The account of God raising up Moses to lead the people of Israel out of slavery in Egypt is one of the most important biblical events. In fact, it is the most frequently mentioned event in the entire Old Testament, referred to over 120 times in subsequent stories, laws, poems, Psalms, historical writings, and prophecies.1 In addition, there have been 3,500 years of almost unbroken Passover celebrations. The Exodus is such a seminal event in Hebrew history that it stretches credulity to suggest, as some critics do, that it did not have a historical basis.

Is there archaeological evidence for the Israelite exodus from Egypt? I believe there is, provided one recognizes the limits of archaeology and looks in the correct time period. First, one would not expect to find Egyptian inscriptions directly referencing the plagues or the Exodus, as royal inscriptions never included negative reports about the Pharaoh and his armies.2 Moreover, the Israelites wandered in the desert as nomads for 40 years, leaving little, if any, cultural remains due to their transient nature. This doesn’t mean that there is no evidence of the Exodus; it means one needs to look for the correct things (i.e., evidence of the decline of Egyptian society) and not expect to find the remains of Hebrew campsites in the desert. Secondly, one needs to look in the correct time period for clues to the Exodus. Fortunately, the Bible gives ample chronological data relating to this event. First Kings 6:1 says that it was “in the four hundred and eightieth year after the people of Israel came out of the land of Egypt” that Solomon began building the temple. A straightforward reading of this verse places the Exodus in 1446 BC.3 This timeframe is affirmed by numerous other passages: Judges 11:26–27, Acts 13:19–20, and the number of generations listed 1 Chronicles 6:33–38.4 Thus, one needs to look in the 15th century BC for evidence of the Exodus, not the 13th century BC as some scholars claim.5

Here, then, are the top ten discoveries related to Moses and the Exodus that I believe are evidence of the historicity of the biblical account.

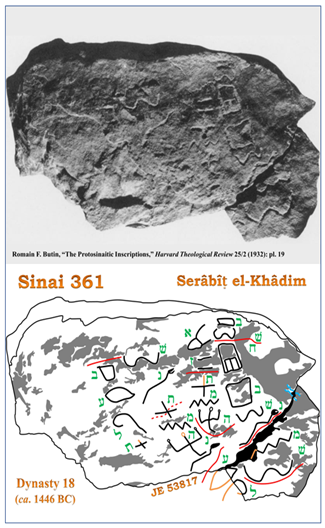

10. Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions

A Proto-Sinaitic Inscription

A Proto-Sinaitic Inscription

from Serabit el-Khadim (Sinai 361).

Image courtesy of Doug Petrovich.

Some have suggested that Moses did not write the first five books of the Bible, but that rather they were written a thousand years later by a supposed group of priests living in exile who were trying to invent a glorious history for their people. When this theory was first proposed in the 19th century, there was no known alphabetic script with which Moses could have recorded such lengthy reports. We now know that there was indeed an alphabetic script Moses could have used. Remember that Moses was literate, having been educated in Pharaoh’s household (Acts 7:22). In the early 20th century, Sir Flinders Petrie discovered examples of alphabetic writing inscribed on stones at Serabit el-Khadim, an Egyptian turquois mine in the Sinai.6 They date from the 19th to the 15th century BC.7 The proto-Sinaitic script, as it is often called, was invented by Semites who worked at the turquois mine and adopted Egyptian hieroglyphic symbols as pictographic letters for their language. Most scholars agree that the language behind this script is from Canaan, but which language it is has been a matter of debate. Douglas Petrovich has presented evidence that these inscriptions were written by Israelites, and that Hebrew is the language behind the script.8 His translation of one inscription (Sinai 361) contains the name of Moses.9 Not all scholars are convinced, however,10 and this has resulted in much debate.11 It is interesting that an alphabetic script developed at the precise time the Israelites were in Egypt, and that the language behind it is from their place of origin. At the very least, we now know that there was indeed an alphabetic script Moses could have used to write the first five books of the Bible.

9. Egyptian Words in the Hebrew Text

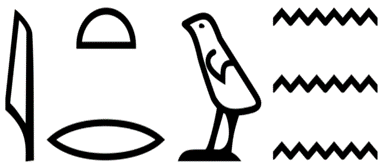

The Egyptian word for the Nile is “great river,” represented by these hieroglyphs, literally itrw, and “waters” determinative. The word “river” in the biblical account of baby Moses is not the normal Hebrew word for “river” (nahar), but rather a transliteration of this Egyptian word. Image: Wing/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0.

The Egyptian word for the Nile is “great river,” represented by these hieroglyphs, literally itrw, and “waters” determinative. The word “river” in the biblical account of baby Moses is not the normal Hebrew word for “river” (nahar), but rather a transliteration of this Egyptian word. Image: Wing/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0.

One of the often-overlooked elements of the Exodus account in the Bible is the use of Egyptian words in the Hebrew text. After the birth of Moses in the narrative, we read, “When she could hide him no longer, she took for him a basket made of bulrushes and daubed it with bitumen and pitch. She put the child in it and placed it among the reeds by the river bank” (Ex 2:3). Egyptologist James Hoffmeier has highlighted the numerous Egyptian words that are often missed in this verse. The Hebrew word for “basket” is tebat (nan) and derives from the Egyptian word dbjt. Similarly, the words “bulrushes” and “pitch” have Egyptian etymologies, and the Hebrew word “reeds” is unquestionably the Egyptian word twfy. The word “river,” clearly referring to the Nile, is not the normal Hebrew word for river (nahar) but rather a transliteration of the Egyptian word for the Nile.12 Even Moses’s name is Egyptian, having been given by Pharaoh’s daughter (Ex 2:10). Hoffemeier writes, “There is widespread agreement that at the root of the name of the great Hebrew leader is the Egyptian word msi, which was a very common element in theophoric names throughout the New Kingdom (e.g., Amenmose, Thutmose, Ahmose, Ptahmose, Ramose, Ramesses).”13 The Egyptian loanwords in the Hebrew text are difficult to explain unless one acknowledges Moses’s Egyptian education and authorship.

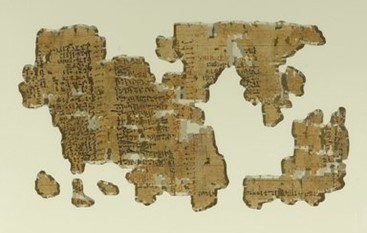

8. Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446

Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446 records the names of 95 household slaves, including some that are Hebrew.

Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446 records the names of 95 household slaves, including some that are Hebrew.

Photo: Brooklyn Museum / CC BY 3.0.

Central to the Exodus account is the presence of Israelites in Egypt to begin with. The Bible describes Joseph’s entrance to Egypt as a slave (Gn 37:28), his rise to power (Gn 41:41), his initiative in bringing his family to Egypt (Gn 45:18), their subsequent growth (Ex 1:7), and their eventual bondage (Ex 1:11). Some scholars, however, do not believe the Israelites were ever in Egypt. For example, in a 1999 article in Ha’aretz, Ze’ev Herzog boldly declared, “This is what archaeologists have learned from their excavations in the Land of Israel: the Israelites were never in Egypt, did not wander in the desert, did not conquer the land in a military campaign and did not pass it on to the 12 tribes of Israel.”14

There is evidence, however, of the Israelites in Egypt. Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446 is an Egyptian document written in hieratic script that names 95 household servants of a noblewoman named Senebtisi.15 Forty of the names are Semitic (Hebrew is a Semitic language),16 and several have been identified as Hebrew names. These include “Menahema,” a feminine form of the Hebrew name “Menahem” (2 Kgs 15:14), a woman whose name is a parallel to Issachar, one of Jacob’s sons (Gn 30:18), and also parallel to Shiphrah, the name of one of the Hebrew midwives prior to the Exodus (Ex 1:15).17 To be clear, this papyrus dates to the 13th Dynasty (ca. 1809–1743 BC),18 just after the time of Joseph, and does not refer to Hebrew slaves at the time of Moses. Titus Kennedy summarizes the papyrus’s importance: “This list is a clear attestation of Hebrew people living in Egypt prior to the Exodus, and it is an essential piece of evidence in the argument for an historical Exodus.”19

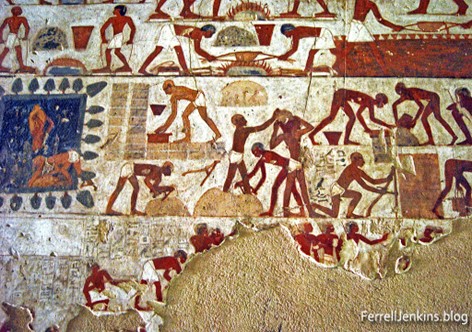

7. Egyptian Records of Slaves Making Bricks

A brickmaking scene in the tomb of Rekhmire

A brickmaking scene in the tomb of Rekhmire

in the Valley of the Nobles in Lower Egypt.

Photo: Ferrell Jenkins, https://ferrelljenkins.blog/2020/03/12/.

One of the tasks the Israelite slaves were pressed into was making bricks (Ex 5:7–8). When Moses petitioned Pharaoh to let God’s people go, Pharaoh responded by making their labor more difficult (Ex 5:6–18). The biblical description of slaves making bricks is affirmed by a painting in the tomb of Rehkmire (ca. 1470–1445 BC), the vizier of Egypt under Thutmose III and Amenhotep II. The painting depicts Nubian and Asiatic slaves (Egyptians called people from Canaan “Asiatics”) making bricks for the workshops of the Karnak Temple.20 Slaves are seen collecting and mixing mud and water, packing the mud in brick molds, and leaving the bricks to dry in the sun. Nearby Egyptian officials, each with a rod, oversee the work.

In addition to the Rehkmire tomb painting, a leather scroll in the Louvre that dates to the time of Rameses II mentions forty stablemasters (junior officers) who each had a quota of 2000 bricks to be made by the men under them.21 Two further Egyptian papyri (Anastasi IV and V) record that “there are no men to make bricks and no straw in the district,”22 highlighting the importance of straw as a binder in brickmaking, as well as the dismay the Israelites would have felt when Pharaoh stopped supplying it but still required the same number of bricks to be made (Ex 5:18–21). Egyptian records affirm the biblical description of the process of making bricks.

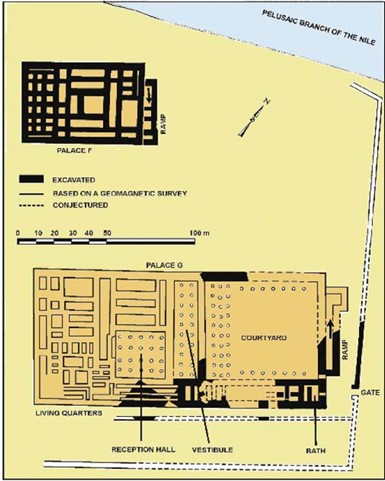

6. Discoveries at Avaris

The city of Avaris beneath the city of Rameses.

The city of Avaris beneath the city of Rameses.

Image: (c) Patterns of Evidence, LLC. Used with permission. https://patternsofevidence.com/

According to the biblical text, the Israelites settled “in the land of Rameses” (Gn 47:11) sometime in the 19th century BC. While they were initially free, at some point they became slaves to the native Egyptians and were pressed into building the city of Rameses (Ex 1:11). When they left Egypt in 1446 BC, some 430 years later, they departed from Rameses (Ex 12:37).23 The use of the word “Rameses” is an update of the biblical text by later editors to replace an archaic place-name with one that was more recognizable, as in Genesis 47:11: “Then Joseph settled his father and his brothers and gave them a possession in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land, in the land of Rameses, as Pharaoh had commanded.”

Palace F and Palace G from ancient Avaris date to the time of Moses. Image: Bryant G. Wood, Associates for Biblical Research. Based on figs. 4, 33, and 34b in Manfred Bietak, Josef Dorner, and Peter Jánosi, Ausgrabungen in dem Palastbezirk von Avaris. Vorbericht Tell el-Dab‘a/‘Ezbet Helmi 1993–2000, Egypt and the Levant 11 (2001): 27–119.

Palace F and Palace G from ancient Avaris date to the time of Moses. Image: Bryant G. Wood, Associates for Biblical Research. Based on figs. 4, 33, and 34b in Manfred Bietak, Josef Dorner, and Peter Jánosi, Ausgrabungen in dem Palastbezirk von Avaris. Vorbericht Tell el-Dab‘a/‘Ezbet Helmi 1993–2000, Egypt and the Levant 11 (2001): 27–119.

Thanks to five decades of excavations by the Austrian Archaeological Institute of Cairo at Tell el-Dab‘a in the eastern Nile Delta, we now know that this was the site of the city Rameses, which was itself built over a previous city named Avaris. While the site is most famous as the Hyksos capital,24 it was originally settled in the 19th century (the time of Joseph) by a group of non-Egyptians from Canaan, as evidenced by the Canaanite pottery and weapons they used.25 There is even evidence of a four-roomed house in the village (the same layout as houses typical in Israelite settlements in the later Iron Age), as well as a prominent tomb in which the remains of a statue of a Semitic man with a multicolored robe was found. The town grew and became more Egyptianized, with a mansion built atop the four-roomed house, which some believe to be the residence of Ephraim and Manasseh, Joseph’s sons.26 A palace precinct was later built at Avaris during the Hyksos period, and then expanded during the 18th Dynasty, forming a new royal citadel.27 This later palatial complex dates to the time of Moses and is likely where he spent time when he was raised in Pharaoh’s courts. Interestingly, the excavators at Tell el-Dab’a noted that the site was suddenly and mysteriously abandoned after the reign of Amenhotep II, suggesting that a plague may have been the reason.28 Bryant Wood summarizes the occupational history of the site: “The excavations at Tell el-Dab’a have revealed the presence of an ‘Asiatic’ community who first settled as pastoralists, then grew in number as well-to-do entrepreneurs, became subservient to the Egyptians and finally left. This scenario exactly matches what we read in the Bible.”29

5. Evidence for Amenhotep II as the Pharaoh of the Exodus

This granodiorite head of the 19th-Dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep was once part of a sphinx. It is currently housed in the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich, Germany.

This granodiorite head of the 19th-Dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep was once part of a sphinx. It is currently housed in the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich, Germany.

Photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0.

Numerous scholars have identified Amenhotep II as the Pharaoh of the Exodus;30 he was reigning in 1446 BC when the Israelites left Egypt. Amenhotep II is known to have spent considerable time in the delta region, likely in the 18th-Dynasty palace at Avaris, where he would have met with Moses. According to Egyptologist Charles Aling, “Amenhotep II was born and raised in this area [the Nile delta region], built there, had estates there, and in all probability resided there at times, at least in his early regnal years.”31 Interestingly (and in keeping with the tenth plague—the death of the firstborn), Amenhotep II was not the firstborn son of his father, Thutmose III, nor was Amenhotep’s son Thutmose IV his firstborn son.32

Another piece of evidence for identifying Amenhotep II as the pharaoh of the Exodus is found by comparing the military campaigns of Amenhotep II with those of his father. While Thutmose III led 17 known military campaigns into the Levant, Amenhotep II led only two or three.33 Thutmose III boasted of having taken 5,903 captives on his first campaign, while Amenhotep II claimed to have taken 2,214 captives on his first. However, Amenhotep II’s final campaign in the ninth year of his reign (ca. 1446 BC) appears to have been a hasty and limited excursion into Palestine to take 101,128 captives. One plausible explanation for this campaign and its dramatic number of captives is that he was seeking to replace a large portion of his slave-labor base that had just left Egypt.34 Moreover, Amenhotep II never took another campaign into Canaan, and the 18th Dynasty began to decline in power.

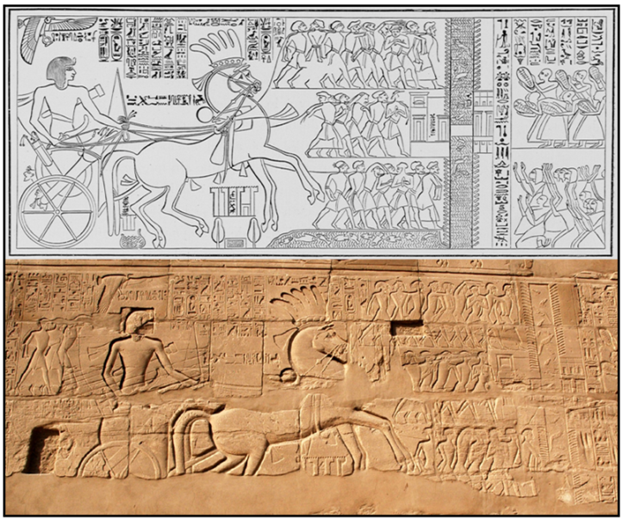

4. Seti War Relief

Seti I returns from his “first campaign of victory” in this relief from the north wall of the Hypostyle Hall in the Karnak Temple of Amun in Luxor. Top image: Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 2.0. Bottom image: Peter Brand, https://www.memphis.edu/hypostyle/tour_hall/seti_scenes.php.

Seti I returns from his “first campaign of victory” in this relief from the north wall of the Hypostyle Hall in the Karnak Temple of Amun in Luxor. Top image: Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 2.0. Bottom image: Peter Brand, https://www.memphis.edu/hypostyle/tour_hall/seti_scenes.php.

The famous relief of the campaigns of the pharaoh Seti I (ca. 1291–1279 BC) at the Karnak Temple depicts the eastern border of Egypt in pictorial form (like a map) and likely relates to the route Moses and the Israelites took during the Exodus. In Exodus 13:17 we read, “When Pharaoh let the people go, God did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near. For God said, ‘Lest the people change their minds when they see war and return to Egypt.’” The Seti relief depicts this road, known as the Horus Way, as well a number of fortresses, including “Tjaru,” the staging point for Egyptian campaigns into Canaan.35 A vertical waterway lined with reeds and labeled “the dividing waters” is visible, as well as a larger body of water at the bottom of the waterway (a feature that was seen by earlier explorers but is no longer visible).36 The Seti relief is evidence that there was, at one time in the distant past, a canal or waterway on the eastern border of Egypt, even though the area is a desert now.

This has been affirmed by geological studies that have demonstrated that there was indeed a man-made canal joining a string of lakes between the Gulf of Suez and the Mediterranean Sea. These canals and lakes—from the el-Ballah Lakes in the north to Lake Timsah to the Bitter Lakes in the south—formed a defensive barrier on the eastern frontier of Egypt. The Bible says that Moses led the Israelites through the Red Sea (in Hebrew, the yam suf, literally “sea of reeds”37), which may correspond to the wetlands and lake systems on Egypt’s eastern border.38 Egyptologist James Hoffmeier has matched Egyptian place-names with the locations mentioned in the Exodus itinerary and suggests that the yam suf the Israelites crossed was likely in the area of the el-Ballah Lakes.39

3. Soleb Inscription

The Soleb inscription of Amenhotep III names the “land of the Shasu [nomads] of Yahweh” as a place he claims to have conquered. Image: Soleb IV N 4 α: “the land of the Shasu of Yhwh.”

The Soleb inscription of Amenhotep III names the “land of the Shasu [nomads] of Yahweh” as a place he claims to have conquered. Image: Soleb IV N 4 α: “the land of the Shasu of Yhwh.”

Photo from J. Leclant, Les fouilles de Soleb (Nubie soudanaise): Quelques remarques sur les écussons des peuples envoutés de la salle hypostyle du secteur IV, NAWG.PH 13 (1965) 205–216: 214*, fig. 15 and c.

At the end of the 15th century BC, the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III built a temple to honor the god Amun-Ra at Soleb in Nubia (modern-day northern Sudan). He left a list of the territories he claims to have conquered on a series of columns in the temple. Each territory is depicted by a relief of a prisoner with his hands tied behind his back over an oval “name ring” identifying the land of the conquered foe. One of the enemies is from the “the land of the Shasu [nomads] of Yahweh.” Given the other name rings nearby, the context would place this land in the Canaanite region. In addition, the prisoner is clearly portrayed as Semitic, rather than African-looking, as other prisoners in the list are portrayed.40 Two conclusions are almost universally accepted: first, this inscription clearly references Yahweh in Egyptian hieroglyphics (the oldest such reference outside of the Bible41), and second, around 1400 BC Amenhotep III knew about the god Yahweh. Moreover, the Soleb inscription would indicate an area in Canaan in the 15th century BC inhabited by nomadic or seminomadic people who worshipped the god Yahweh. Charles Aling and historian Clyde Billington summarize: “If the Pharaoh of the Exodus had never before heard of the God Yahweh, this strongly suggests that the Exodus should be dated no later than ca. 1400 BC because Pharaoh Amenhotep III had clearly heard about Yahweh in ca. 1400 BC.”42

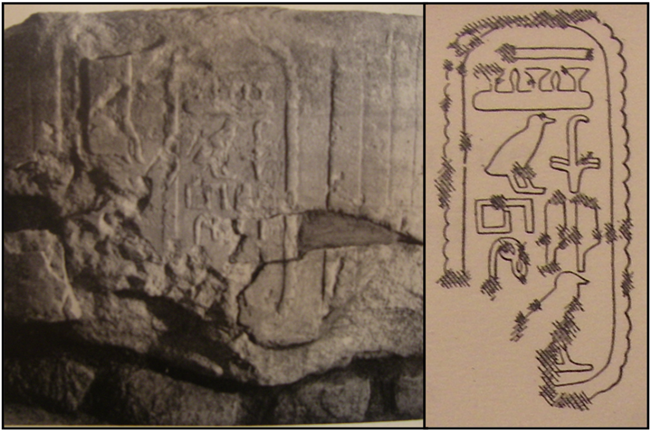

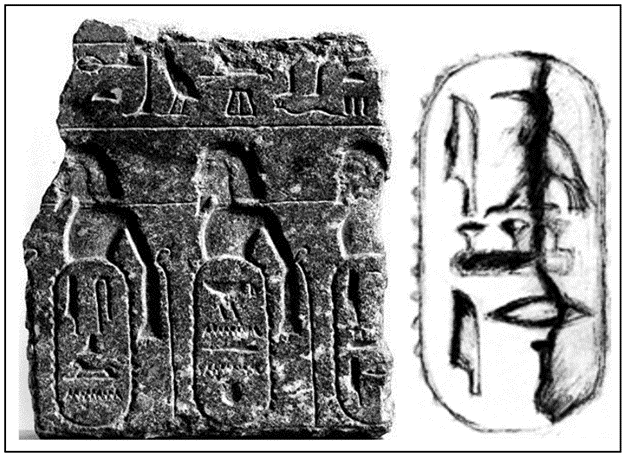

2. Berlin Pedestal

The Berlin Pedestal from the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. It has three name rings; the one on the far right has been reconstructed to read “Ishrael.” Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain. Reconstructed drawing: Peter van der Veen, Christoffer Theis, and Manfred Gorg, “Israel in Canaan (Long) Before Pharaoh Merenptah? A Fresh Look at Berlin Statue Pedestal Relief 21687,” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 2, no. 4 (2010): 21.

The Berlin Pedestal from the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. It has three name rings; the one on the far right has been reconstructed to read “Ishrael.” Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain. Reconstructed drawing: Peter van der Veen, Christoffer Theis, and Manfred Gorg, “Israel in Canaan (Long) Before Pharaoh Merenptah? A Fresh Look at Berlin Statue Pedestal Relief 21687,” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 2, no. 4 (2010): 21.

The Berlin Pedestal is an Egyptian inscription housed in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin that almost certainly refers to Israel as a nation in Canaan. The inscription has three name rings, two of which clearly read “Ashkelon” and “Canaan,” and the third of which has been reconstructed to read “Ishrael.”43 In a recent reexamination of the inscription, Peter van der Veen, Christoffer Theis, and Manfred Gorg noted that the names “Ashkelon” and “Canaan” largely were written consonantally and better reflect examples from the reigns of Tuthmosis III and Amenhotep II (15th century BC) than those from the times of Rameses II and Merneptah (13th century BC).44 While the inscription reads “Ishrael” instead of “Israel,” there is no other candidate near Canaan and Ashkelon other than biblical Israel. It may be that the “sh” spelling is an older way the Egyptians spelled “Israel” or perhaps is borrowed from the cuneiform version.45 If this interpretation is correct, it would indicate that the Israelites had migrated to Canaan sometime in the middle of the second millennium BC,46 exactly at the time the Bible says they did.

1. The Merneptah Stele

The Merneptah Stele (ca. 1208 BC) is a 10-foot tall granite victory monument that names Israel as a nation in Canaan. Photo: Todd Bolen, https://www.bibleplaces.com/2014/01/artifact-of-month-merneptah-stela/.

The Merneptah Stele (ca. 1208 BC) is a 10-foot tall granite victory monument that names Israel as a nation in Canaan. Photo: Todd Bolen, https://www.bibleplaces.com/2014/01/artifact-of-month-merneptah-stela/.

The most famous, and arguably the most important, discovery related to Moses and the Exodus is the Merneptah Stele. In ca. 1208 BC Pharaoh Merneptah erected a 10-foot tall victory monument (called a “stele”) in a temple at Thebes to boast of his claims of victory in both Libya and Canaan. It was discovered in 1896 by Sir Flinders Petrie. On it, Merneptah boasts, “Israel is wasted, its seed is not; And Hurru [Canaan] is become a widow because of Egypt.”47 The inscription likely refers to a small campaign into Canaan (only three cities were taken), and despite Merneptah’s boast, Israel was not destroyed.

Most scholars agree that this is the oldest definitive reference to Israel as a nation outside of the Bible, and certainly the clearest Egyptian reference to Israel. It is also important because it points toward an early date for the exodus (ca. 1446 BC) and not the late date that some scholars hold to (ca. 1270 BC). It is doubtful that there would be enough time from 1270 BC to 1208 BC to account for the Exodus, the 40 years of wandering in the desert, the seven-year Conquest of Canaan, the settlement of the tribes in their territories, and the establishment of a national presence in the land, all before Merneptah claims to have conquered the Israelites. Merneptah’s Canaanite campaign instead likely dates to the time of the Judges, when the nation of Israel was already settled in Canaan. The Merneptah Stele is evidence that the Exodus from Egypt, led by Moses, took place in the 15th century BC as the biblical data indicates.

Conclusion

Taken together, these ten discoveries indicate that the accounts of Moses and the Exodus are based in real history. While not the “proof beyond a shadow of a doubt” that many seek, they provide circumstantial evidence that can lead one to reasonably conclude that the people of Israel were slaves in Egypt at the time the Bible indicates. Further, the archaeological data suggests that the Israelites left suddenly and were settled in Canaan by the end of the 15th century BC, in line with the biblical data.

The video version of this blog, Episode 157 of the TV show Digging for Truth, can be viewed at this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B_Z9aUynQdE.

Endnotes

1 Yair Hoffman, “A North Israelite Typographical Myth and a Judean Historical Tradition: The Exodus in Hosea and Amos,” Vetus Testamentum 39, no. 2 (1989): 170, quoted in Randall Price and H. Wayne House, Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2017), 88.

2 James K. Hoffmeier, “Out of Egypt: The Archaeological Context of the Exodus,” in Ancient Israel in Egypt and the Exodus, ed. Margaret Warker (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 2012), 5.

3 Charles Aling, Egypt and Bible History (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1981), 96.

4 A good summary of the verses that point to an early date for the Exodus (and by implication the Conquest 40 years later) in the 15th century BC can be found in the following episodes of ABR’s TV show, Digging for Truth: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxXXTGD_y40&t=1312s and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-mUoS5RvBU&t=1379s.

5 Bryant G. Wood, “The Rise and Fall of the 13th Century Exodus-Conquest Theory,” Associates for Biblical Research, April 17, 2008, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/conquest-of-canaan/2579-the-rise-and-fall-of-the-13th-century-exodusconquest-theory (accessed September 16, 2021).

6 Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Sinaitic inscriptions,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, August 24, 2012, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sinaitic-inscriptions (accessed September 16, 2021).

7 Douglas Petrovich, “Hebrew as the Language of the World’s Oldest Alphabet,” Bible and Spade 30, no. 2 (Spring 2017): 54.

8 Douglas Petrovich, “Hebrew as the Language behind the World’s First Alphabet?,” American Society of Overseas Research 5, no. 4 (April 2017), https://www.asor.org/anetoday/2017/04/hebrew-first-alphabet (accessed September 16, 2021).

9 Steve Law, “New Discoveries Indicate Hebrew Was World’s Oldest Alphabet – Part 3,” Patterns of Evidence, January 19, 2017, https://patternsofevidence.com/2017/01/19/new-discoveries-indicate-hebrew-was-worlds-oldest-alphabet-part-3/ (accessed September 21, 2021).

10 Alan Millard, “A Response to Douglas Petrovich’s ‘Hebrew as the Language behind the World’s First Alphabet?,’” American Society of Overseas Research 5, no. 4 (April 2017), https://www.asor.org/anetoday/2017/04/response-petrovich (accessed September 16, 2021); Christopher Rollston, “The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions 2.0: Canaanite Language and Canaanite Script, Not Hebrew,” Rollston Epigraphy, December 10, 2016, http://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/?p=779 (accessed September 21, 2021).

11 See Douglas Petrovich’s responses to Alan Millard and Christopher Rollston at his academia.edu page: https://thebibleseminary.academia.edu/DouglasPetrovich.

12 James K. Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 138–39.

13 Ibid., 140.

14 Ze’ev Herzog, “Deconstructing the walls of Jericho,” Ha’aretz, October 29, 1999, http://websites.umich.edu/~proflame/neh/arch.htm (accessed September 18, 2021).

15 “Portion of a Historical Text,” Brooklyn Museum, accessed September 18, 2021, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/3369.

16 Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt, 61.

17 Charles Aling, “Joseph in Egypt - Part II,” Associates for Biblical Research, accessed September 18, 2021, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/patriarchal-era/3724-joseph-in-egypt-part-ii.

18 “Portion of a Historical Text,” Brooklyn Museum.

19 Titus Kennedy, “Hebrews in Egypt before the Exodus? Evidence from Papyrus Brooklyn,” APXAIOC, accessed September 18, 2021, https://apxaioc.com/?p=21.

20 Gary Byers, “The Bible according to Karnak,” Associates for Biblical Research, August 13, 2009, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/topics/egyptology/3216-the-bible-according-to-karnak (accessed September 20, 2021).

21 K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006), 247.

22 Ricardo A. Caminos, Late Egyptian Miscellanies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954), 105–106, 188–89, 225, in Robert and Lorenzon Littman and Jay and Marta Silverstein, “With and without Straw: How Israelite Slaves Made Bricks,” Biblical Archaeology Review 40, no. 2 (March/April 2014): 63.

23 Bryant Wood, “The Royal Precinct at Rameses,” Associates for Biblical Research, April 3, 2008, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/sojourn-of-israel-in-egypt/2249-the-royal-precinct-at-rameses (accessed September 17, 2021).

24 Manfred Bietak, Avaris, the Capital of the Hyksos: Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dab’a (London: British Museum Press, 1996), 7.

25 Bryant Wood, “New Evidence for Israel’s Sojourn in Egypt,” Bible and Spade 33, no. 1 (Winter 2020): 11.

26 Ibid., 13.

27 Manfred Bietak, Avaris, 67.

28 Manfred Bietak and Irene Forstner-Miller, “Ausgrabung eines Palastbezirkes der Tuthmosidenzeit bei ʿEzbet Helmi/Tell el-Dabʿa, Vorbericht für Herbst 2004 und Frühjahr 2005,” Ägypten und Levante 15 (2005): 93, 95, translated by Walter Pasedag, quoted in Bryant Wood, “New Evidence for Israel’s Sojourn in Egypt,” Bible and Spade 33, no. 1 (Winter 2020), 14.

29 Bryant Wood, “New Evidence for Israel’s Sojourn in Egypt,” Bible and Spade 33, no. 1 (Winter 2020): 11.

30 William Shea, “Amenhotep II as the Pharaoh of the Exodus,” Associates for Biblical Research, February 22, 2008, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/exodus-era/2455-amenhotep-ii-as-pharaoh-of-the-exodus; Douglas Petrovich, “Amenhotep II and the Historicity of the Exodus Pharaoh,” Associates for Biblical Research, February 4, 2010, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/exodus-era/3147-amenhotep-ii-and-the-historicity-of-the-exodus-pharaoh (accessed September 21, 2021); Charles Aling, Egypt and Bible History: From Earliest Times to 1000 B.C. (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1981).

31 Aling, Egypt and Bible History.

32 Petrovich, “Amenhotep II.”

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.

35 Gary Byers, “New Evidence from Egypt on the Location of the Exodus Sea Crossing: Part I,” Associates for Biblical Research, August 19, 2008, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/exodus-era/3191-new-evidence-from-egypt-on-the-location-of-the-exodus-sea-crossing-part-i (accessed September 22, 2021).

36 Ibid.

37 James K. Hoffmeier, “Out of Egypt,” 17.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid. See also Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt; James K. Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

40 Joel Kramer, “The Oldest Yahweh Inscription,” Associates for Biblical Research, January 20, 2017, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/topics/egyptology/3541-the-oldest-yahweh-inscription (accessed September 22, 2021).

41 But consider the discovery announced by the Associates for Biblical Research of a Late Bronze lead curse tablet from Mt. Ebal that contains an inscription mentioning “Yahweh” twice. This discovery could be the oldest inscription that includes the name “Yahweh.” See https://biblearchaeology.org/research/topics/mt-ebal-curse-tablet-defixio/4902-a-note-from-dr-scott-stripling-on-shiloh-and-the-mt-ebal-discovery.

42 Charles Aling and Clyde Billington, “The Name Yahweh in Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts,” Associates for Biblical Research, March 8, 2010, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/exodus-era/3233-the-name-yahweh-in-egyptian-hieroglyphic-texts (accessed September 22, 2021).

43 Bryant G. Wood, “New Evidence Supporting the Early (Biblical) Date of the Exodus and Conquest,” Associates for Biblical Research, November 11, 2011, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/conquest-of-canaan/3518-new-evidence-supporting-the-early-biblical-date-of-the-exodus-and-conquest (accessed September 22, 2021).

44 Peter van der Veen, Christoffer Theis, and Manfred Gorg, “Israel in Canaan (Long) before Pharaoh Merenptah? A Fresh Look at Berlin Statue Pedestal Relief 21687,” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 2, no. 4 (2010): 16.

45 Ibid., 19.

46 Ibid., 21.

47 Gary Byers, “Great Discoveries in Biblical Archaeology: The Merneptah Stele,” Associates for Biblical Research, March 15, 2006, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/conquest-of-canaan/4024-great-discoveries-in-biblical-archaeology-the-merenptah-stela (accessed September 22, 2021).