A New Discovery at Persepolis

Parsa, the magnificent ceremonial city of the Persian Empire, is not known in history by its Persian name but by what the Greeks who plundered it and burned it to the ground called it: Persepolis. Probably having had much of its records destroyed in this fire, the Persian Empire is largely unknown today even though it once ruled most of the ancient known world.

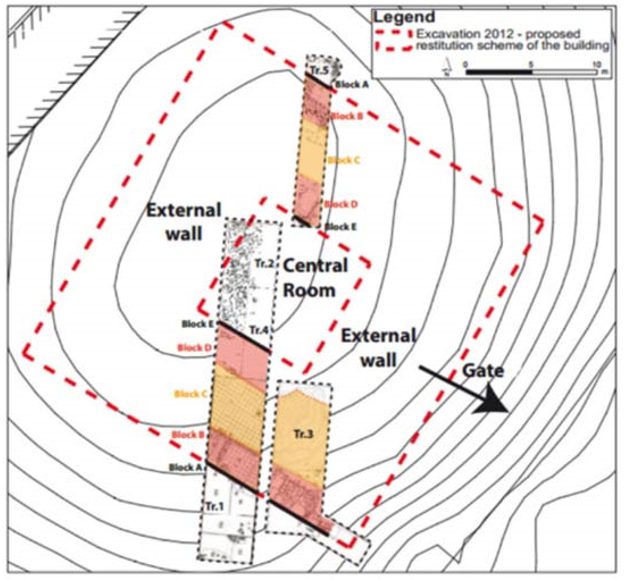

A team of Iranian and Italian archaeologists as well as cultural heritage experts began excavations at Tall-e-Ajori near Persepolis in 2011 led by Iranian archaeologist Alireza Askari-Charhoudi from the University of Shiraz and Italian archaeologist Pierfrancesco Callieri from the University of Bologna. In late 2020, the chief Iranian archaeologist announced that a massive ornamental gateway had been uncovered measuring 30 by 40 meters to a height of about 12 meters with a rectangular room in the center. The body and façade of the walls are adorned with colored panels made of brick with its exterior decorated with various mythical animals and belief symbols of ancient Iranians, Elamites, and Mesopotamians. The lower parts and the base that supports the walls are decorated with lotus flowers. Cuneiform inscriptions in Babylonian and Elamite were uncovered in the corridor that passed through the center of the gateway. Such news involving Persepolis could have significant historical importance.

The Historical Significance of Cyrus

The founder of the Persian Empire, Cyrus, began as king of the vassal province of the Medes called Pars (or Fars) located along the northern coast of the Persian Gulf. When he died in 530 BC, his empire extended through modern-day Turkey and the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, eastward to the Indus River and the border of India.

While Persia often gets overlooked historically, Cyrus the Great, on the other hand, is one of history’s most admired kings. The way that he chose to rule was widely respected during his reign as well as by later rulers who learned from his example. Showing respect for the people in the aftermath of his conquests, Cyrus realized that such an immense empire of diverse ethnicities, languages, religions, and cultures needed political and cultural flexibility. The result was a system that delegated power into the hands of satraps or governors over each of the provinces of the empire. As long as they maintained their loyalty and brought their annual financial offerings to the king’s treasury, satraps could exercise broad powers to administer their provinces generally unhindered.

Placing more emphasis on political and cultural stability through effective administrative and political skills rather than brute power, Cyrus is unique in history for the treatment of those who came under his control. After defeating Babylon and Lydia, these captured kingdoms were not burned and neither did he execute the survivors or sell them into slavery as did conquerors of his day. Instead, these kingdoms were treated as being “under new management” causing Cyrus to be viewed as a liberator and not as a tyrant, especially as he also abolished slavery throughout the empire and allowed the people to observe their religions and other customs unhindered.

While there is no conclusive evidence to make a definitive statement, the discovery of this ornamental gateway has, nevertheless, created speculation that it may have existed at the time of Cyrus and may have stimulated the building of Persepolis itself.

In Jewish Antiquities, the historian, Josephus, described how the neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar had earlier burned Jerusalem, destroyed the temple, and dismantled the city wall. After Cyrus defeated Babylon, Jewish leaders informed him that Nebuchadnezzar had also forcibly exported a large portion of Jerusalem’s population to Babylon. Indicating that they wished to return, these leaders showed him the book of Isaiah written over a century before Cyrus was born, pointing out numerous passages that mentioned Cyrus by name.

This is what the Lord says to his anointed, to Cyrus, whose right hand I take hold of to subdue nations before him and to strip kings of their armor, to open doors before him …. I summon you by name and bestow on you a title of honor though you do not acknowledge me …. I will raise up Cyrus in my righteousness: I will make all his ways straight. He will rebuild my city and set my exiles free.

Stirred by Isaiah’s favorable references from the book of Isaiah about him, Josephus described how Cyrus ended the 70-year captivity of the Jews in Babylon, allowing them to return home to rebuild Jerusalem, its temple, and the city walls. In addition, Cyrus decreed that the gold and silver vessels of worship at the temple that had been confiscated by Nebuchadnezzar were to be removed from the treasury in Babylon and returned to Jerusalem.

Religious and cultural motifs that decorate the gateway have similarities to those found at the Ishtar Gateway at Babylon.

The Rise and Fall of the Achaemenids

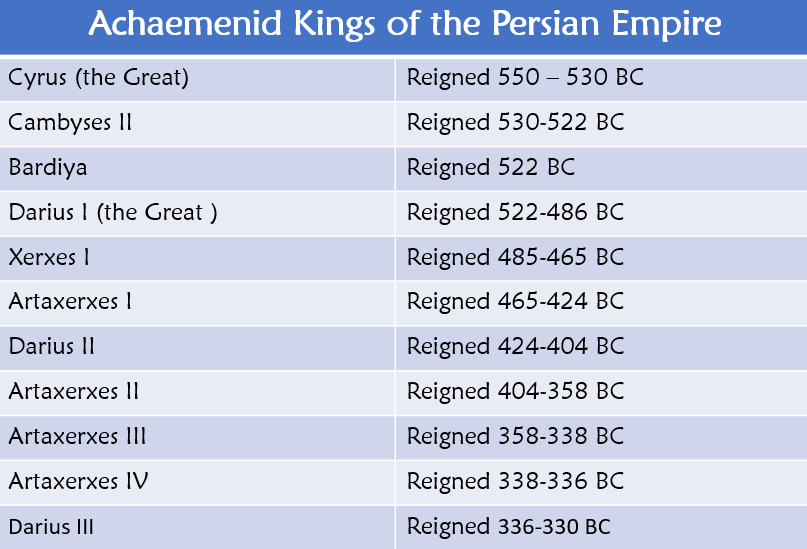

Ruling from 550 BC to 329 BC, Cyrus and the ten Persian rulers who followed were collectively known as the Achaemenids, a family based in Pasargadae in Pars. Cyrus established the independence of Pars by overthrowing their Mede overlords in 550 BC and defeating Lydia in western Asia Minor in 547 BC. Cyrus then put an end to the neo-Babylonian empire in 539 BC. In 525 BC, the successor of Cyrus, Cambyses, added Egypt to the empire while two other successors of Cyrus would unsuccessfully try to add Greece as well, provoking two of the most famous wars in ancient history. Led by Darius the Great, the Persians first attacked Greece in 492 BC before being repelled in 490 BC. In a second, even more massive invasion, Xerxes attacked Greece in 480-479 BC, managing to capture Athens, set it on fire, but eventually having to withdraw after losing the decisive naval battle at Salamis.

As the empire expanded, construction began on a monumental city named Parsa (the city of Pars) about 40 miles south of Pasargadae, where Cyrus had reigned. Construction of a new ceremonial, rather than political, capital of the empire is attributed to Darius the Great in 515 BC. Parsa truly became the showcase city for the Achaemenids as Xerxes and other successors made Parsa the treasury city of the empire to demonstrate the power and majesty of the Persians. Satraps, dignitaries, and representatives of their vassal provinces required to bring their annual tribute to Parsa were dazzled as they witnessed the city’s magnitude, beauty, and wealth.

Meanwhile, the two wars with Persia had promoted greater unity among the Greeks and had also motivated them to become a first-class military power. A century and a half later, after subduing his opposition within Greece, Alexander the Great began his revenge with an invasion of Persia in 334 BC. Despite being greatly outnumbered, Alexander defeated the Persians in three major battles. Finally reaching Parsa in 330 BC, with all Persian opposition having been eliminated, Alexander occupied the city and looted the treasury. Shortly afterwards, Alexander ordered Parsa to be ransacked and then set on fire to avenge the burning of Athens by Xerxes.

Dying in Babylon at the age of 33 in 323 BC, Alexander never got the opportunity to show whether he had any administrative abilities other than being a conqueror. His empire was partitioned, yet much of the territory of the Persians remained intact under the control of one of his generals, Seleucus, and became the Seleucid Empire. In the centuries that followed, despite the rise of other kingdoms, Persepolis was never resettled, and no city was rebuilt over its ruins. Having lost the reason for its existence, Persepolis disappeared from history for over 2000 years.

First Excavations in Persepolis

The fame of Persepolis began to be restored in 1930, when the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago began the first scientific exploration there near the town of Takht-e-Jamshid. Directed by Ernst Herzfeld and Erich Schmidt, excavations and extensive photographic documentation were conducted for eight seasons. They re-discovered the grandeur of the statues, carvings, reliefs, and a number a grand stairways and gateways as they emerged from the dust and dirt that had accumulated on top of the ruins over the centuries. The ash and debris produced by the fire during the destruction of Persepolis had preserved a surprising amount of the art and architecture of the city. Significant archaeological evidence revealed the straight lines of a planned city showing that Persepolis was essentially a city for ceremonial functions.

Locals call the site, Tall-e-Ajori, meaning “brick-made mound”. Constructed 3.5 kilometers outside of Persepolis, this mound measures roughly 80 meters by 60 meters and is believed to be older than Persepolis itself. Excavations here have uncovered an ornamental gateway that is believed to be part of a single building whose purpose is still unknown. Its discovery suggests that it may have stimulated King Darius to build a planned city in the vicinity. It was most likely demolished as part of the destruction of Persepolis by Alexander.

The excavations at Persepolis reveal the orderly rows of streets for a planned city.

With the discovery of terraces and palaces bearing the inscriptions of Darius the Great, this University of Chicago team suggested Darius as the ruler who initiated the construction of Persepolis in 515 BC. As Cyrus died in 530 BC and was buried in Pasargadae, the University of Chicago team found no reason to connect Cyrus to Persepolis.

In 1935, while the excavations were going on, the name of the country was changed from Persia to Iran to reflect that there were more ethnicities in the country other than the Persians/Farsi.

In 1979, this research by the University of Chicago contributed greatly to UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) declaring Persepolis as a registered protected World Heritage Site as the ancient capital of the kings of the Achaemenid dynasty.

What is the Meaning of this Newest Discovery?

These recent findings at Tall-e-Ajori encouraged chief archaeologist Alireza Askari-Charhoudi to state in February 2021 that the building materials, carbon-14 dating, motifs used to decorate the façade of the building, and other evidence, suggests that this gateway was built after 539 BC to honor the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus. He also feels sufficiently confident that Cyrus issued the order for the construction of this gateway which became functional during the reign of his son, Cambyses.

Thousands of glazed bricks measuring 33 cm square and 11 cm thick form the gateway. Many of them are decorated with flowers and various combinations of winged griffins of Elamite and Achaemenid cultures.

Also found in the gateway at Tall-e-Ajori was a depiction of mushussu.

Most famously known as being depicted at the Ishtar Gate in Babylon, the mushussu is the sacred animal of Marduk, the patron god of Babylon. Part of the mythology of the 6th century BC, it is a hybrid creature, a scaly dragon whose hind legs are bird-like with eagle's talons for its feet, while its forelegs are feline. It has the long neck, head, and horns of a dragon, with a serpent’s tongue protruding. Its tail is also that of a serpent.

Iranian archaeologists are encouraged by the clue that Cyrus initiated construction of this sort away from his Achaemenid hometown of Pasargadae.

With the gateway being merely 3.5 kilometers from the main site at Persepolis, and that it was completed before Darius started building there, it just may be that there is a connection of Cyrus to Persepolis after all.

Even in ruins, sunrise at the palace of King Darius still evokes the grandeur of the Persian Empire.

Endnotes

Ancient Origins: Reconstructing the Story of Humanity's Past. 2014. Excavations Uncover Large Ancient Gate in 2500-Year-Old-City of Persepolis in Iran . November 17. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/excavations-uncover-large-ancient-gate-2500-year-persepolis-iran-0133233.

Destination Iran. 2014. Remarkable Discovery of an Achaemenian Gateway Near Persepolis . November 16. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.destinationiran.com/remarkable-discovery-of-an-achaemenian-gateway-near-persepolis.htm.

n.d. Ernst Herzfeld Excavations Unearth the Persepolis Administrative Archives. Accessed March 31, 2021. https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=4105.

Farrokh, Kaveh (Dr.). 2021. Ruins of Gateway Unearthed near Persepolis. February 23. Accessed March 13, 2021. https://www.kavehfarrokh.com/news/ruins-of-gateway-unearthed-near-persepolis/.

Fishman-Duker, Rivkah. 2019. The Cyrus Debate Ironically Confirms the Truth of Jewish History in Jerusalem. November 3. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://jcpa.org/the-cyrus-debate-ironically-confirms-the-truth-of-jewish-history-in-jerusalem/.

Holy Bible, New International Version. 1984. Colorado Springs, CO 80921-3696: International Bible Society.

Iran Front Page. 2021. Gate of Cyrus the Great Discovered Near Persepolis in Southern Iran. February 9. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://ifpnews.com/gate-of-cyrus-the-great-discovered-near-persepolis-in-southern-iran.

Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2015. Israel Post Issues Cyrus Declaration Stamp. April 16. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/IsraelExperience/History/Pages/Israel-Post-issues-Cyrus-Declaration-stamp-16-Apr-2015.aspx.

Jackson, Wayne. n.d. Cyrus the Great in Biblical Prophecy . Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.christiancourier.com/articles/264-cyrus-the-great-in-biblical-prophecy.

Majlesi, Afshin. 2021. Ruins of Majestic Historical Gateway Unearthed Near Persepolis. February 8. Accessed March 12, 2021. https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/457936/Ruins-of-majestic-historical-gateway-unearthed-near-Persepolis.

Oriental Institute of Chicago. n.d. Persepolis and Ancient Iran. Accessed March 31, 2021. https://oi.uchicago.edu/collections/photographic-archives/persepolis/persepolis-terrace-architecture-reliefs-and-finds.

Szczepanski, Kallie. 2019. What is a Satrap? October 28. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-a-satrap-195390.

Tehran Times. 2021. New light shed on Persepolis. March 5. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/458794/New-light-shed-on-Persepolis.

Whiston, William. 1999. The New Complete Works of Josephus. Colorado Springs, CO 49501: Kregel Publications.

Wikipedia. n.d. Persepolis. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persepolis.

Wood, PhD Bryant G. 2010. Ongoing Saga of the Cyrus Cylinder: The Internationally Famous Grande Dame of Ancient Texts. August 18. Accessed March 19, 2021. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/divided-kingdom/2877-the-ongoing-saga-of-the-cyrus-cylinder-the-internationallyfamous-grande-dame-of-ancient-texts?highlight=WyJlZGVzc2EiLCJlZGVzc2EncyJd.