Jesus. On the other hand, he notes that the NIV, NLT and KJV ignore the Masoretic disjunctive accents “for one reason or another,” so in those translations the “anointed one” is manifested after the combined total of 69 weeks, thereby identifying him with Christ. J. Paul Tanner has also pointed out (“Is Daniel’s Seventy-Weeks Prophecy Messianic? Part 2,” Bibliotheca Sacra, July-September 2009, p. 326) that the early Greek translations of Daniel which preceded the Masoretic text—the Septuagint, Theodotion, Symmachus and the Peshitta—as well as the Latin Vulgate, likewise do not separate the seven and 62 weeks, but view them as a contiguous 69-week period between the decree and the coming of the Messiah, thus providing ancient support for ignoring the atnah.

What are we to make of all this? If we get down to the basics, keying on the atnah to interpret the verse puts a disproportionate emphasis on using uninspired, late-added punctuation of suspect theological impartiality (it was tied to rabbinical oral tradition) to determine the meaning of the text. Moreover, evaluating the disjunctive accent cannot be done without also considering what is supposed to have occurred on either side of it. It involves having an unclear messianic figure come on the scene 49 years after the counting of “weeks” begins, whenever that was, followed by 434 years during which Jerusalem was supposedly rebuilt. The available options are unsatisfying, with Antiochus Epiphanes and the martyred high priest Onias III often proposed as the messianic figure. But Don Preston, at https://donkpreston.com/daniels-seventy-week-prophecy-three-messiahs-three-princes-3/, convincingly argues that Daniel 9:24 demands a Messiah who could make atonement, take away sin, and bring in everlasting righteousness, and thus had to be a fully legitimate high priest (Heb 2:17). Preston’s analysis shows that neither Antiochus Epiphanes nor Onias III qualify; only Jesus of Nazareth, a high priest “after the order of Melchizedek” (Heb 5:6, 10), fulfills the requirements.

As for the other side of the break, how reasonable is it to suppose that it took 434 years to rebuild Jerusalem? Daniel 9:25 describes that rebuilding as entailing the completion of “plaza (Heb. rĕchob) and moat (charuwts)” (Dan 9:25). These relate to infrastructure construction and repairing the walls (which have defensive moats—trenches—at their bases) that delineate the city limits, not the construction of individual homes and businesses. These infrastructure matters are the things which, if we stick the atnah into Daniel 9:25, supposedly took all of 434 years to complete! This is nonsense.

A better alternative is to ignore the atnah, with its resultant dubious “messiah” and extraordinary duration of city rebuilding, and seek another explanation why the first 49 years are mentioned separately from the 434 that follow them. Some interpreters who rightly regard the Messiah of Daniel 9:25 as Jesus have suggested that the first seven weeks of Daniel 9:25 referred to city rebuilding. However, the only clear time indicator in either Scripture or extrabiblical history bearing on the rebuilding is the completion of the wall repairs by Nehemiah in 444 BC, just 13 years after Ezra’s arrival (see the discussion in Part 1 of the Artaxerxes article). If it actually took 49 years there should be some relatively obvious event to validate it, but to my knowledge neither the Bible nor secular history provides one, whether the count is started in 457 or 444 BC.

On the other hand, since the walls and gates which Nehemiah repaired served to define the city limits, it is easy to see repairing them as equivalent to rebuilding the city. If finishing those repairs during the “times of distress” (Dan 9:25), when the “people of the land” under Sanballat, Tobiah, and Geshem the Arab attempted to sidetrack the work (Neh 2–6), was not the objective endpoint of the rebuilding, then what was it? Consider also that, when we read the account of the wall-completion celebration in Nehemiah 8:1, we are told the people gathered at the square (rĕchob) in front of the Water Gate. This and the account in Nehemiah 8:16, where the Feast of Booths was celebrated in two squares of the city, give us evidence that the plazas/squares had already been rebuilt by that time. As for other construction, all cities continually add homes and businesses and make infrastructure improvements as the years pass, so it seems impossible to use such construction to say at a certain point, “the city’s finished!” The walls which define the city limits, however, constitute a clear-cut, objective criterion of city completion. So it appears that saying it took 49 years to rebuild the city is purely arbitrary.

The Seven Weeks as a Jubilee Cycle

So, what do the first 49 years signify? My view is that the Lord directed Gabriel to set off the first seven weeks from the 62 that followed to mark the completion of a Jubilee of seven sabbatical cycles. In this way he provided us with a hint that the remaining 62 and one final week are also to be interpreted as sabbatical year cycles. Since a Jubilee merges seamlessly into the sabbatical year that follows it, yet at the same time can be regarded as a unit on its own, the “seven weeks and sixty-two weeks” should be linked seamlessly together to fill the period “from the issuing of a decree to restore and rebuild Jerusalem, until Messiah the Prince”—up to the time of His manifestation at His baptism.

Therefore, as discussed in Part 1 of the Artaxerxes article under “The ‘Weeks’ of Daniel 9:25 were Sabbatical Year Cycles,” the separate mentions of the seven and sixty-two weeks does not involve inserting a chronological gap of unknown duration between them. Without clear evidence for a gap, and in the face of strong evidence against one—namely, the presence of the Lord Jesus on Planet Earth at the right time when no gap is assumed, and without recourse to the dubious idea of “prophetic years”—sound logic demands that we take the position which explains the most factors without exegetical creativity purely for the sake of rescuing a theological construct. As Occam’s Razor teaches us, the simplest explanation that accounts for all the factors is probably the correct one. For these reasons it appears there was no gap separating the seventh week from the 62 that followed it. They constituted a continuous period of 483 years.

Thus understood, the perspective of this study is that the first 69 weeks of Daniel’s prophecy was an unbroken span of time from the issuing of the decree in the seventh year of Artaxerxes until the baptismal anointing (Acts 10:37–38) of Jesus Christ—483 years. When the one remaining week is added to the count, we arrive at 490 years—ten Jubilees set aside by the Lord for the Jews and their holy city. What a perfect number.

The Gap after the Sixty-Ninth Week: Theological Considerations

With the birth of the Church at Pentecost after the Lord’s crucifixion, God’s focus turned entirely from the Jews to the Gentiles. Peter saw his vision that the Gentiles were no longer to be regarded as “unclean” (Acts 10), and Paul went forth preaching the message of salvation by faith alone in the Messiah, not in keeping the precepts of the Law. These changes signified the drastic turn in the Divine dealings with humanity from the Jews and Jerusalem to the Gentiles. However, this process had begun during the Lord’s earthly ministry, when He spoke in parables to the Jewish multitude so that only the elect, those to whom insight was “granted,” might understand (Mt 13:10 ff). It is also seen earlier in John’s gospel, when Jesus tells the woman at the well, “But an hour is coming, and now is, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth” (Jn 4:23). The change in how God saved people was already in effect—the Temple and its priesthood were no longer the mediators between God and man. And the change is seen even earlier, in His discussion with Nicodemus in John 3:3–7 about the necessity of being born again.

Therefore, I believe we should posit that at the time the Messiah was anointed, God changed the object of saving faith from the keeping of Temple-based ordinances to “the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” (Jn 1:29). The count of sabbatical year cycles progressed from Tishri 1, 457 BC to the very end of the 69th week, when it was interrupted at the time the Messiah was manifested at His baptism on or shortly after Tishri 1, AD 27. At that time the Father began turning His attention from the Jews and their holy city, an elect race, to an elect people where ancestry no longer mattered. Yes, Jesus was sent first to the “lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Mt 10:5–6), but now they were “found” by faith in the Messiah, not in keeping the Torah’s prescriptions.

The Gap after the Sixty-Ninth Week: Grammatical Considerations

Consistent with the above theological considerations, there is also a clear grammatical indicator of a chronological break between the end of the 69th week, immediately after which Christ was baptized, and the start of the 70th week. It is the preposition “until” (Heb. עַד `ad) in Daniel 9:25 alluded to earlier:

So you are to know and discern that from [1] the issuing of a decree to restore and rebuild Jerusalem until [2] Messiah the Prince there will be seven weeks and sixty-two weeks…

The lexicons show that `ad takes the meanings “as far as, even to, up to, until, while.” The context makes it clear that this passage is talking about the period of time that runs from event [1] to event [2]: the span of 69 sabbatical year cycles between the issuing of the decree in Artaxerxes’ seventh year and the manifestation of the Messiah. Since “until” in verse 25 signifies the 483 years must conclude before the Messiah comes, His crucifixion would necessarily have taken place after those 69 weeks ended, not during them. So, if the Crucifixion happened after the 69th week but before the 70th, there must be a gap, an interregnum, in the sabbatical cycle counting. That is simple logic, is it not? From these considerations it follows that Daniel’s Seventieth Week is still future.

The word “after” (Heb. אַחַר ‘achar) in Daniel 9:26 also corroborates this significance of “until,” by establishing a time indicator shared by two separate events:

Then after the sixty-two weeks [1] the Messiah will be cut off and have nothing, and [2] the people of the prince who is to come will destroy the city and the sanctuary. And its end will come with a flood; even to the end there will be war; desolations are determined.

Far too many prophecy teachers, by uncritically taking Anderson and/or Hoehner at their word rather than carefully examining the text of Daniel for themselves, have overlooked the important word “after” and placed the “cutting off” of the Messiah during Daniel’s 69 weeks rather than in the gap after it. The bracketed numbers indicate that two distinct events—the Crucifixion and the AD 70 destruction of the city and sanctuary—share the same time indicator. Hence, both must be placed in the interregnum between the end of the 69th week and start of the 70th. Following the word “after,” Daniel says several things take place: the Messiah would be “cut off”; Jerusalem and its Temple would be destroyed (fulfilled in AD 70); and war and desolations (note the plural) would take place. These things take time. It is only following these intervening events that the one remaining week in the prophecy is introduced in 9:27. Hence, those things do not happen during the 70th week, but precede it. And since the 70th week arrives after an indeterminate period of time following the destruction of Jerusalem, it indicates a fashionable theology of our day, preterism, fails to do justice to a straightforward understanding of Scripture.

The “Anointed One” in the Gap

If we search the New Testament for associations of Jesus with “anointed,” one verse that comes up is Acts 10:37–38:

You yourselves know what happened throughout all Judea, beginning from Galilee after the baptism that John proclaimed: how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power.

This verse makes a direct association between Jesus’ baptism and God’s actions at that time which distinctively made Him the Anointed One. Matthew 3:16–17 (NASB footnote: literally, “coming upon Him”), Luke 3:22 (“the Holy Spirit descended upon Him in bodily form like a dove”), and particularly John 1:31–33 further attest to this:

“I did not recognize Him, but so that He might be manifested to Israel, I came baptizing in water.” John testified saying, “I have seen the Spirit descending as a dove out of heaven, and He remained upon Him. I did not recognize Him, but He who sent me to baptize in water said to me, ‘He upon whom you see the Spirit descending and remaining upon Him, this is the One who baptizes in the Holy Spirit.’”

This manifesting of the Messiah could not have been through the Triumphal Entry on Palm Sunday as some prophecy teachers suggest, for that event offers no explanation of how Jesus was anointed. Besides, those who hailed the Lord’s entry that day were a fickle mob who immediately turned against Him—worldly Jews seeking only a political deliverer. Of these people the Lord said in Luke 19:41–44:

When He approached Jerusalem, He saw the city and wept over it, saying, “If you had known in this day, even you, the things which make for peace! But now they have been hidden from your eyes. For the days will come upon you when your enemies will throw up a barricade against you, and surround you and hem you in on every side, and they will level you to the ground and your children within you, and they will not leave in you one stone upon another, because you did not recognize the time of your visitation.”

Only those few whose eyes were opened by the Spirit were able to recognize the time of their visitation, the manifestation of the Anointed One which marked the transition from the Temple-based system of righteousness based on sacrifices and Law-keeping, to one based on grace and being born again by the Spirit of God (Jn 3:3–7). For these reasons I am quite confident the “manifestation” of John 1:31–33 is the fulfillment of the words “until Messiah the Prince” in Daniel 9:25. John the Baptist was the forerunner (Mt 11:10, Mk 1:2–3, Lk 1:17, Jn 3:28) whose ministry gave notice that the long-promised Anointed One had arrived, when we may say that the Shekinah glory of God’s Presence came to rest and remain upon Jesus of Nazareth. It was no longer in the Temple. This was the glory the disciples later saw with unveiled eyes during the Transfiguration (Mt 17:2).

The Future Fulfillment of the Seventieth Week

If Daniel’s 69th week ended before the Messiah was “cut off,” that leaves one more week in the prophecy still to be accounted for. Verse 27 sets that out:

And he will make a firm covenant with the many for one week, but in the middle of the week he will put a stop to sacrifice and grain offering; and on the wing of abominations will come one who makes desolate, even until a complete destruction, one that is decreed, is poured out on the one who makes desolate.

If we insist on chronological continuity of the 70th week with the 69 that preceded it, it stands to reason the Messiah was crucified during the 70th week. But this begs the question of why the prophecy did not simply say, “in the seventieth week the Messiah will be cut off.” Furthermore, the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple are included in the post-69th week period, which did not happen until Titus marched his legions into Jerusalem and burned the Temple about 40 years after the Crucifixion. “Desolations” are included in this period as well; by analogy with the desolations following the Babylonian exile, which did not end until after the Temple was rebuilt by Zerubbabel, it can be argued that in our own day the land of Israel remains in a state of desolation because many Jews are still scattered among the nations, Muslims still control access to the Temple Mount, and the Temple has not yet been rebuilt. And most obviously, it is not until verse 27 that “one week,” the final week of the 70, gets mentioned—after the Messiah is cut off and the Temple is destroyed.

A Few Thoughts about Preterism

At this point a bit must be said about preterism, because its tenets conflict with the plain sense of Daniel 9:24–27. Its foundational premise, inseparable from the allegorical/symbolic approach to interpretation it relies on, is that the bulk, if not all, of the eschatological material in Matthew 24 and Revelation has already been fulfilled through the fall of Jerusalem in AD 70. Preterists are forced to discount the testimony of Irenaeus, in Against Heresies 5.30.5, that John was banished to Patmos by Domitian around AD 95. They claim that Nero was the emperor who banished him, allowing them to say Revelation was written around AD 65 and thus preceded the destruction of Jerusalem; hence, much of the book was fulfilled in Roman actions against the Jews.

However, the historical evidences that Revelation was written after AD 90 during Domitian’s reign are varied and strong. The external evidences listed at https://www.biblestudytools.com/commentaries/revelation/introduction/early-testimony.html include statements from Irenaeus, Eusebius, Hegesippus, Tertullian and Origen. Gordon Franz, in his article “Was ‘Babylon’ Destroyed when Jerusalem Fell in A.D. 70?,” also observes that the apocryphal book The Acts of John clearly states that John wrote the book of Revelation on Patmos during Domitian’s reign. Franz notes that preterist Peter Gentry selectively quotes from that book to make it sound favorable to his position:

After John demonstrates his power by drinking deadly poison [cf. Mark 16:18], and raising a couple of people from the dead, Domitian banishes him to an island. The last part of Gentry’s quote is, “And Domitian, astonished at all the wonders, sent him away to an island, appointing for him a set time. And straightway John sailed to Patmos.” Unfortunately for Gentry, the sentence does not end there. It goes on to say, “where also he was deemed worthy to see the revelation of the end” (ANF 8:560–562). The Acts of John clearly support the “late date” for the writing of Revelation and a futuristic view of prophecy, not the fulfillment in AD 70 with the destruction of Jerusalem. Yet Gentry seems to be selective in his quotes to prove his point.

Moreover, there are strong internal evidences within Revelation itself that preterism must ignore or explain away. Not the least of these is the overview the Lord gives John at the outset of the book: “Therefore write [1] the things which you have seen, and [2] the things which are, and [3] the things which will take place after these things” (Rev 1:19). These instructions about what John is to write are surely not given in symbolic language. The first addresses the initial vision from 1:10–20; the second covers the spiritual state of the seven churches of John’s day described from 2:1–3:22; and the last covers 4:1 through the end of the book, events to happen after the book was written and distributed to the churches. Even the very first verse alludes to this truth, when John writes that he is about to describe things that “will soon take place”—i.e., in the future. The same thing is affirmed all the way at the end of the book (Rev 22:6). So even if preterism insists that the book was written in Nero’s day, the content of the book itself looks to the future. My sense is that preterists need to seriously consider whether their approach falls under the warning given at the very end of the book: “if anyone takes away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God will take away his part from the tree of life and from the holy city, which are written in this book” (Rev 22:19).

John also declares that Revelation was both a vision and a prophecy (Rev 1:3; 9:17; 22:7, 10, 18, 19). Recall that Daniel 9:24 says a purpose of the Seventy Weeks is “to seal up vision and prophet.” The Two Witnesses, in what to all appearances is an event future to the writing of the book, are said to prophesy in Revelation 11:3: “And I will grant authority to my two witnesses, and they will prophesy for twelve hundred and sixty days, clothed in sackcloth.” To maintain their view, preterists must give evidence that two individuals arose during Nero’s reign, while the Second Temple was still standing (Rev 11:1), who worked miracles for 3-1/2 years, were killed, openly resurrected three and a half days later before enemy eyewitnesses, and whose raising was followed by a great earthquake that destroyed a tenth of Jerusalem (Rev 11:13). None of these things are even hinted at in the ancient historical records that have survived, indicating they remain future. We should conclude that “vision and prophet” have not yet been sealed, so it follows that Daniel’s Seventy Weeks were not fulfilled in Roman times.

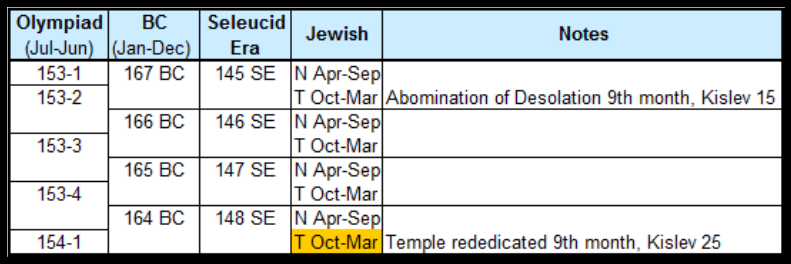

A little bit of reflection shows that if the exegesis of Daniel 9:24–27 presented in this study is correct, with the fall of Jerusalem taking place during an interregnum between the 69th and 70th weeks, then preterism cannot be reconciled with Daniel 9:24–27. It requires the fall of Jerusalem to Titus in AD 70 to be placed in the 70th week, but the plain sense of Daniel 9:26 puts it between the 69th and 70th. Everything specified in Daniel 9:27 belongs to the final seven years and is still future: the “firm covenant” with the many, the stopping of sacrifice and grain offering, the abomination of desolation, and the final defeat of the Antichrist. The historical events that prefigured them during the reign of Antiochus Epiphanes happened during the 69 weeks leading up to the manifestation of the Messiah, not during the interregnum or the 70th week. This determination is based solely on Daniel 9:24–27, without reference to Matthew 24 or Revelation. Those two books should be viewed through the lens of the prior revelation given to Daniel, not the other way around. The principle of “progressive revelation” applies, where information in Scripture is interpreted in the light of what was already revealed. We must not start with Revelation and attempt to interpret Daniel from it.

Who was “He” in Daniel 9:27?

In April 2020 I received an email from someone reading through my Daniel studies:

I would very much appreciate your take on the identity of the person referred to with the pronoun “he” of verse 27......”And he shall make a strong covenant with many for one week.....” Hopefully this subject will comprise a portion of an article as you reach that verse. To me the answer to that question is an eschatological keystone.

It is time to tackle that question. Let’s begin by pulling together verses 25–27, with extraneous text about the destruction of Jerusalem removed and no verse divisions to obscure what the pronouns refer to:

Then after the sixty-two weeks the Messiah will be cut off and have nothing, and the people of the prince who is to come will destroy the city and the sanctuary.... And he will make a firm covenant with the many for one week, but in the middle of the week he will put a stop to sacrifice and grain offering; and on the wing of abominations will come one who makes desolate, even until a complete destruction, one that is decreed, is poured out on the one who makes desolate.

I have bolded what appear to be at least two, probably three, distinct individuals:

(1) The masiach, the Anointed One. He is cut off—crucified—sometime during the interregnum after Daniel’s 69th sabbatical year cycle concludes and before the 70th begins. In the act of being cut off He drops out of the immediate context, and therefore cannot be the antecedent of “he” later in the passage.

(2) The “prince who is to come.” He shows up at the start of the 70th sabbatical year cycle, when he makes a “firm covenant” with the Jews for that “one week.” Since he was still “to come” at the time Jerusalem was destroyed in AD 70, this person had nothing to do with that destruction. According to Josephus, those whose hands actually destroyed the city and the sanctuary in AD 70 were Roman legions (Legio XV Apollinaris, Legio V Macedonica, Legio XII Fulminata, and Legio X Fretensis) drawn largely from Arabia and Syria. This indicates the “prince to come” would arise from Islamic ancestors. (Helpful overviews of the historical source information from Josephus and Tacitus can be found at https://revelation-now.org/wp-content/uploads/The-People-of-Baal-Destroyed-the-Temple-in-70-AD.pdf and https://www.myscripturestudies.com/2011/09/who-were-legions-of-rome.html.) To the point: since the Messiah of verse 25 had already been cut off, the “prince who is to come” is the only possible grammatical antecedent of “he” in Daniel 9:27. Because the Jewish religious practices he puts a stop to require a Temple, it must be rebuilt, so it definitely looks like a future event.

(3) The “one who makes desolate.” Although it is grammatically possible that this person is the same as the “prince to come,” the fact that the reference changes from “he” to “one” implies someone else is in view. This may be the same individual as the false prophet who is introduced after the Antichrist in Revelation 13:11.

So, “he” is the “prince to come.” He first shows up during the post-69th week interregnum, a time of unspecified duration. This rules out both Antiochus Epiphanes and Onias III from the Maccabean era, for they lived during Daniel’s first 69 weeks. Titus, however, arose after the 69th week; could he be identified with the “prince to come”? This is not possible either, because he made no covenant with the Jews that he later violated after 3-1/2 years; moreover, Titus was a native Roman with no ethnic connection to the Syrian legionnaires who did the actual Temple destroying (Titus wanted to preserve it). We must look for someone else as the “prince to come,” someone arising out of the post-69th week interregnum and by his covenant with “the many”—in context meaning the Jews, the “people and city” of Daniel which the whole prophecy applies to—initiates the last week of the 70. Since “sacrifice and grain offering” are intimately connected with that final week, and since there has been no Temple to make them possible since the Roman legions destroyed it 1,950 years ago, a necessary prerequisite for beginning Daniel’s 70th week is the rebuilding of the Temple. Therefore, since “sacrifice and grain offering” still have not been reinstated, we are still in the post-69th week interregnum. (Notice that positing a rebuilt Temple here has nothing to do with dispensational theology, but is an essential inference of the prophecy; how can the Jews restore “sacrifice and grain offering” without a Temple and priesthood to offer them?).

Conclusions

The purpose of this article has been to build upon the many months of research involved in The Daniel 9:24–27 Project to understand key aspects of the final two verses of the prophecy. This investigation has been Bible-centered from beginning to end. I did not approach the passage with the intention of using it to validate or disprove any particular system of theology, whether reformed, dispensational, adventist, preterist, pre-trib, post-trib, or anything else. My goal was simply to determine, to the best of my ability, what the plain sense of this fascinating passage taught. I found myself disagreeing with some teachers of considerable repute on important details, while agreeing with them on others.

In the end, all I can say is that I followed the biblical and historical evidence where it seemed to be leading. With prayerful dependence on the Holy Spirit, I used the skills developed from my seminary training, my innate orientation to detail (over the years I variously worked as a draftsman, medical technologist and computer programmer), and my love of ancient history and systematic theology to arrive at my own conclusions. Looking back over this work, I have a lot of confidence those conclusions rest on solid reasoning mixed with, I trust, spiritual sensitivity. The reader must judge whether I succeeded. My hope is that the Lord will be pleased to use these efforts to help unseal the book of Daniel in our day. After all, He did say in Daniel 12:9, “the words are shut up and sealed until the time of the end.” They will not always be sealed.

I am not certain what direction The Daniel 9:24–27 Project will take after this. In these articles I have tried not to go off into eschatology more generally, but limited myself to getting a comprehensive (!) understanding of Daniel 9:24–27. Perhaps, God willing, this work will serve as a springboard to jump into the minefield of competing theological loyalties which constitutes eschatology studies today. We shall see how He leads.

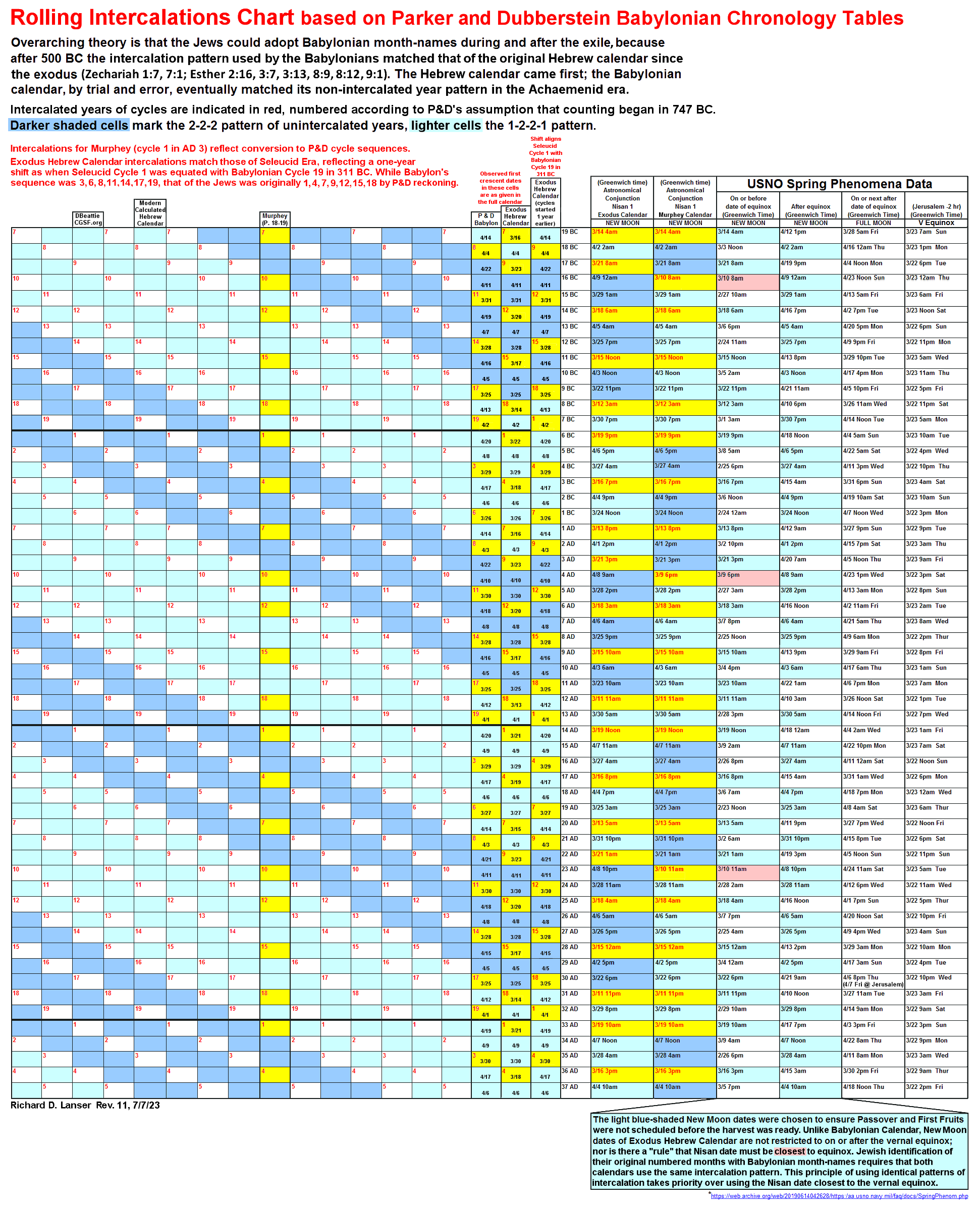

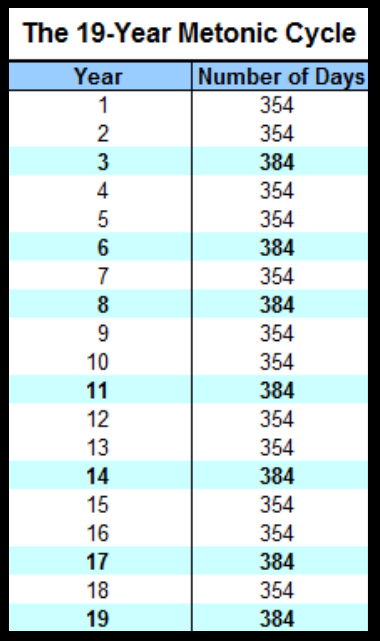

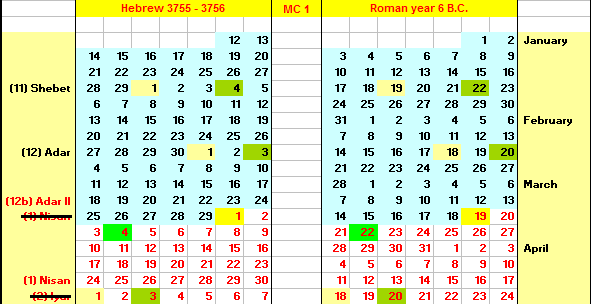

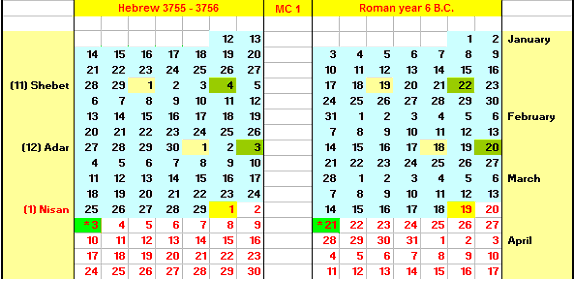

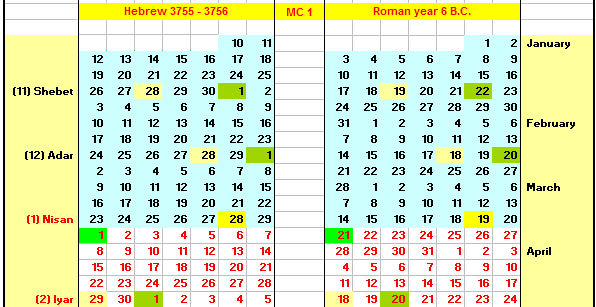

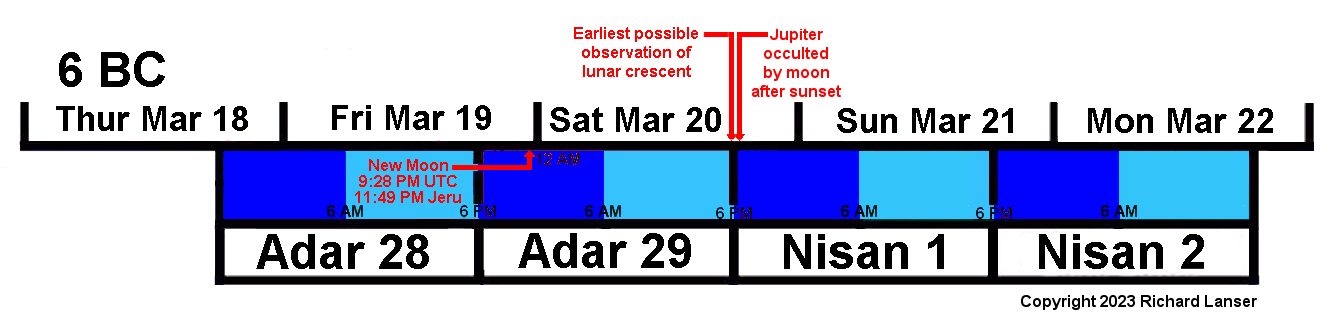

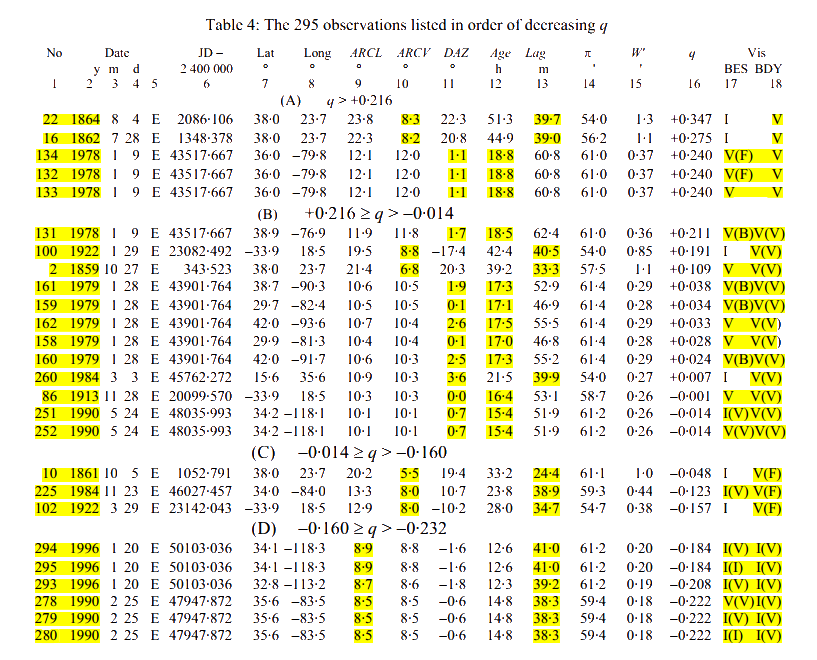

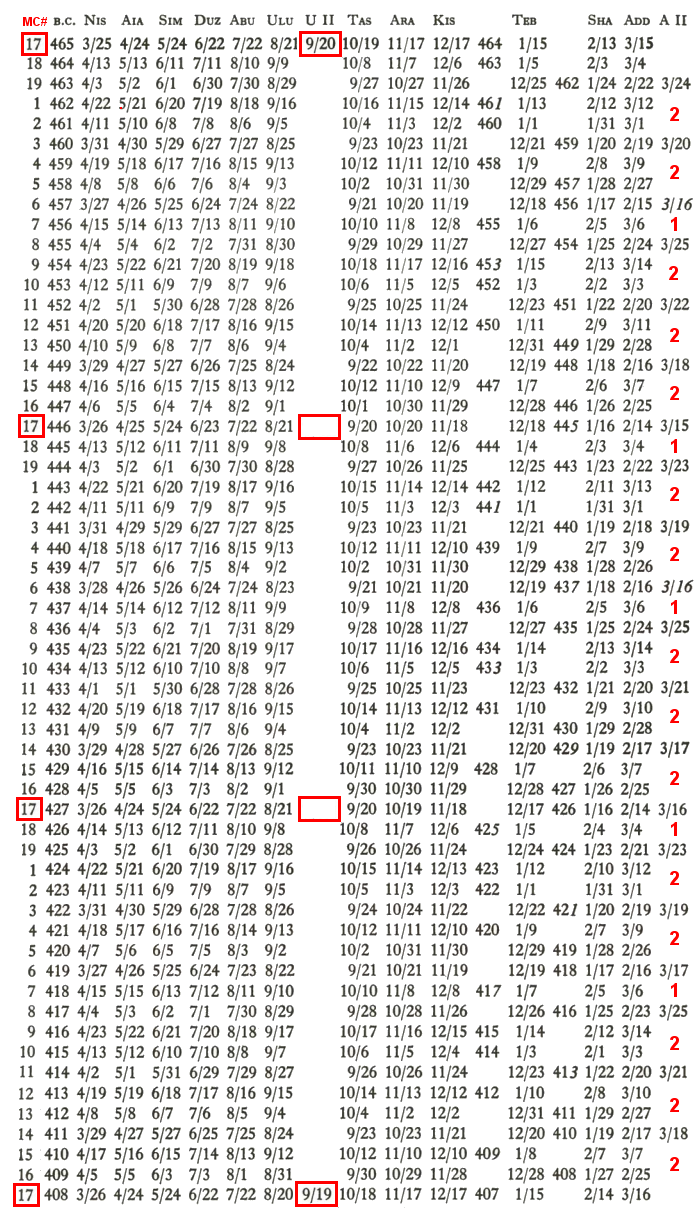

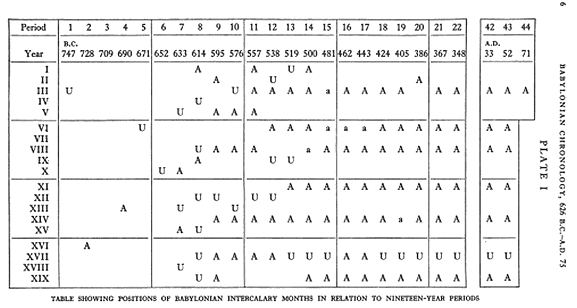

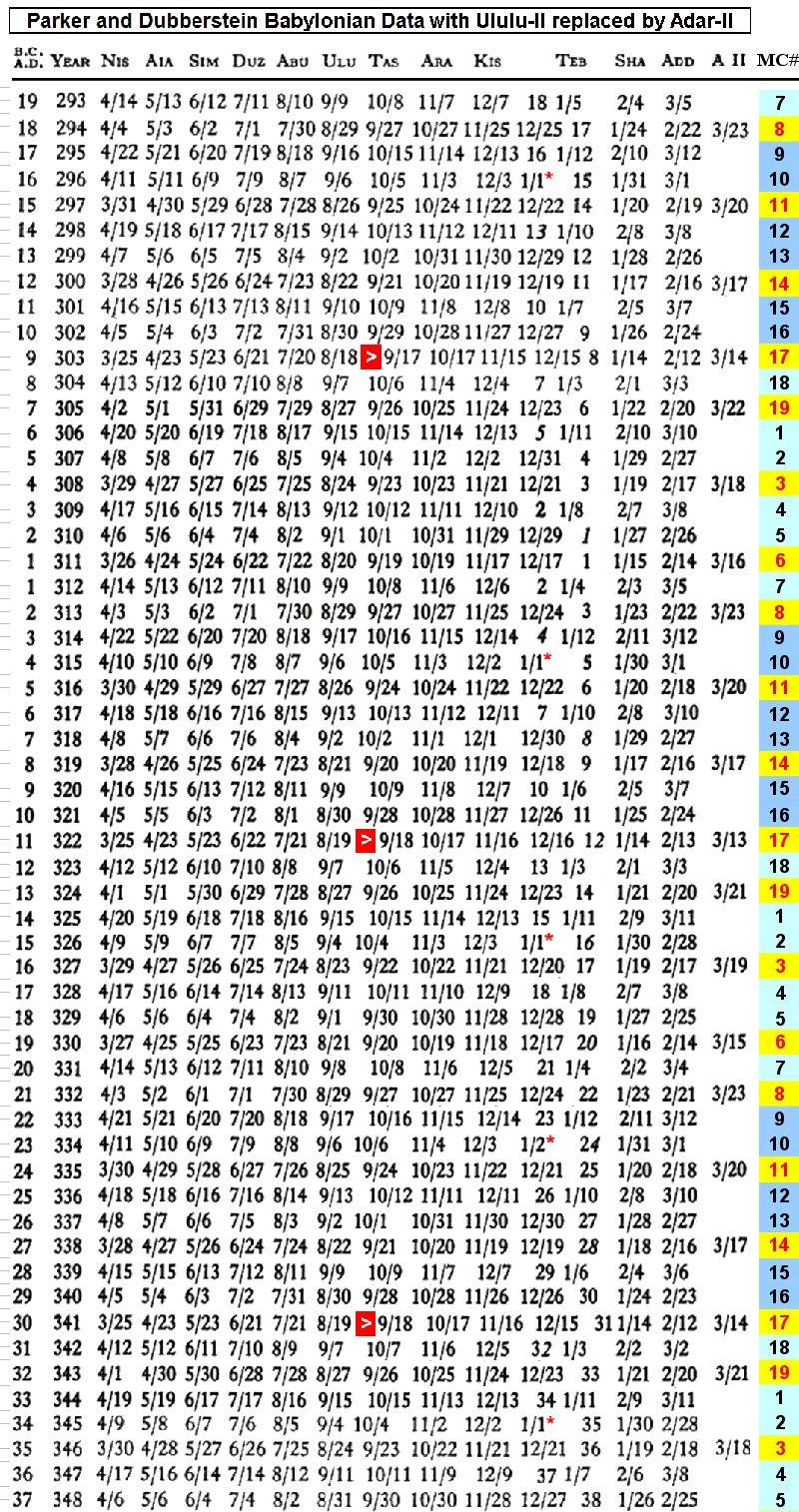

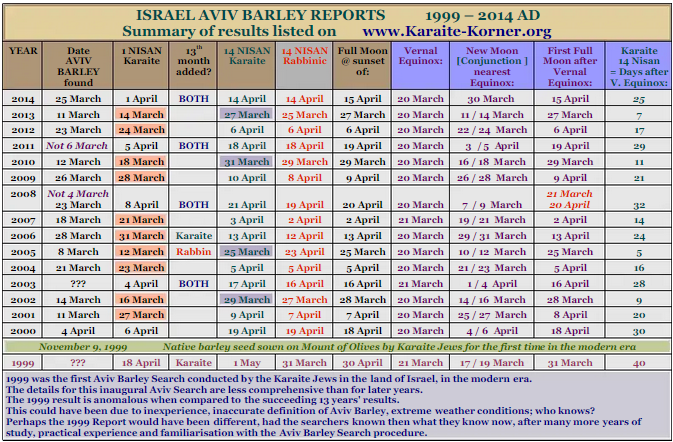

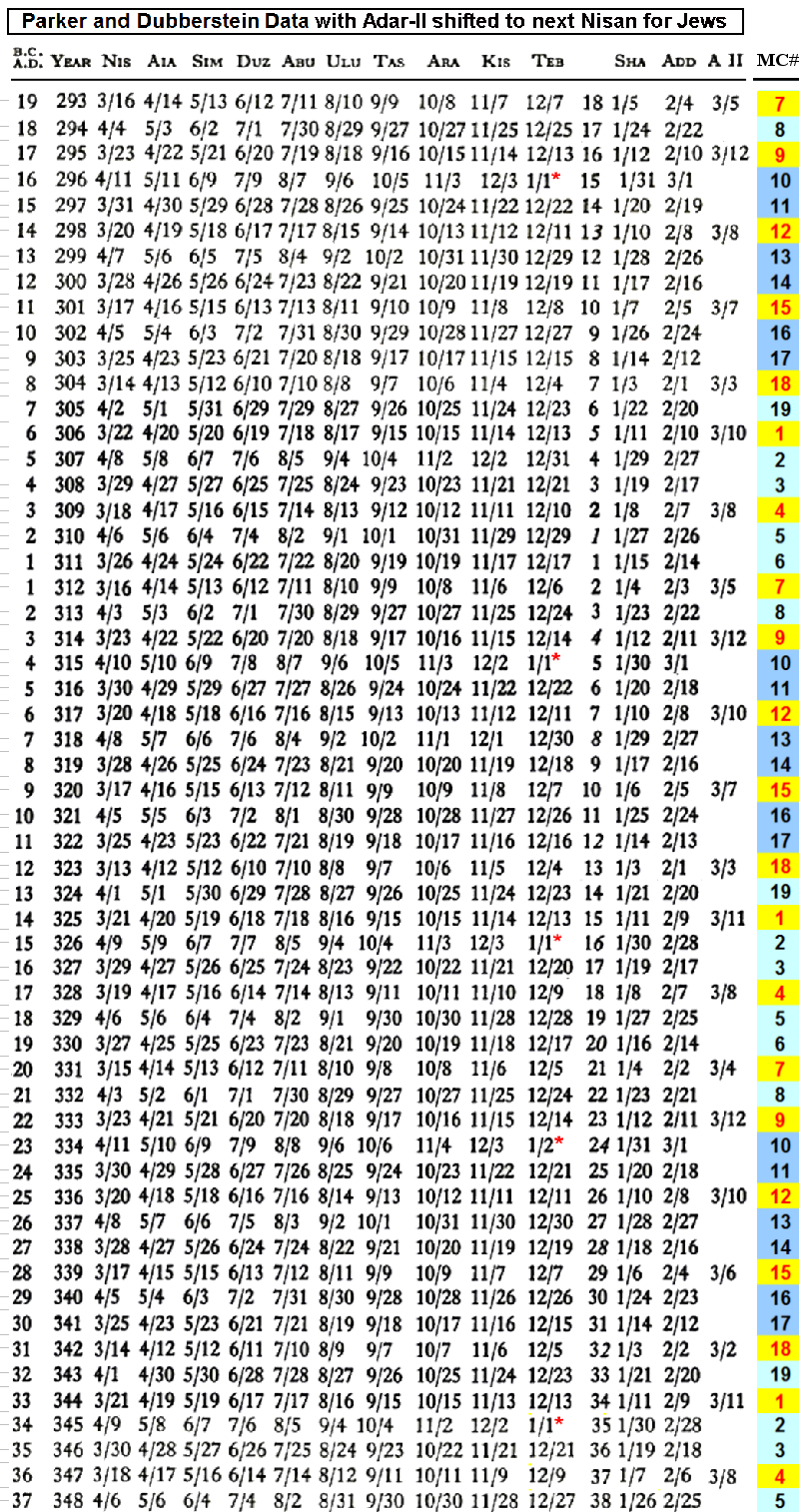

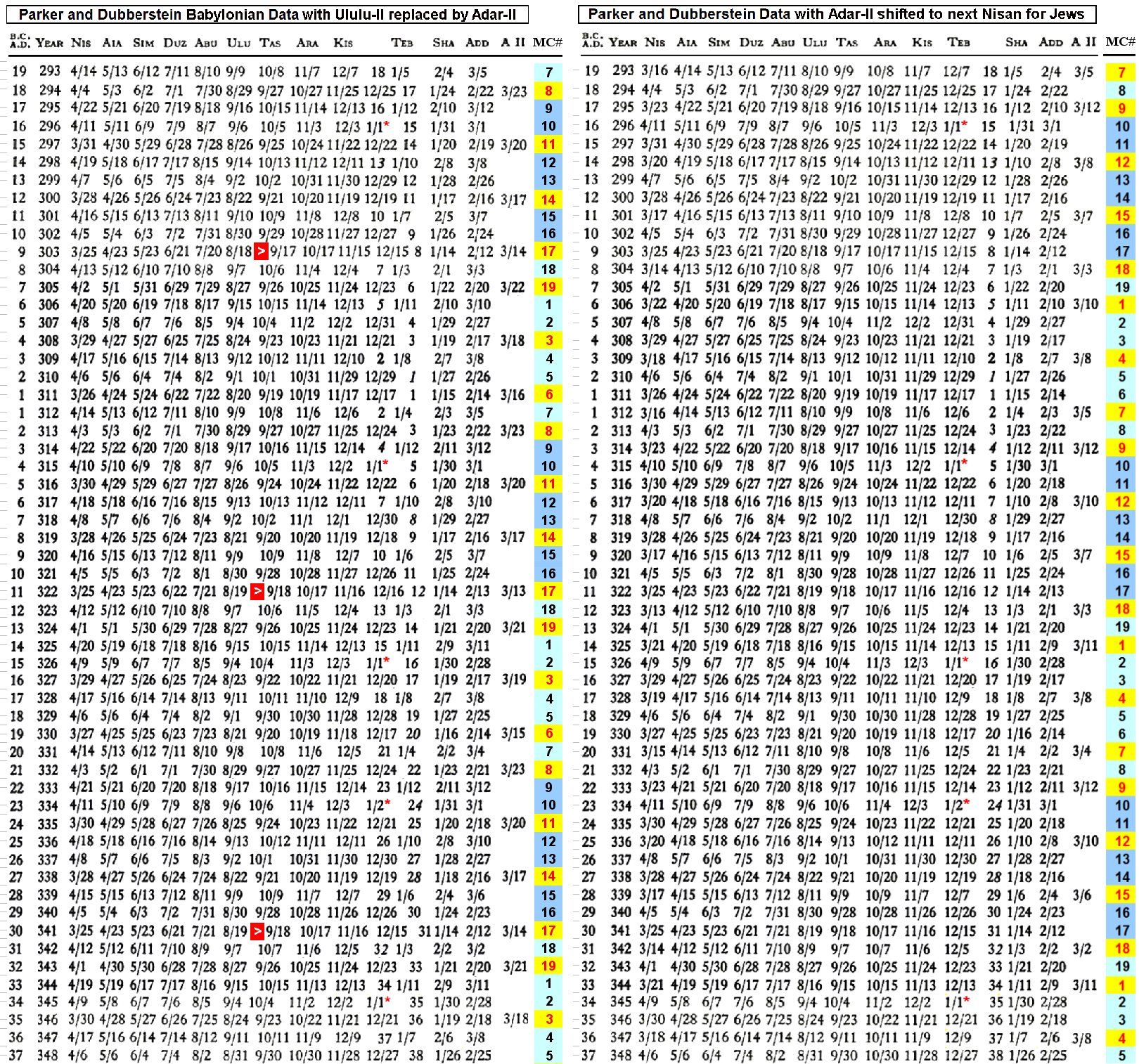

This calendar demonstrates how the 2-2-1-2-2-2-1 pattern and the conjunction New Moons of every month fit together with the first visible crescents of the Babylonians from 19 BC through AD 38. The first visible crescents reported by the Babylonians unfailingly begin not more than three days after every conjunction. This indicates the reliability of the adapted Babylonian data (with the Adar-II > Nisan shift) as an indicator of the Jewish observed first crescents, showing that we need not assume dependence on the vernal equinox by the early Hebrews. This approach to creating a calendar avoids the subjectivity involved in deciding if any particular first crescent observation at Babylon matched up with that at Jerusalem.

This calendar demonstrates how the 2-2-1-2-2-2-1 pattern and the conjunction New Moons of every month fit together with the first visible crescents of the Babylonians from 19 BC through AD 38. The first visible crescents reported by the Babylonians unfailingly begin not more than three days after every conjunction. This indicates the reliability of the adapted Babylonian data (with the Adar-II > Nisan shift) as an indicator of the Jewish observed first crescents, showing that we need not assume dependence on the vernal equinox by the early Hebrews. This approach to creating a calendar avoids the subjectivity involved in deciding if any particular first crescent observation at Babylon matched up with that at Jerusalem. It will be noted in the chart that I did not use the USNO’s earlier lunations in 16 BC, AD 4 and AD 23 (tinted in red – March 10, 9 and 10 respectively) for the Exodus Hebrew Calendar, instead assigning Nisan to the corresponding subsequent lunations on April 9, 8 and 8 (the last at 10 pm Greenwich time, therefore on Jewish date April 9). The earliest acceptable astronomical New Moon in the Exodus Hebrew Calendar is on March 11, seen in AD 12 and 31, because it fits the 2-2-1-2-2-2-1 pattern of the Babylonian data in P&D and the Karaite data. The latest acceptable Nisan 14 date is April 22.

It will be noted in the chart that I did not use the USNO’s earlier lunations in 16 BC, AD 4 and AD 23 (tinted in red – March 10, 9 and 10 respectively) for the Exodus Hebrew Calendar, instead assigning Nisan to the corresponding subsequent lunations on April 9, 8 and 8 (the last at 10 pm Greenwich time, therefore on Jewish date April 9). The earliest acceptable astronomical New Moon in the Exodus Hebrew Calendar is on March 11, seen in AD 12 and 31, because it fits the 2-2-1-2-2-2-1 pattern of the Babylonian data in P&D and the Karaite data. The latest acceptable Nisan 14 date is April 22.