This article was first published in the Fall 2004 issue of Bible and Spade.

This article was first published in the Fall 2004 issue of Bible and Spade.

The Apostle Paul’s visit to Macedonia marked the first time he set foot on European soil (Acts 16:11). However, this was not the first time the gospel was proclaimed in Europe (cf. Acts 2:10). In fact, the “Macedonian call” (Acts 16:9) seems to imply that there were already believers in Macedonia that needed help in evangelizing their province. Macedonia then became a beachhead for Paul and his company to take the gospel further into Europe. As one writer has commented, “Out of Macedonia, Alexander the Great once went to conquer the Eastern world but later from Macedonia the power of the gospel went to conquer the Western world of Paul’s day” (Swift 1984:250).

Philippi was a major city of the Macedonians, and played an important role in the life and ministry of the Apostle Paul. He also had an effective and lasting ministry in the lives of the believers in the Lord Jesus in Philippi.

Historical Overview

The earliest city that occupied the site of Philippi was called Datos. In 360 BC Greeks from the island of Thasos colonized it. They changed the name to Krenides, meaning “with many springs” because of the abundance of springs in the area (Diodorus of Sicily, Library of History 16.3.7; LCL 7:243). It was also famous for the fertile plain that stretched out before it, as well as Mt. Pangaion to the southwest. To the east of Philippi was the Orbelos mountain range.

In the mountains of that area there were gold and silver mines (Strabo Geography 7, fr 34; LCL 3:355). It was these mines that caused friction between the Thracian tribes and the colonists from Thasos. In 356 BC, the colonists invited Philip II, the king of Macedonia, to help defend them from the Thracian tribes. Seeing the strategic importance of this city as well as the gold and silver mines, Philip II was more than happy to assist them. In the process of helping, he took over the city, enlarged and refortified its walls and renamed the city Philippi in his honor.

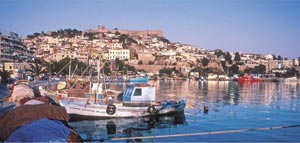

Modern harbor at Kavala (ancient Neapolis) where Paul first landed in Macedonia (Acts 16:11). Macedonia was the northern part of Greece, with Neapolis being its easternmost port. Gordon Franz.

Diodorus of Sicily, a Greek historian of the first century BC, writing in his Library of History, describes what happened next.

And then, turning to the gold mines in its territory, which were very scanty and insignificant, he increased their output so much by his improvements that they could bring him a revenue of more than a thousand talents. And because from these mines he had soon amassed a fortune, with the abundance of money he raised the Macedonian kingdom higher and higher to a greatly superior position, for with the gold which he struck [as coins]...he organized a large force of mercenaries, and by using these coins for bribes induced many Greeks to become betrayers of their native lands (16.8.6, 7; LCL 7:261).

This is a classic example of the world’s Golden Rule: “He who has the gold makes the rules!”

Alexander the Great, the son of Philip II, was able to use the money to raise an army and pay his troops well. They swiftly conquered the Persian Empire, just as the prophet Daniel had predicted (Dn 8:5–8; 11:3–4a).

Ancient road called the Via Egnatia, or Egnatian Way, just above the modern city of Kavala. The Apostle Paul, Timothy and Dr. Luke would have walked on this road from Neapolis to Philippi, about 13 mi (Acts 16:12). Gordon Franz.

Ancient road called the Via Egnatia, or Egnatian Way, just above the modern city of Kavala. The Apostle Paul, Timothy and Dr. Luke would have walked on this road from Neapolis to Philippi, about 13 mi (Acts 16:12). Gordon Franz.

The Romans conquered Macedonia in 168 BC and divided it into four parts. Philippi became the chief city of one of the districts (cf. Acts 16:12). The Romans also built the via Egnatia, a military and commercial road that went across northern Greece, between 146 and 120 BC. The Apostle Paul and his team were able to make effective use of this road for the spread of the gospel in the first century AD.

A pivotal battle in the history of the Roman Empire took place at Philippi. On the Ides of March (March 15, 44 BC) the tyrannical Julius Caesar was assassinated in Rome by a conspiracy led by two Senators, Brutus and Cassius. They misjudged the mood of the people of Rome and had to flee to Asia Minor when the people did not support the assassination. While there, they began to raise an army in order to reconquer Rome and reestablish it as a Republic. Brutus had the audacity to mint coins with his portrait on the obverse and on the reverse two daggers, a liberty cap and the words “EID MAR” (Eidibus Martiis, “on the Ides of March”)! (Molnar 1994:6–10). Mark Antony and Octavian (later to be known as Augustus) led an army from Rome to Philippi in order to confront Brutus and Cassius. The Republican army of Brutus and Cassius had the clear advantage as far as its defensive position, access to supplies, finances and military tactics. However, the tired and ill supplied army of Mark Antony and Octavian defeated them. Upon recognizing their defeat, Brutus and Cassius committed suicide (cf. Acts 16:27). The description of this battle can be read in the writings of the ancient historians Appian (Roman History 4.105-38), Dio Cassius (Roman History 47.35-49; LCL 5.189-217) and Plutarch (Parallel Lives, Brutus 38–53; LCL 6.209-47 and Parallel Lives, Antony 22; LCL 9.183, 185).

This defeat meant that Rome would now have an imperial form of government and not a republican one. It ensured the worship of the deified dead emperor and would later be grounds for contention between the Christians and the Roman government when the Christians would refuse to worship the imperial cult.

After this battle, Philippi was enlarged and became a Roman colony. Discharged soldiers were given fertile land to farm and settled in the city (Strabo, Geography 7, fr. 41; LCL 3.363). Luke was accurate when he said Philippi was a colony (Acts 16:12). After the Battle of Actium in 30 BC more soldiers were settled in Philippi. It should be no surprise that Paul used military terminology when he wrote his epistle to the church of Philippi. Some of the believers might have had relatives that had been in the Roman army. Paul called Epaphroditus “my fellow soldier” (Phil 2:25).

Ancient forum (marketplace) of Philippi, viewed from the acropolis. The forum was completely excavated by the French School at Athens between 1914 and 1938, and Greek archaeologists since 1945. It was a rectangular area 150 ft wide and 300 ft long with porticoes, temples and other public buildings. The bema, or judgment seat, where Paul and Silas were tried, was located at the northern end of the forum (Acts 16:19). Gordon Franz.

Ancient forum (marketplace) of Philippi, viewed from the acropolis. The forum was completely excavated by the French School at Athens between 1914 and 1938, and Greek archaeologists since 1945. It was a rectangular area 150 ft wide and 300 ft long with porticoes, temples and other public buildings. The bema, or judgment seat, where Paul and Silas were tried, was located at the northern end of the forum (Acts 16:19). Gordon Franz.

The Visits of the Apostle Paul

The Apostle Paul visited Philippi for the first time on his second missionary journey in AD 49/50. Following the principle set forth by the Lord Jesus, he went out “two-by-two” with his co-worker Silas (also known as Silvanus) and their disciple Timothy (cf. Mt 10:2–4; Lk 10:1; Acts 15:40; 2 Tm 2:2). Dr. Luke, author of the gospel that bears his name and the book of Acts, escorted them from Alexandria Troas (Acts 16:10–11).

As Paul’s custom was, he sought out the Jewish people whenever he went into a new city (Rom 1:16). His desire for the Jewish people was that they might come to faith in the Lord Jesus as their Messiah (Rom 9:1–5; 10:1–3).

On Shabbat he found a group of women praying by the riverside (Acts 16:13). The phrase “where prayer was customarily made” may indicate there was a synagogue or prayer structure of some sort near the riverside. Recent excavations of the western necropolis of Philippi unearthed a Jewish burial inscription from the second century AD that mentioned a synagogue in Philippi (Koukouli-Chrysantaki 1998:28–35, pl. 11). The Lord opened the heart of Lydia, a God-fearer from Thyatira. She and her household were baptized and she offered Paul and his team hospitality (Acts 16:14–15).

One day, while Paul, Luke and Silas were on their way to prayer, they were harassed by a slave girl possessed with the “spirit of divination” (pythoness). Apollo, the god of prophecy and the giver of oracles at his shrine in Delphi, inspired this “spirit.” Not wanting an endorsement from the “enemy,” Paul cast the demon out of the girl (Acts 16:16–18; cf. Lk 4:31–37).

The owners of the slave girl seized Paul and Silas (but not Luke) and brought them before the magistrates at the forum. They were accused of being Jews and causing trouble in Philippi. This anti-Semitism might have stemmed from the fact that Emperor Claudius had expelled the Jews from Rome the previous year because they were viewed as troublemakers (Acts 18:2; Suetonius, Deified Claudius 25.4; LCL 2.53).

Stone relief found in the harbor of Pireas, the ancient harbor of Athens. It depicts a pythoness, one possessed with a spirit of divination (Acts 16:16), offering a gift to Apollo at his shrine at Delphi. Gordon Franz

Stone relief found in the harbor of Pireas, the ancient harbor of Athens. It depicts a pythoness, one possessed with a spirit of divination (Acts 16:16), offering a gift to Apollo at his shrine at Delphi. Gordon Franz

Paul and Silas were beaten and thrown into prison. While there, they were “praying and singing hymns to God” (Acts 16:25). This joyous attitude while being persecuted has been set forth by James the son of Zebedee (Jas 1:2–4) and Peter(1 Pt 1:5–9; 3:13–4:19).

At midnight an earthquake struck and the Philippian jailer thought all the prisoners escaped. Thinking along the lines of Brutus and Cassius, he decided to commit suicide. Paul stopped him when he informed the jailer that nobody had escaped. The jailer, realizing that there was something different about Paul and Silas, asked them “Sirs, what must I do to be saved?” In unison, they responded, “Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and you will be saved, you and your household” (Acts 16:25–31).

The magistrates decided to let Paul and Silas go. However, Paul, knowing Roman law, asked that the magistrates come and get them out. They wanted an apology because they were Roman citizens who had been falsely arrested. When the magistrates found out Paul and Silas were Romans, they were afraid. I suspect that Paul wanted to hold this over the heads of the magistrates. If they persecuted the church at Philippi or did not protect them, Paul would tell the authorities in Rome what had happened. There would be severe punishment and loss of a job if Rome found out (Acts 16:35–40; cf. 1 Thes 2:2).

Paul knew that Roman citizenship had its privileges! However, he knew that his heavenly citizenship was more important. This citizenship would entitle him to a place in Heaven and a transformation of his earthly body, when the Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ, returned to earth (Phil 3:20–21). This was in marked contrast to the emperors, who were called “saviors,” but could not do anything about immortality and eternal life (cf. 1 Tm 1:17; 6:15–16; Witherington 1994:99–102).

With this, Paul, Silas and Timothy left Philippi on the Via Egnatia for Thessalonica (Acts 17:1). While ministering there, and probably in Corinth, the church at Philippi sent Paul money to help with the work (Phil 4:15–16). Paul thanked them for the gift, and prayed the Lord would bless them for their efforts (Phil 4:17, 19).

Paul visited Macedonia after an extended stay at Ephesus on his third missionary journey. Most likely Philippi was his first stop (Acts 20:1). Then after three months of traveling through Greece, he returned to Philippi and rejoined Luke. They then proceeded to Jerusalem for Pentecost (Acts 20:3–6).

The epistle to the Philippians was written from prison in Rome during Paul’s first imprisonment there (AD 60–62). He thanked the Lord for their fellowship in the gospel and expressed his desire to visit with them again (Phil 1:3–8, 26–27; 2:24). He was also going to send Timothy to visit on his way to minister in Ephesus (Phil 2:19–23; cf. 1 Tm 1:3).

The bema at Philippi, the probable location where the Apostles Paul and Silas were tried before the magistrates (Acts 16:19–24). Bema is the Greek word for a raised speaker’s platform where proclamations were read, speeches made (Acts 12:20–23) and citizens tried before officials (Mt 27:19; Jn 19:13; Acts 25:1–12; Acts 18:12–17). Gordon Franz.

The bema at Philippi, the probable location where the Apostles Paul and Silas were tried before the magistrates (Acts 16:19–24). Bema is the Greek word for a raised speaker’s platform where proclamations were read, speeches made (Acts 12:20–23) and citizens tried before officials (Mt 27:19; Jn 19:13; Acts 25:1–12; Acts 18:12–17). Gordon Franz.

After Paul was released from his first imprisonment (2 Tm 4:16), he went on a fourth missionary journey (Kent 1986:13–15, 21, 47–50). His desire was to go to Spain (Rom 15:28), and church history seems to indicate that Paul visited this country. He also was on the island of Crete (Ti 1:5) and wrote his first epistle to Timothy from Macedonia (1 Tm 1:3; 3:14–15). There is a good possibility that he wrote this epistle from Philippi before he went to Asia Minor.

Was Philippi Dr. Luke’s Hometown?

Some scholars have suggested that Dr. Luke’s hometown was Philippi, which is a possibility borne out by the pronouns used in the book of Acts. Up until chapter 16, Luke is writing about the work of Peter and Paul. When Paul, Silas and Timothy get to Alexandria Troas the pronouns change from “they/them” (Acts 16:7–8) to “us/we” (Acts 16:9–10). Dr. Luke escorts the group to Philippi (Acts 16:11–12). He is with them when they go to the place of prayer (Acts 16:13, 16–17). When Paul and Silas leave Philippi, Dr. Luke stays behind (Acts 17:1). Paul picks him up on his way to Jerusalem at the end of his third missionary journey (Acts 20:5–6). Luke appears to have stayed in Philippi for at least six years.

After Paul cast the demon out of the slave girl, he and Silas were tried before the magistrates and accused of being Jewish, but Luke was not (Acts 16:19–20). Dr. Luke presumably was a respected member of the community, so they did not bring him before the magistrate. But also, Luke was a Gentile (cf. Col 4:11, 14), so the accusation of being Jewish would not have applied.

The answer to this question will never be known for certain unless an archaeologist uncovers an inscription in Philippi with Dr. Luke’s name on it, although this is not outside the realm of possibility. A number of years ago an inscription was found in Corinth with the name of Erastus on it (Rom 16:23; Acts 19:22; 2 Tm 4:20).

The traditional “prison of St. Paul at Philippi.” Most likely this is a cistern from the Byzantine church above it. The apostles Paul and Silas were in prison in Philippi when an earthquake hit, releasing them from their chains (Acts 16:22–26). Charles Dyer.

The traditional “prison of St. Paul at Philippi.” Most likely this is a cistern from the Byzantine church above it. The apostles Paul and Silas were in prison in Philippi when an earthquake hit, releasing them from their chains (Acts 16:22–26). Charles Dyer.

The Book of Philippians

The central theme of the book of Philippians is: “the Philippians’ partnership in the gospel” (cf. Phil 1:5–6; Swift 1984:237; Luter and Lee 1996). This theme is the reason Paul wrote to implore two sisters, Euodia and Syntyche, to be reconciled to one another and have the same mind in the Lord (Phil 4:2–3). Apparently these two sisters were murmuring and disputing and this was hindering the gospel work (Phil 2:14). James, the son of Zebedee, addresses the issue of fighting in the church and states that the root cause of this problem is pride (Jas 4:1–12).

Paul uses an interesting word picture when he describes the women as those who had “labored with me in the gospel” (Phil 4:3 NKJV). This word comes from the gladiatorial arena of two gladiators that fought side by side against the beasts (Hawthorne 1983:180; Witherington 1994:105, 106). In the second and third centuries AD (after the time of Paul), the theater of Philip II was converted into an arena for spectacles between gladiators and beasts (Koukouli-Chrysanthaki and Bakirtzis 1995:23, 24). On a recent visit to Philippi (January 2004) I observed the archaeologists excavating the lions’ den underneath the stage of the theater.

Imagine the gladiators going into the arena to fight the beasts and then turn on each other. The lion would turn to the bear in bewilderment and say, “Aren’t they suppose to be fighting us?” The bear would growl, “Who cares, once they finish each other off, we’ll have them both for lunch!” The apostle Paul would say, “Hey ladies, what’s wrong with this picture? You’re supposed to be fighting the “beasts,” not each other!” (cf. Eph 6:10–17).

Paul brilliantly lays the theological foundation and solution to the problem before he addresses the women. This was the same pattern used by Nathan when he confronted David about his sin with Bathsheba and the murder of her husband, Uriah the Hittite. After Nathan told a parable about a rich man taking a poor man’s lamb, he asked David what should be done. David correctly responded, “The man ought to die.” Nathan pointed to David and said, “You are the man!” (2 Sm 12:1–12).

The fighting was caused by pride. Paul addressed the subject of the mind of Christ that entailed humility in chapter 2. In that chapter, Paul gives four examples of humility; the Lord Jesus Christ (Phil 2:5–15), himself (Phil 2:17–18), Timothy (Phil 2:19–24), and Epaphroditus (Phil 2:25–30). In chapter three, Paul addresses the issue of trusting the flesh.

One can imagine the first time this epistle was read in the church at Philippi. Euodia is sitting on one side of the room listening and thinking to herself, “Amen, preach it Paul, we need to be more humble.” On the other side of the room Syntyche is saying, “That’s right Paul, we should not trust the arm of the flesh.” When chapter 4 was read, Paul in essence said, “Euodia and Syntyche, you need to kiss and make up!” That must have been a tense, yet powerful, moment in the meeting.

There are at least two plausible backgrounds for Paul’s discourse on humility in Philippians 2:1–10, and both might be in view. The first is reflected in a prominent building on the north side of the Via Egnatia on the edge of the forum (marketplace). This building, called a Haroon, was built for the cult of dead king Philip II (Koukouli-Chrysantaki 1998:19). People worshiped him, believing him to be a god (Fredricksmeyer 1979).

Hellenistic theater at Philippi, first built by Philip II in the fourth century BC and later used for gladiatorial combat in the second and third centuries AD. It is estimated that the theater could hold 50,000 people. Charles Dyer.

Hellenistic theater at Philippi, first built by Philip II in the fourth century BC and later used for gladiatorial combat in the second and third centuries AD. It is estimated that the theater could hold 50,000 people. Charles Dyer.

Philip II was, in many ways, like King Uzziah of Judah. Both had material possessions (gold and silver) and a strong military, and because of that, both had hearts that were lifted up with pride (2 Chr 26; Is 2). In the spring of 336 BC, Philip II celebrated the wedding of his daughter Kleopatra to Alexandros, king of Molossia, in the theater at Aigai. Diodorus describes the wedding procession and Philip’s arrogance.

Philip included in the procession statues of the Twelve Gods wrought with great artistry and adorned with a dazzling show of wealth to strike awe in the beholder, and along with these was conducted a 13th statue, suitable for a god, that of Philip himself, so that the king established himself enthroned among the Twelve Gods (Library of History 16.92.5; LCL 8.95).

Moments later he was assassinated by one of his bodyguards. Truly, “pride goes before destruction and the haughty spirit before the fall” (Prv 16:18)! Another example of a king struck down in a theater because he thought he was a god was Herod Agrippa I at Caesarea (Acts 12:20–24; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 19.343-50; LCL 9.377-81).

Diodorus of Sicily goes on to summarize the life of Philip in these terms:

Such was the end of Philip, who had made himself the greatest of the kings in Europe in his time, and because of the extent of his kingdom had made himself a throned companion of the Twelve Gods (Book 16.95.1; LCL 8.101).

The second possible background for this passage are two statues of Julius Caesar and Augustus that stood somewhere in the forum (market place) of Philippi. They have not been discovered archaeologically, but it is known that they existed because of coins minted by Augustus, Claudius and Nero. The bronze coin of Augustus had on the reverse, “three bases: on [the] middle one, [a] statue of Augustus in military dress crowned by [the] statue of Divus Julius wearing toga” (Burnett, Amandry and Ripolles 1992:308, coin 1650). During the reign of Claudius, similar coins were minted, but with his head on the obverse and the two statues on the reverse. Underneath the statue was an inscription in Latin DIVVS AUG (Burnett, Amandry and Ripolles 1992:308; coins 1653 and 1654). This inscription was put up after Augustus had been deified in AD 14. Most likely Paul would have handled his coin while he was in the city. Both Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus were mere mortal men who were deified by the Roman Senate after they died. The Lord Jesus Christ was God manifest in human flesh!

The Heroon, or shrine, of Philip II. The people of Philippi worshipped Philip II as a deity. The Apostle Paul may have had this temple in mind when he wrote about the deity of the Lord Jesus Christ (Phil 2:5–11). Gordon Franz.

The Apostle Paul could have been thinking about the Haroon of Philip II and/or the statue of the deified Caesar in the Forum when he penned the words,

Let this mind be in you which was also in Christ Jesus, who, being in the form of God, did not consider it robbery to be equal with God, but he made Himself of no reputation, taking the form of a servant, and coming in the likeness of men. And being found in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself and became obedient to the point of death, even the death of the cross (Phil 2:5–8 NKJV).

With these verses, he set forth the ultimate example of humility, the death of the Lord Jesus, for the two sisters to follow. Paul went on to say,

Therefore God also has highly exalted Him and given Him the name which is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of those in heaven, and of those on earth, and of those under the earth, and that every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father (2:9–11 NKJV).

With one sentence from Paul’s pen, he has set the Lord Jesus, God manifest in human flesh, apart from every god or goddess in Philippi. That included Philip II, for whom the city was named and the people worshiped. It also included the dead deified emperors, Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus!

Paul had admonished the believers to “esteem others better than themselves” and to “look out for the interests of others” (Phil 2:3–4). A Biblical example from the life of the Lord Jesus that Paul might have had in mind was when the Lord Jesus paid the Temple tax for Himself and Peter. This is a great example of humility and esteeming Peter better than Himself (Mt 17:24–27; Franz 1997:81–87).

In chap. 3 Paul writes about having confidence in the flesh (Phil 3:4). In essence, he is saying,

If anybody could gain God’s righteousness by works, it would be me. I was circumcised on the eighth day, of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of the Hebrews; concerning the law, a Pharisee; concerning zeal, persecuting the church; concerning the righteousness which is in the law, blameless (Phil 3:5–6).

Yet Paul realized all these things were “rubbish” (NKJV) when it comes to gaining God’s righteousness (Phil 3:8–9).

There is absolutely nothing we can do to gain God’s righteousness. If we try to work for our salvation it would be an affront to God. He abhors anything we do to merit salvation because it detracts from the finished work of His Son on the Cross. Paul realized that the only way to gain salvation was to be “found in Christ.” Only He could give us His righteousness whereby we could stand before a Holy God. This righteousness was freely given by grace through faith in the Lord Jesus and not by keeping the Law (3:9).

The Glory in Philippi

Paul describes the Thessalonian believers as “our glory and joy” (1 Thes 2:20). He would have said the same thing of those in Philippi, but he also calls them his “joy, crown and beloved” (Phil 4:1). When we read the account in Acts 16, we see the Lord opening the hearts of Lydia and her household (16:14–15). Also, the demon-possessed girl was delivered from Satan’s hold (16:19). The Philippian jailer and his household believed on the Lord Jesus Christ (16:31, 33).

In his letter to the Philippian church Paul mentions the Praetorian Guards (“palace guards” NKJV, 1:13) who had heard the gospel while Paul was in chains in Rome. This would have been significant for the people at Philippi. Some of the coins of Philippi from the reign of Claudius-Nero were minted with the Latin inscription COHOR PRAE PHIL. This commemorated the “settlement of veterans from the Praetorian cohort at Philippi” (Burnett, Amandry and Ripolles 1992:308; coin 1651). Perhaps some of the believers in Philippi knew Praetorian Guards in Rome and would be interested in Paul’s outreach there. This would help them to pray more effectively for their former colleagues and friends (Phil 1:12).

The Peace of God

Philippi was the scene of a terrible battle in 42 B C and peace in the region was shattered. Later, Emperors Claudius and Nero seemed to have brought a measure of peace to the region. However, neither of them could bring peace to the hearts of men and women.

The Apostle Paul had written to the church at Rome and stated how they could have “peace with God” through faith alone in the Lord Jesus Christ (Rom 5:1). To the church at Philippi he writes about the “peace of God” which will surpass all understanding (Phil 4:7). This peace would come by meditating on the God of Peace and the things that are true, noble, just, pure, lovely, a good report, virtuous and praiseworthy (Phil 4:8–9).

(This article is an expansion of two articles that appeared in Missions, March and April, 2003.)

Bibliography

Burnett, Andrew; Amandry, Michel; and Ripolles, Pere Pau

1992 Roman Provincial Coinage 1. London: The British Museum.

Franz, Gordon

1997 “Does Your Teacher Not Pay the [Temple] Tax?” (Mt 17:24–27). Bible and Spade 10:81–87.

Fredricksmeyer, E. A.

1979 Divine Honors for Philip II. Transaction of the American Philological Association 109:39–61.

Hawthorne, Gerald

1983 Word Biblical Commentary, Philippians. Waco TX: Word.

Kent, Homer

1982 The Pastoral Epistles, rev. ed. Chicago: Moody.

Koukouli-Chrysantaki, Chaido

1998 Colonia Iulia Augusta Philippensis. Pp. 5–35 in Philippi at the Time of Paul and after His Death. eds. Charalambos Bakirtzis and Helmut Koester. Harrisburg PA: Trinity.

Koukouli-Chrysanthaki, Chaido, and Bakirtzis, Charalambos

1995 Philippi. Athens: Archaeological Receipts Funds.

LCL = Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Luter, A. Boyd, and Lee, Michelle

1994 The Ides of March. The Celator 8.11:6–10.

1995 Philippians as Chiasmus: Key to the Structure, Unity and Theme Questions. New Testament Studies 41:89–101.

Swift, Robert

1984 The Theme and Structure of Philippians. Bibliotheca Sacra 141:234–54.

Witherington, Ben, III

1994 Friendship and Finances in Philippi. Valley Forge PA: Trinity.