The Bible indicates that many important Biblical characters spent time in Egypt: Abraham (Gn 12:10–13:1, Jacob (Gn 46–50), Joseph (Gn 39–50), Moses (Ex 2–12), Joshua, (Nm 14:26–30), Jeremiah (Jer 43:6–8) and even baby Jesus (Mt 2:14–21). Trade routes led from Canaan directly to the Nile delta region, where Goshen was located. Called Lower Egypt because the Nile flows from the mountains in the south (Upper Egypt) to the Mediterranean Sea in the north, this is the part of Egypt where most Biblical characters lived and Biblical events took place...

This article was first published in the Fall 2004 issue of Bible and Spade.

Yet many of the Egyptian leaders involved with these Biblical characters and events are best known from their temples and tombs in Upper (southern) Egypt. Statues and reliefs at the Karnak Temple and in the tombs and mortuary temples along both banks of the Nile tell the stories of these Egyptians. This article discusses the Bible as it is reflected at Karnak and other sites in Upper Egypt.

KARNAK

Waset was a small village on the Nile’s east bank, where the alluvial plain broadened out to about 9 mi. After the collapse of Egypt’s Old Kingdom (ca. 2687–2190 BC), it grew in size and influence until becoming the capital of reunited Egypt at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2060–1700 BC). It is better known in history by its ancient Greek name, Thebes. Long after the city declined, during the early Islamic period, the visible ruins of the Luxor Temple became known in Arabic as Al Uqsur (“The Palaces”). That name has come to us in its shortened version and is applied to the entire city—Luxor. The Karnak Temple complex, Egypt’s most famous temple, is within the city limits of modern Luxor.

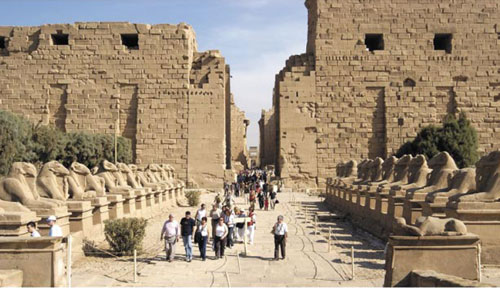

Entrance to the Karnak Temple. The temple was actually a complex, with multiple temples to a variety of Theban gods. The center of the complex was the Amun (and later Amun-re) Temple. It was the largest temple precinct and possibly the most important in ancient Egypt. While originally begun during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2060–1700 BC), it became a national building project during the New Kingdom (ca. 1570–1070 BC) and stayed under continual construction for some 1500 years, with subsequent Pharaohs adding on with pylons, shrines, obelisks and statues. Yet, none of these architectural features or decorations were designed for the masses to see and be impressed or educated by. Instead they were specifically designed to impress Amun (and possibly the powerful Amun priesthood, as well). Beyond the Amun Temple, the Karnak complex included a temple to Ptah (the creator god and patron of Memphis), a temple to Montu (the local war god) and a temple to Mut (Amun’s wife). Unlike most temples, which are built along a single axis, the Karnak Temple was built along two different axes, in all four directions of the compass.

Entrance to the Karnak Temple. The temple was actually a complex, with multiple temples to a variety of Theban gods. The center of the complex was the Amun (and later Amun-re) Temple. It was the largest temple precinct and possibly the most important in ancient Egypt. While originally begun during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2060–1700 BC), it became a national building project during the New Kingdom (ca. 1570–1070 BC) and stayed under continual construction for some 1500 years, with subsequent Pharaohs adding on with pylons, shrines, obelisks and statues. Yet, none of these architectural features or decorations were designed for the masses to see and be impressed or educated by. Instead they were specifically designed to impress Amun (and possibly the powerful Amun priesthood, as well). Beyond the Amun Temple, the Karnak complex included a temple to Ptah (the creator god and patron of Memphis), a temple to Montu (the local war god) and a temple to Mut (Amun’s wife). Unlike most temples, which are built along a single axis, the Karnak Temple was built along two different axes, in all four directions of the compass.

Michael Luddeni

The nucleus of the Karnak Temple as it is known today began with Sesostris I (founder of the Middle Kingdom’s 12th Dynasty). He apparently built a mud-brick royal chapel, no longer standing, for the local deity Amun (“the hidden one”) at a site where even earlier cultic structures sat along the Nile’s east bank. From there, later construction spread out along two axes, an unusual feature for Egyptian temples. Subsequent Pharaohs contributed to the complex with pylons, chapels, obelisks and statuary, sometimes even dismantling the work of earlier Pharaohs (Oakes and Gahlin 2003:154).

Later 12th and 13th Dynasty Pharaohs made the temple a repository for monuments, statues and treasures dedicated to the now combined god, “Amun-re...King of the Gods and who is over the Two Lands” (Redford 1992:442). During the following Hyksos period (the First Intermediate Period), the Karnak Temple fell into decline. But New Kingdom Pharaoh Thutmose I (18th Dynasty) from Thebes restored Amun-re’s Temple at Karnak, and Egypt’s rulers would continue to make additions for the next 1, 500 years. Amun-re had reached the status of national deity.

A canal from the Nile allowed ships to dock just outside the temple’s entrance, with remains of the landing stage still visible today. From here, a broad avenue, lined on both sides with ram-headed sphinxes, led to the front of the temple. Associated but disconnected temples to the north and south were the Montu (a local war god) Temple Enclosure and the Mut (wife of Amun) Temple Enclosure, respectively.

The avenue of sphinxes ended at the massive first pylon, the entrance into the Amun enclosure, much of what remains today. Behind the first pylon is the largest area of the complex, an open-air courtyard known as the Great Court. This would have been the only area of the temple commoners were allowed to see, and even then, only at occasional religious festivals. Here sit numerous structures and statues from various Pharaohs, including a single column and alabaster altar left from a cultic structure known as the Kiosk of Tirhakah (25th Cushite Dynasty; 2 Kgs 9:19; Is 19:9).

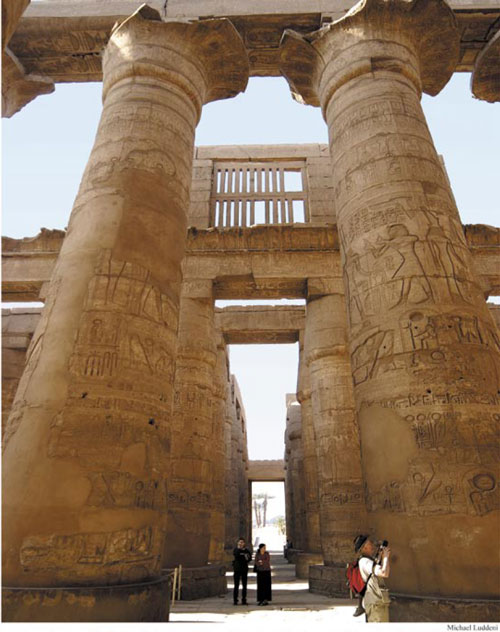

Within the Great Court, remnants of a mud-brick ramp can still be seen against the first pylon, offering some insight into ancient Egyptian construction techniques and engineering. To the east, the second pylon leads into the famous Hypostyle Hall, built by Seti I and decorated by Rameses II (19th Dynasty father-and- son Pharaohs). Massive sandstone blocks originally roofed the hall and stone-cut clerestory window provided the only light inside. This Hall is large enough to hold both Saint Peter’s Cathedral in Rome and Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London! Still standing today is a forest of 134 massive papyrus-shaped stone pillars which once held up the roof. It is an unforgettable sight!

Altogether the Amun Temple complex has eight pylons (massive gateways), many open-air courtyards, numerous roofed shrines and a sacred lake. Huge pillars, tall obelisks and Pharaonic statues are everywhere and almost every wall is carved in relief and painted with scenes from the reigns of various Pharaohs. Many of these scenes relate directly to the Biblical world.

Seti I’s (19th Dynasty) reliefs depict the “Way of the Philistines” that the Israelites did not take in the Exodus (Ex 13:17). Hatshepsut (18th Dynasty), daughter of one Pharaoh and wife of another, usurped the throne for 22 years and was possibly “Pharaoh’s daughter” that drew Moses out of the Nile (Ex 2:5–10; Hansen 2003). At Karnak, she constructed Egypt’s tallest obelisks (29.5 m; 96 ft), only one of which is still stands. In relief on the sixth and seventh pylons, Thutmose III (18th Dynasty) listed many cities in Palestine and Syria that he conquered (Redford 1992:442; Wilson 1969). Merenptah’s (19th Dynasty) relief, corresponding to the famous stele mentioning Israel found in his mortuary temple on the Nile’s west bank, is the earliest-known artistic representation of Israelites. The inscription of Shishak I (22d Dynasty) commemorated his invasion of Judah and Israel, as mentioned in the Bible (1 Kgs 14:25–26).

LUXOR

The village of Waset (ancient Thebes, modern Luxor) acquired an additional hieroglyphic name by the end of the New Kingdom. “The city of Amun” (niwt Amon), gave rise to the Biblical Hebrew name No' 'Amôn (Ez 30:14–16; Na 3:8), the Hebrew No’ coming from the hieroglyphic niwt, “city” (Redford 1992:442).

The once small village became the dominant city in southern (Upper) Egypt during the First Intermediate Period (ca. 2190–2060 BC). As the hometown to the now-ruling 11th Dynasty, Thebes became the new capital of reunited Egypt at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom. The Amun Temple at Karnak became a national religious center and added prestige to the city.

The 12th Dynasty, also from Upper (south) Egypt, was apparently unrelated to the previous line. While making deliberate connections to the Theban 11th Dynasty, this dynasty chose a new capital in Upper Egypt’s northern extremity, where the entire nation could be more effectively administrated and the eastern frontier could be better accessed (Leprohon 1992:345–46).

Still, the most powerful city in the south, Thebes, continued to serve as a national shrine with each Pharaoh bringing gifts to the Amun Temple at Karnak. Throughout the Second Intermediate Period, when the Asiatic Hyksos from the Delta ruled Egypt, Thebes continued to be the dominant city in Upper Egypt. A new Theban dynasty (the 18th) finally defeated the Hyksos and again reunited the nation.

While all New Kingdom Pharaohs were not Theban like the 18th Dynasty, they all treated Thebes as their royal hometown and necropolis. Admittedly they did seem to prefer residences in the north to administer their growing empire in Canaan to the east, but they continued to make their own mark on the national shrine at Karnak, the ever-growing Amun (now known as the combined god—Amun-re) Temple. Bringing vast quantities of booty from foreign wars, each Pharaoh made pilgrimages to Thebes for the annual Opet-festival (Redford 1992:442). During this ceremony, the images of Amun-re, Mut and Khonsu (the moon god) were transported up the Nile from Karnak to the newer Luxor Temple where Pharaoh would meet with the gods.

While royal palaces would have been constructed all around Thebes in antiquity, they have not yet been found. What we do know is that, at its height, Thebes was actually a series of settlements around major temples situated along broad sphinx-lined avenues on the Nile’s east bank. The central settlement lay in and around Karnak’s Amun-re Temple. To the north was the Montu temple and 1 km (0.6 mi) south was the complex to Mut (mother goddess) and Khonsu (her child). Another 3.5 km (2.2 mi) south was the Luxor Temple to Amun (Redford 1992:443). Communities of priests, builders, artisans and supporting industries made relatively self-sufficient settlements near each temple. Numerous prisoner-of-war slaves were employed in the state building projects in and around Thebes, including the Karnak Temple, the Pharaoh’s own Valley and Mortuary Temples, and the royal tomb. Many of these slaves were Asiatics from Canaan.

Massive columns of the Hypostyle hall in the Karnak Temple built in the early 13th century BC. Note the remnants of paint still visible on the under side of the capitals and stone roof beams. The hall is a dizzying forest of 134 papyrus-shaped columns. The columns of the two central rows that form the main aisle are a lofty 69 ft high and 34 ft in circumference. Remains of one of the stone-cut clerestory windows along the central aisle can be seen in the upper center. The capitals are so large that 125 men can stand on the top of one capital! On either side of the central aisle are seven rows of smaller columns 42–1/2 ft high and 27–1/2 ft in circumference.

Massive columns of the Hypostyle hall in the Karnak Temple built in the early 13th century BC. Note the remnants of paint still visible on the under side of the capitals and stone roof beams. The hall is a dizzying forest of 134 papyrus-shaped columns. The columns of the two central rows that form the main aisle are a lofty 69 ft high and 34 ft in circumference. Remains of one of the stone-cut clerestory windows along the central aisle can be seen in the upper center. The capitals are so large that 125 men can stand on the top of one capital! On either side of the central aisle are seven rows of smaller columns 42–1/2 ft high and 27–1/2 ft in circumference.

Michael Luddeni

LUXOR TEMPLE

Connected to the Karnak Temple by a 3.2 km (2 mi) long sphinx-lined avenue was a later temple known as the Luxor Temple. Very near the Nile’s east bank, the earliest religious structures were shrines built by Hatshepsut (18th Dynasty) to the Theban triad of Amun-re (the husband/father god), Mut (the wife/mother goddess; the goddess of war) and Khonsu (their divine offspring; the moon god). They still can be seen today within the Peristyle Court.

Amenhotep III (18th Dynasty) greatly enlarged the temple as Amun’s private quarters, including the Great Colonnade and the Court of Amenhotep III behind it with its double rows of massive columns. Much of this still can be seen today. The Luxor Temple was the focus of the annual ophet-festival. Later additions were made by Tutankhamun (18th Dynasty), Rameses II (19th Dynasty) and Alexander the Great (who redesigned the main sanctuary). During the Roman period, the Temple was rededicated to the imperial cult and even an altar was found dedicated to Emperor Constantine (fourth century AD).

During the 19th century, the Mosque of Abu el-Hagag was built within the ruins of the Luxor Temple. Until excavations of the temple began in 1885, a village was located inside the temple walls. Within the Inner Sanctum was a suite of rooms, the “bedroom” of the god, where the secret rites of the opet-festival took place (Oakes and Gahlin 2003:152–53). The boats, which floated down the Nile with the images of the gods, were carried into this area for the culmination of the festival.

The first pylon was constructed by Rameses II (19th Dynasty) and recorded his military exploits against the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh (1275 BC). He further decorated the entranceway with six statues of himself (two seated and four standing) and two obelisks.

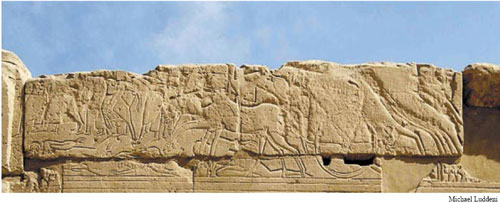

Along the secondary north-south axis of Karnak Temple is a relief carved by Merenptah (1212–1202 BC) that apparently corresponds to the famous stele found in his mortuary temple on the west bank (Byers 2004). In an area between the Hypostyle Hall and the seventh pylon at Karnak Temple, known as the Cour de la Cachette, Merenptah depicted military exploits from his Canaanite campaign in 1210 BC. This wall, originally about 49 m (160 ft) long and 9 m (30 ft) high, was constructed by Ramesses II and already contained the text of his Battle of Kadesh (1275 BC) peace treaty with the Hittites. Merenptah usurped space on both sides of the treaty text to illustrate his Canaanite campaign. Interestingly, he did the same thing with the stele on which is recorded in text form this same military action. After demolishing Pharaoh Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple to build his own, Merenptah appropriated and reused the reverse side of a 3 m (10 ft) tall stone monument originally carved by Amenhotep III. In the Karnak Temple, three cities are depicted being conquered by the Pharaoh. One of them, Ashkelon, is named and apparently the other two are Gezer and Yenoam, as described in Merenptah’s stele. The fourth scene, above and to the right of Ramesses’ peace treaty, did not depict a city but a people group being defeated—also described in the stele. They appear as a confusing jumble of defeated soldiers beneath the horses of Merenptah’s chariot. Like the people in the conquered cities, these soldiers wear ankle-length garments, suggesting they inhabit the same region. Apparently these soldiers were the fourth defeated enemy in Merenptah’s Canaan campaign—Israel—just as recorded in the Merenptah Stele. That makes this the earliest visual portrayal of Israelites ever discovered. The next time Israelites are visually depicted on a relief comes ca. 370 years later on an Assyrian obelisk (Maier 2004:91).

Along the secondary north-south axis of Karnak Temple is a relief carved by Merenptah (1212–1202 BC) that apparently corresponds to the famous stele found in his mortuary temple on the west bank (Byers 2004). In an area between the Hypostyle Hall and the seventh pylon at Karnak Temple, known as the Cour de la Cachette, Merenptah depicted military exploits from his Canaanite campaign in 1210 BC. This wall, originally about 49 m (160 ft) long and 9 m (30 ft) high, was constructed by Ramesses II and already contained the text of his Battle of Kadesh (1275 BC) peace treaty with the Hittites. Merenptah usurped space on both sides of the treaty text to illustrate his Canaanite campaign. Interestingly, he did the same thing with the stele on which is recorded in text form this same military action. After demolishing Pharaoh Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple to build his own, Merenptah appropriated and reused the reverse side of a 3 m (10 ft) tall stone monument originally carved by Amenhotep III. In the Karnak Temple, three cities are depicted being conquered by the Pharaoh. One of them, Ashkelon, is named and apparently the other two are Gezer and Yenoam, as described in Merenptah’s stele. The fourth scene, above and to the right of Ramesses’ peace treaty, did not depict a city but a people group being defeated—also described in the stele. They appear as a confusing jumble of defeated soldiers beneath the horses of Merenptah’s chariot. Like the people in the conquered cities, these soldiers wear ankle-length garments, suggesting they inhabit the same region. Apparently these soldiers were the fourth defeated enemy in Merenptah’s Canaan campaign—Israel—just as recorded in the Merenptah Stele. That makes this the earliest visual portrayal of Israelites ever discovered. The next time Israelites are visually depicted on a relief comes ca. 370 years later on an Assyrian obelisk (Maier 2004:91).

Michael Luddeni

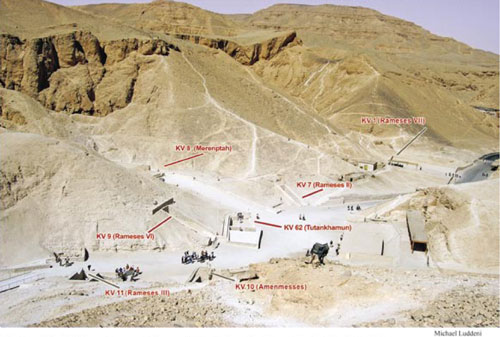

VALLEY OF THE KINGS

While the Nile’s east bank was given over to palaces and temples and their surrounding settlements, the west bank was a vast necropolis, both royal and private, within the desert mountain region. Beyond Pharaonic tombs in the Valley of the Kings was the Valley of the Queens, the Valley of the Nobles and even the necropolis (and village) of the Valley of the Kings’ workers, at Deir el Medina (Hawass 1997:287). As was customary throughout dynastic Egypt, the royal necropolis was located near the capital. In Old Kingdom Egypt, when the capital was at Memphis, Pharaohs built their mortuary temples and pyramid tombs at Dahshur, Saqqara, Abu Sir and Giza. When Thebes became Egypt’s capital during the 11th Dynasty, Pharaoh Montuhotpe I constructed his mortuary temple and tomb in a valley on the Nile’s west bank, across from Thebes.

Later Middle Kingdom Pharaohs also built pyramid tombs, now of mud brick, near the northern capital, itj-tawy. While the exact location is unknown today, it was no doubt near the royal Middle Kingdom cemetery at modern El Lahun (Leprohon 1992:346). But with the 18th Dynasty reuniting Egypt at the beginning of the New Kingdom, Thebes was reestablished as a capital city. The new royal cemetery was in the mountains across from Thebes.

In the desert directly across from Thebes each Pharaoh had his own Valley Temple constructed at the end of a canal dug from the Nile. Here the royal body was received from Thebes by way of the royal funeral barque. The body was then transported to the Pharaoh’s specially constructed mortuary temple in preparation for his burial. All this continued as a 1500-year-long Pharaonic practice. But New Kingdom tombs were no longer constructed as pyramids. Instead, their tombs were horizontal shafts cut through solid rock, often hundreds of meters deep in the mountainside.

The mortuary temples were surrounded by settlements of builders, artisans and priests. Still seen today (from south to north) are the mortuary temples of: Rameses III at Medinet Habu, Amenhotep III, the Ramesseum (mortuary temple) of Rameses II, the Deir el-Bahri complex with the mortuary temples of Middle Kingdom Pharaoh Montuhotpe I and Queen Hatshepsut, and the temple of Seti I (Redford 1992:443). Constructed during Egypt’s New Kingdom (ca. 1570–1070 BC), the Luxor Temple had all the features typical for that period. As a “god’s house,” a temple was constructed along the same lines as the home of a wealthy Egyptian of the time. There was an open-to-the-sky courtyard directly inside the front gate, where the homeowner might meet with visitors. While some temples may have more than one open-air forecourt, this was the only part of an ancient temple the common people could ever visit, and, even then, only on appropriate religious festivals. Behind the temple’s open court was a high-roofed hall with rows of interior pillars to hold up the roof. Windows were high on the roof in clerestory fashion. This corresponded to the front of the private part of a house. At the back of the house would be the house’s most private area—the occupants’ bedrooms. Here was the inner sanctum of the typical Temple—where the image of the god dwelt. Only the king, in his capacity as high priest, and other important functionaries, would have been allowed to enter these chambers. The Luxor Temple was considered the private quarters for the patron god of Thebes, Amun. The statue of Amun would annually be brought up the Nile to stay in his special place and here he would have private meetings in his innermost chambers with the reigning Pharaoh.

Constructed during Egypt’s New Kingdom (ca. 1570–1070 BC), the Luxor Temple had all the features typical for that period. As a “god’s house,” a temple was constructed along the same lines as the home of a wealthy Egyptian of the time. There was an open-to-the-sky courtyard directly inside the front gate, where the homeowner might meet with visitors. While some temples may have more than one open-air forecourt, this was the only part of an ancient temple the common people could ever visit, and, even then, only on appropriate religious festivals. Behind the temple’s open court was a high-roofed hall with rows of interior pillars to hold up the roof. Windows were high on the roof in clerestory fashion. This corresponded to the front of the private part of a house. At the back of the house would be the house’s most private area—the occupants’ bedrooms. Here was the inner sanctum of the typical Temple—where the image of the god dwelt. Only the king, in his capacity as high priest, and other important functionaries, would have been allowed to enter these chambers. The Luxor Temple was considered the private quarters for the patron god of Thebes, Amun. The statue of Amun would annually be brought up the Nile to stay in his special place and here he would have private meetings in his innermost chambers with the reigning Pharaoh.

Michael Luddeni

Beginning with Thutmosis I (18th Dynasty) and extending through the end of the 20th Dynasty, Pharaohs were buried in their New Kingdom-style tombs in what we call the Valley of the Kings (Redford 1992:442). Here you can visit the tombs of numerous Pharaohs who had an impact on the Biblical story. Tuthmosis III (KV 34) was possibly the Pharaoh of the Oppression (Ex 1–2) with Amenhotep II (KV 35) possibly the Pharaoh of the Exodus (Ex 5–12). Here, too, is Rameses II (KV 7), whose reliefs show his campaigns into Syro-Palestine, and the tomb of his 52 sons (KV 5), the largest tomb in the valley. Merenptah, in KV 8, created the monument with Egypt’s only Old Testament era reference to Israel and the earliest mention anywhere outside the Bible. Rameses III (KV 11), who defeated the Philistines and other Sea Peoples, is also buried in the valley. Here, too, is the famous tomb of King Tut (KV 62), who ruled Egypt as a teenager during the Biblical period of the Judges.

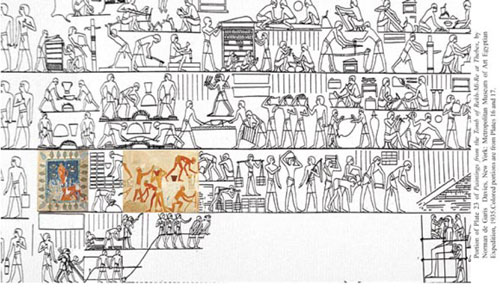

Also on the Nile’s west bank were the tombs of the nobles. Not being royalty, they could not be buried within the Valley of Kings, the resting place of the Pharaohs they served. Within these tombs are colorful paintings of significant events in their lives. From Mena’s tomb (ca. 1385 BC) was a grain harvest scene that helps us imagine the seven years of plenty from Joseph’s time (Gn 41:47–49). The Tomb of Userhat (ca. 1280 BC) shows barbers cutting hair, also reminiscent of the Joseph story (Gn 41:14). From the Tomb of the Vizier Rekhmire (ca. 1470–1445 BC) is a brick-making and building scene depicting Asiatics from the actual period of the Israelites bondage (Ex 1:11–14; 5:7–19).

While these private tombs were decorated with colorful and lively paintings of daily life, Pharaonic tombs and mortuary temples were covered with carved and painted reliefs depicting scenes from magical-religious texts. Known as the Book of the Dead, the Book of Gates and the Book of What is in the Underworld, these scenes were considered essential for Pharaoh’s connection with the godhead in the afterlife (Hawass 1997:287). These elaborate tombs, which, at times, nearly bankrupted the nation, show what lengths the Pharaohs would go to be ready for the afterlife.

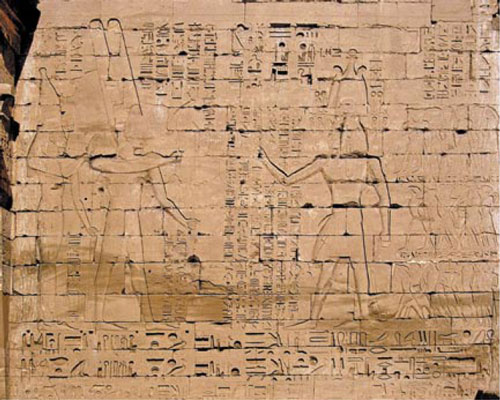

Ramesses III’s (ca. 1184–1153 BC) mortuary temple at Medinet Habu was inspired by the Ramesseum, the mortuary temple of Ramesses II (ca. 1279–1212 BC). Medinet Habu, on the Nile’s west bank, is the name of the village that later developed within the temple complex. Typical of Pharaonic mortuary temples, outside the complex’s eastern gate was once the landing quay for a canal from the Nile. This gate, known today as the “Syrian Gate,” is a large two-story structure modeled after a Canaanite migdol (“fortress”). On walls and pillars within the temple’s frontcourt, different Sea People groups are depicted in relief; including Sardinians, Daneans and Philistines. In the scene shown here, on the second pylon, Ramesses III presents Sea Peoples captives to the god Amun. Interestingly, Sardinians with their horned helmets and Philistines wearing distinctive “feathered” helmets are depicted as both mercenary soldiers serving under Ramesses III and as his captives. On the outer side of the temple’s northern wall, a series of seven scenes depicts Ramesses III in his war with the “Peoples of the Sea” from the eighth year of his reign. Viewed in order from east to west, Sardinians are first seen as mercenaries with the Egyptian infantry, but further along other Sardinians are seen fighting against the Egyptians in a sea battle. Philistines are depicted here only as an enemy, on land and sea. Also depicted are two-wheeled ox carts with Philistine families waiting nearby. Later scenes depict defeated Philistine soldiers among Egypt’s prisoners. During the same period that Ramesses III depicted Philistines living as families in the region, the Bible indicates they lived in Canaan. This is the time of the Judges, and while the Bible doesn’t mention “Sea People,” it does describe the settlement of one of their tribes, the Philistines, along the southern Mediterranean coastline. The Bible is precise and accurate in its depiction of the Philistines—in both time and place.

Michael Luddeni Constructed at the base of a pyramidal mountain in the desert on the west bank of the Nile is the famous necropolis (Greek “dead/city” or “city of the dead”) for Pharaohs of Egypt’s New Kingdom (ca. 1570–1070 BC). With Thebes as their capital and hometown, the dead bodies of New Kingdom Pharaohs were transported across the Nile on boats to their own specially constructed, but small, Valley Temple on the west. From here they were transported to their much more impressive Mortuary Temple in the desert, where they were prepared for burial. These structures were constructed outside the area of the Nile floodwaters, to maximize arable land as well as to keep the temples from continually suffering water damage. Today, with the Aswan Dam, the Nile does not flood annually as it did for millennia. After preparation of the body, the Pharaonic mummy was transported to his “secret” tomb within the not-easily-accessible Valley of the Kings. Unfortunately, tomb builders and funerary workers knew exactly were the tomb and its treasures were located and every ancient royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings has been entered. Even King Tut’s tomb had been broken into, but had been resealed with minimal damage. It was subsequently buried and lost until 1922.

Constructed at the base of a pyramidal mountain in the desert on the west bank of the Nile is the famous necropolis (Greek “dead/city” or “city of the dead”) for Pharaohs of Egypt’s New Kingdom (ca. 1570–1070 BC). With Thebes as their capital and hometown, the dead bodies of New Kingdom Pharaohs were transported across the Nile on boats to their own specially constructed, but small, Valley Temple on the west. From here they were transported to their much more impressive Mortuary Temple in the desert, where they were prepared for burial. These structures were constructed outside the area of the Nile floodwaters, to maximize arable land as well as to keep the temples from continually suffering water damage. Today, with the Aswan Dam, the Nile does not flood annually as it did for millennia. After preparation of the body, the Pharaonic mummy was transported to his “secret” tomb within the not-easily-accessible Valley of the Kings. Unfortunately, tomb builders and funerary workers knew exactly were the tomb and its treasures were located and every ancient royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings has been entered. Even King Tut’s tomb had been broken into, but had been resealed with minimal damage. It was subsequently buried and lost until 1922.

Michael Luddeni

JOSEPH IN UPPER EGYPT

In a six-part series of articles on the life of Joseph in Bible and Spade, Professor Charles Aling suggested that Joseph probably spent significant time in Upper (southern) Egypt. Interestingly, Israel’s Egyptian sojourn centered at Goshen in the delta region of Lower (northern) Egypt early in the Middle Kingdom. Egypt’s institution of slavery also appeared in the delta area during the Middle Kingdom (Aling 2002a: 23; 2002b: 35).

Numerous Egyptian documents from that period indicate that many Asiatics lived and worked as slaves throughout the Nile Valley. While there were no major military campaigns into Syro-Palestine at this time, recent Middle Kingdom documents indicate these Asiatic slaves arrived in Egypt as prisoners-of-war, as tribute from officials elsewhere and through trade or purchase (Kitchen 2003:2).

Some slaves were pressed into government service, some served the temples, and some were owned by wealthy officials (Kitchen 2003:2). Potiphar, a government official, purchased an Asiatic slave named Joseph from a Midianite caravan (Gn 37:36; 39:1), presumably to work on his estate in the delta region. The Brooklyn Papyrus from the Middle Kingdom period mentions “household slaves” and “stewards” (Hayes 1972), both positions held by Joseph in Potiphar’s house (Gn 39:4, 17; see Aling 2002b: 35, 37).

After the accusation of Potiphar’s wife, Joseph was cast into prison (Gn 39:20). Interestingly, Egypt was one of the few nations in the ancient world to have prisons, in the classical use of the term. Since adultery was a capital offense in Egypt, the fact that Joseph was only confined to prison seems to indicate that Potiphar did not necessarily believe the accusation. Nothing is known about the length of sentences in ancient Egypt, but those not put to death were probably given life sentences. Yet, there might be a period of confinement for those waiting a decision, like the Chief Butler and Baker (Aling 2002c: 99). Joseph may have had a life sentence.

The Brooklyn Papyrus also speaks about Middle Kingdom Egypt’s institution of prisons and indicates that the main prison—the “Place of Confinement”—was located at Thebes. Joseph was imprisoned with two of Pharaoh’s personal officials (Ex 39:20; 40:3), and it is reasonable to believe this was at Thebes. Twelfth Dynasty Pharaohs from Upper (southern) Egypt established their capital at Itj-tawy, near modern Lisht, in Upper Egypt’s northern border (Ray 2004:40) and this was probably the capital in Joseph’s day.

After interpreting Pharaoh’s dream, Joseph was rewarded by Pharaoh with three titles (Gn 45:8). Two of them suggest Joseph had responsibilities that would have required him to spend significant time in Upper (southern) Egypt. His title “Father to Pharaoh” (Hebrew), but understood as “Father of the God” to the Egyptians, had minimal implications on where he worked. But his second title, “Lord of all Pharaoh’s House” (Hebrew), corresponded to the Egyptian “Chief Steward of the King.” Egyptian documents from the period indicate this involved supervision of royal agricultural estates and granaries. Some, of necessity, would have been around the most important city of Upper Egypt—Thebes (Aling 2003:58–59).

Joseph’s third title, “Ruler of all Egypt” (Hebrew), corresponded to the most important position under Pharaoh in ancient Egypt—”Vizier.” Later New Kingdom texts indicate the Vizier supervised the government in general, was the government’s chief record keeper, appointed lower officials, controlled access to Pharaoh, welcomed foreign emissaries, oversaw agricultural production and supervised construction and industry in Egypt’s state-run economy (Aling 2003:60–61). Beyond overseeing Pharaoh’s own holdings, Joseph’s official responsibilities would have necessitated considerable time in Upper Egypt, especially during the seven years of plenty and seven years of famine.

Joseph was age 30 when he was freed from prison and promoted to high office by Pharaoh (Gn 41:46). Biblical and Egyptian chronologies suggest the Pharaoh who promoted Joseph was Sesostris II (1897–1877 BC). If this is correct, the seven years of plenty were probably the final seven years of his reign (Aling 1997a: 19). During these years, Joseph would have traveled extensively overseeing agricultural harvest and storage as well as government construction projects. This, no doubt, included supervising preparation of Pharaoh’s own pyramid tomb and burial at El Lahun in Upper Egypt.

The seven years of famine would then have been the first seven years of the Pharaoh’s son, Sesostris III (1878–1843). Interestingly, royal records indicate he waited until the eighth year of his reign to fight his first foreign campaign (Aling 1997a: 19). Sesostris III’s administration was known for three aspects: his foreign policy, his military and other building projects and internal reforms. As Vizier, Joseph would have had responsibilities in each realm and would have been active all over Upper Egypt (Gn 41:46), as far south as the Nubian border (Aling 1997b: 20–21).

Mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut (ca. 1503–1483 BC). Hatshepsut was the daughter of Tuthmosis I and his primary wife, Queen Ahmose. Tuthmosis II, son of Tuthmosis I and a secondary wife, became the next Pharaoh. To legitimize Tuthmosis II’s religious right to the throne according to early 18th Dynasty custom, he married his half-sister, Hatshepsut. Tuthmosis II and Hatshepsut had no son, but he had a son by a secondary wife—his name would be Tuthmosis III and he was to be the next Pharaoh. When Tuthmosis II died, his son was apparently so young that his aunt (step-mother!) took charge and reigned as co-regent with her young stepson. This co-regency lasted for 22 years (Hansen 2003:16). She may well be “Pharaoh’s daughter” who drew Moses out of the Nile (Hansen 2003:19).

Mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut (ca. 1503–1483 BC). Hatshepsut was the daughter of Tuthmosis I and his primary wife, Queen Ahmose. Tuthmosis II, son of Tuthmosis I and a secondary wife, became the next Pharaoh. To legitimize Tuthmosis II’s religious right to the throne according to early 18th Dynasty custom, he married his half-sister, Hatshepsut. Tuthmosis II and Hatshepsut had no son, but he had a son by a secondary wife—his name would be Tuthmosis III and he was to be the next Pharaoh. When Tuthmosis II died, his son was apparently so young that his aunt (step-mother!) took charge and reigned as co-regent with her young stepson. This co-regency lasted for 22 years (Hansen 2003:16). She may well be “Pharaoh’s daughter” who drew Moses out of the Nile (Hansen 2003:19).

Sesostris III’s own pyramid tomb in Dahshur (northern Upper Egypt) was no doubt a major responsibility for Joseph. For the record, later Viziers in the reign of Sesostris III are mentioned in surviving documents, suggesting Joseph probably went into honorable retirement to live in Goshen of Lower (northern) Egypt (Aling 1997b: 21; Wood 1997:55). Interestingly, only after Joseph’s day do Egyptian documents indicate that the titles Vizier and Chief Steward were given to the same man. It is possible that Joseph was the first to hold both (Aling 2003:61).

CONCLUSION

Much of what we know about Egypt’s New Kingdom Pharaohs comes from their statuary and reliefs carved at the Karnak Temple and their mortuary temples and tombs across the river. It is worth emphasizing that the Karnak Temple was not constructed as a public monument designed to teach living object lessons to the citizens of Egypt. Average people were not allowed inside the Temple complex. Consequently every architectural feature, however massive or beautiful, was designed by each Pharaoh to impress his god; and, possibly, to keep the very powerful priesthood as good allies.

The same can be said about each Pharaoh’s tomb and mortuary temple. The amazing artwork was not created for people to see. A Pharaoh’s entire reign was devoted to preparing for the afterlife, and he invested untold wealth on his eternal destiny. The tomb was to be sealed and no one was to enter again. The Pharaohs would be appalled by the mass of tourists daily visiting their private tombs!

So it is no surprise that every stone-carved text and relief within the Karnak temple complex lists a Pharaoh’s accomplishments and his expressed gratitude to the gods for making it all possible. There are no defeats recorded here and even victories are often overstated. Probably the classic example is Merenptah’s boast of the destruction of Israel. While his mention of Israel is a very important historical reference, he was absolutely wrong about Israel’s demise. They continued to live in and control their region for the next 600 years.

Egyptology has demonstrated that Pharaohs often altered earlier reliefs to change the historical record. It appears that early 18th Dynasty Pharaohs destroyed the textual evidence for the Hyksos ruling in Egypt. The attempt by Tuthmosis III to erase Hatshepsut from all her monuments is a classic example (Dalman 2003:53). Thus, as we endeavor to reconstruct ancient Egyptian history, it is important to remember that the best, and often only, texts we have are simply each Pharaoh’s best effort at public relations and political spin, regardless of the facts! Either way, archaeological evidence throughout Upper Egypt, from the Karnak Temple to the Valley of the Kings, demonstrates the Bible’s accurate portrayal of ancient Egypt.

From the rock-cut tomb of Rekhmire in the Valley of the Nobles comes this scene of Asiatics making bricks for the workshops of the Karnak Temple (second register from the bottom). An accompanying inscription says the workmen are prisoners of war from Nubia and Syro-Palestine, identified by their black and yellow skin color respectively. National labor projects by POWs were a regular practice in New Kingdom Egypt. Rekhmire (ca. 1470–1445 BC) lived in Thebes at the time Moses was in exile in Midian. The scene is reminiscent of Exodus 1:14, “they made their lives bitter with hard labor in brick and mortar.” Rekhmire’s title was Vizier to Thutmosis III, a position similar to that held by Joseph under Sesostris II. At the left, workers fill jars with water from a tree-lined pool. The water is added to piles of clay on the lower left. A worker with a hoe breaks up the clay, while another kneads the moistened clay with his feet. Baskets of wet clay are passed to brick makers above the clay preparation area. They form bricks with molds and leave the bricks to dry in the sun. Hardened bricks are being carried off to the building project to the right. Note the seated and standing Egyptian taskmasters on the right, both wielding rods. While it should not be assumed that the scene depicts Israelites, the parallels to the Biblical story are striking and demonstrate how accurately the Bible portrays the Israelite sojourn in Egypt.

From the rock-cut tomb of Rekhmire in the Valley of the Nobles comes this scene of Asiatics making bricks for the workshops of the Karnak Temple (second register from the bottom). An accompanying inscription says the workmen are prisoners of war from Nubia and Syro-Palestine, identified by their black and yellow skin color respectively. National labor projects by POWs were a regular practice in New Kingdom Egypt. Rekhmire (ca. 1470–1445 BC) lived in Thebes at the time Moses was in exile in Midian. The scene is reminiscent of Exodus 1:14, “they made their lives bitter with hard labor in brick and mortar.” Rekhmire’s title was Vizier to Thutmosis III, a position similar to that held by Joseph under Sesostris II. At the left, workers fill jars with water from a tree-lined pool. The water is added to piles of clay on the lower left. A worker with a hoe breaks up the clay, while another kneads the moistened clay with his feet. Baskets of wet clay are passed to brick makers above the clay preparation area. They form bricks with molds and leave the bricks to dry in the sun. Hardened bricks are being carried off to the building project to the right. Note the seated and standing Egyptian taskmasters on the right, both wielding rods. While it should not be assumed that the scene depicts Israelites, the parallels to the Biblical story are striking and demonstrate how accurately the Bible portrays the Israelite sojourn in Egypt.

Bibliography

Aling, Charles. 1997a Pharaohs of the Bible Part III: Joseph and the Pharaoh. Artifax 12.1:8–19.

Aling, Charles. 1997b Pharaohs of the Bible Part IV: Joseph and Sesostris III. Artifax 12.2:20–21.

Aling, Charles. 2002a Joseph in Egypt. Bible and Spade 15:21–23.

Aling, Charles. 2002b Joseph in Egypt, Part 2. Bible and Spade 15:35–38.

Aling, Charles. 2002c Joseph in Egypt, Part 3. Bible and Spade 15:99–101.

Aling, Charles. 2003 Joseph in Egypt, Part 4. Bible and Spade 16:10–13.

Byers, Gary A. 2004 Great Discoveries in Bible Archaeology: The Merneptah Stela. Bible and Spade 19:96.

Dalman, R. W. 2003 Captives of Amenhotep II. Bible and Spade 16:52–53.

Hansen, David. 2003 Moses and Hatshepsut. Bible and Spade 16:14–20.

Hawass, Zahi. 1997 Upper Egypt. Pp. 286–88 in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East 5, ed. Eric M. Meyers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hayes, William C. 1972 A Papyrus of the Late Middle Kingdom in the Brooklyn Museum. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum Reprint.

Kitchen, Kenneth A. 2003 The Joseph Narrative (Gen 37, 39–50). Bible and Spade 16:2–9.

Leprohon, Ronald J. 1992 Egypt, History of: Middle Kingdom—2D Intermediate Period (DYN. 11–17). Pp. 345–48 in The Anchor Bible Dictionary 2, ed. David N. Freedman. New York: Doubleday.

Maier, Paul L. 2004 Archaeology—Biblical Ally or Adversary? Bible and Spade 17:83–95.

Oakes, Lorna, and Gahlin, Lucia. 2003 Ancient Egypt. New York: Barnes and Noble.

Ray, Paul J., Jr. 2004 The Duration of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt. Bible and Spade 17:33–44.

Redford, Donald B. 1992 Thebes. Pp. 442–43 in The Anchor Bible Dictionary 6, ed. David N. Freedman. New York: Doubleday.

Wilson, John A. 1969 Lists of Asiatic Countries Under the Egyptian Empire. Pp. 242–43 in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, ed. James B. Pritchard. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wood, Bryant G. 1977 The Sons of Jacob. Bible and Spade 10:53–65.