| This article was first published in the Spring 1999 issue of Bible and Spade. |  |

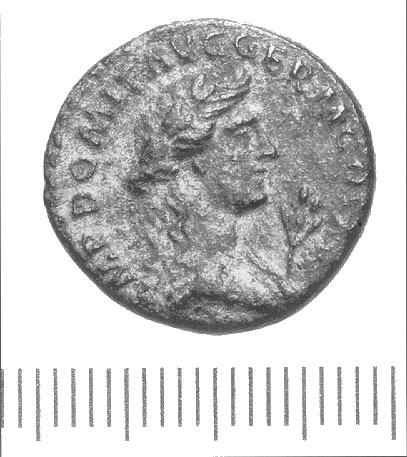

Emperor Domitian, the self-proclaimed “Lord and God” and ruthless dictator, reigned from AD 81 to 96. He was the son of Emperor Vespasian and the brother of Titus, the conquerors of Jerusalem in AD 70. Late in life, Domitian become very superstitious. In fact, on the day before he was murdered, he consulted an astrologer. During this time he also consulted Apollo, the god of music and poetry, as well as light, truth and prophecy! Commemorating his superstition, the emperor minted coins depicting Apollo on one side and a raven, associated with prophecy, on the other (Jones 1989: 266).

The ancients believed a bird’s flight could foretell the future (Kanitz 1973–1974: 47) and Domitian looked to the raven to foretell his immediate future. Ironically, Suetonius, a Roman historian and senator, records, “A few months before he (Domitian) was killed, a raven perched on the Capitalium and cried, ‘All will be well,’ an omen which some interpreted as follows: . . . a raven . . . could not say, ‘It is well,’ only declared ‘It will be well’“ (Rolfe 1992: 385). Emperor Domitian died soon after and all was well!

The Apostle John, exiled to the island of Patmos about AD 95, received a more sure word of prophecy. Not from a raven or Apollo, but from the Lord Jesus Christ Himself. The Book of Revelation begins, “The Revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave Him to show His servants—things which must shortly take place” (Rv 1:1). He goes on to say,“Blessed is he who reads and those who hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those things which are written in it, for the time is near” (Rv 1:3).

|

|

Emperor Domitian minted coins with the head of Apollo, (right) and the raven (left). He consulted Apollo, Roman god of music, poetry, light, truth and prophecy, for knowledge of the future. Depicted as a handsome young man, Apollo was also identified with Helios, the Greek sun-god. Emperor Domitian consulted the raven because its flight pattern was believed to predict the future. Christians have a “more sure word of prophecy.”

The Book of Revelation is a polemic against Emperor Domitian and the Roman world. While Domitian looked to Apollo and the raven to foretell the immediate future, the omniscient Lord Jesus Christ, infinitely greater than Domitian, revealed the future of the world in this book. He instructed John to:

write the things which you have seen [the vision of the glorified Son of Man—Rv 1], and the things which are [the situation of the seven churches in Asia Minor at the end of the first century AD—Rv 2–3], and the things which will take place after this [all the future events recorded in Rv 4–22] (1:9).

This article will examine several aspects of Domitian’s reign and John’s exile to Patmos.

In the 19th century, Bible scholars, linguists, pilgrims, travelers and military intelligence officers from America, England and the Continent began visiting the lands of the Bible. They described sites, recorded manners and customs, drew maps and sketched landscapes. This research began to open up the world of the Bible, making it no longer just a theological treatise, but a Book about real people, events and places. Another dimension these explorers provided students back home was intelligence information for European countries awaiting the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

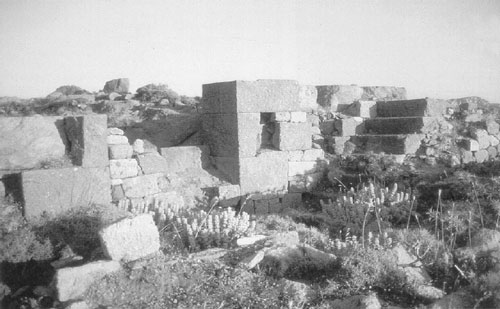

Remains of a gate built by Emperor Domitian at Hierapolis (modern Pamukkale) 6 mi north of Laodicea, Turkey. While he had his name inscribed on the gate when it was constructed, Domitian’s name was removed after his death, by edict of the Roman Senate.

At the turn of the 20th century, Sir William Ramsay explored, excavated and wrote about Asia Minor. Among his important works was Letters to the Seven Churches, about the world of Revelation 2–3. An important recent study on the setting of Revelation 2–3 is Colin Hemer’s Ph.D. dissertation under F.F. Bruce at the University of Manchester in 1969, entitled The Letters to the Seven Churches of Asia in their Local Setting.

I have tried to “follow in the footsteps” of these great explorers. First, by reading the accounts of their travels and, secondly, traveling to the places they visited, making my own observations and taking pictures. From this perspective, we will consider the historical setting of Revelation 1:9 and the Apostle John’s exile to Patmos. I begin with the assumption that Revelation was written in AD 95, during the reign of Emperor Domitian, not in the reign of Nero (Thomas 1994: 185–202).

A dedicatory inscription for the Sabastoi Temple in Ephesus. The name of Emperor Domitian had been chiseled out of the top four lines as a result of the damnatio memoriae issued by the Roman Senate.

The Self-Deified Emperor

Emperor Domitian had a definite ego problem! In Imperial Rome the senate would deify an emperor upon death (Kreitzer 1990: 210–17). However, like Gaius Caligula, and well attested by ancient writers, Domitian could not wait until death and deified himself.

Seutonius (AD 75-ca. 140), in his Lives of the Caesars, wrote: "With no less arrogance he began as follows in issuing a circular letter in the name of his procurators, ‘Our Master and our God bids that this be done’" [Dominus et deus noster hoe fieri iubet] (Rolfe; 1992: 367).

He also delighted in the adulation of the people in the amphitheater when they shouted

“Good Fortune attends our Lord and Mistress” [Domino et dominae feliciter] (Rolfe 1992:367).

In Panegyricus (33.4), Pliny the Younger (ca. AD 61–113) wrote a tribute to Emperor Trajan:

He [Domitian] was a madman, blind to the true meaning of his position, who used the arena for collecting charges of high treason, who felt himself slighted and scorned if we failed to pay homage to his gladiators, taking any criticism of them to himself and seeing insults to his own godhead and divinity; who deemed himself the equal of the gods yet raised his gladiators to his equal.

Dio Cassius, in his Roman History, wrote:

For he even insisted upon being regarded as a god [theos] and took vast pride in being called ‘master’ [despotus] and god [theos]. These titles were used not merely in speech but also in written documents” (Cary 1995: 349).

Elsewhere he wrote:

One Juventius Celsus . . . [conspired] . . . against Domitian . . . When he was on the point of being condemned, he begged that he might speak to the emperor in private, and thereupon did obeisance before him and after repeatedly calling him “master” [despoton] and “god” [theon] (terms that were already being applied to him by others) (Cary 1995: 349).

Later writers repeat the same claim and even embellish it (Jones 1992: 108). However, in Silvae 1.6:83–84, Statius claims Domitian rejected these titles. Other contemporary evidence seems to support the view that Domitian claimed deity. Unfortunately, no inscriptions with such titles on them have been discovered. Dio Cassius again adds an important detail, when he wrote:

After Domitian, the Romans appointed Nerva Coceius emperor. Because of the hatred felt for Domitian, his images, many of which were of silver and many of gold, were melted down: and from this source large amounts of money were obtained. The arches, too, of which a very great number were being erected to this one man, were torn down (Cary 1995: 361).

Upon his death, the Roman Senate was:

overjoyed . . . [assailed] the dead emperor with the most insulting and stinging kind of outcries . . . Finally they passed a decree that his inscriptions should everywhere be erased, and all record of him obliterated (Rolfe 1992: 385).

This decree, the damnatio memoriae, destroyed all the statues and inscriptions of Domitian, such as Domitian’s arch at Hierapolis and dedicatory inscriptions at the Temple of the Sabastoi in Ephesus (Friesen 1993a: 34).

A coin minted by Emperor Domitian in AD 84, depicting Jupiter, chief deity of the Roman pantheon. Also known by his Greek name Zeus, he is holding a thunderbolt (fulmen) in his right hand as a sign of his deity.

A marble portrait of Domitian with an oak-leaf crown, the so-called corona civica, found in Latina, Italy, and now in the National Roman Museum, was probably buried before the emperor died (Sapelli 1998: 24).

What could not be destroyed were coins minted by Domitian because it was impossible to recall all of them. They also provide evidence of Domitian’s boast of deity.

Numismatic Evidence

In an article entitled “The Jesus of the Apocalypse Wears the Emperor’s Clothes,” Dr. Ernest Janzen of the University of Toronto provided two lines of evidence from numismatics for Domitian’s claim to deity. First are coins minted in AD 83, called the DIVI CAESAR (“divine Caesar”) coins. Minted in gold and sliver, they had the bust of Domitia, the wife of Domitian, on the obverse with the inscription DIVI CAESAR MATRI and DIVI CAESARIS MATER, the mother of the divine Caesar! On the reverse was their infant son, born in the second consulship of Domitian in AD 73 and who died in the second year after he became emperor (AD 82) (Rolfe 1992: 345). He is depicted as naked and seated on a zoned globe with his arms outstretched surrounded by seven stars! The inscription surrounding it, DIVUS CAESARIMP DOMITIANIF, means “the divine Caesar, son of the emperor Domitian. “The infant is depicted as baby Jupiter, head of the Roman pantheon of gods, Janzen (1994: 645–647) said:

The globe represents world dominion and power, while stars typically bespoke the divine nature of those accompanied . . . the infant depicted on the globe was the son of (a) god and that the infant was conqueror of the world.

If he was the son of a god, then who was god? Of course, his father, Domitian! I cannot help but use my sanctified imagination and wonder if John did not have this coin in front of him when he penned “and in the midst of the seven lampstands One like the Son of Man, clothed with a garment down to His feet . . . He had in His right hand seven stars” (Rv 1:13, 16). He refers back to this vision in the letter to the church at Thyatira, when the Lord Jesus identifies Himself as the “Son of God” (Rv 2:18).

The second bit of numismatic evidence comes from the coins with the fulmen (“thunderbolt”), the divine attribute of Jupiter, on them, Janzen (1994:648, footnote 55) points out:

In 84 Domitian struck a reverse type Jupiter holding thunderbolt and spear. The first issue of 85 continued this type but the second issue witnessed the fulmen in Domitian’s hand. He and Jupiter would “share” the fulmen for the year 85–6 after which Jupiter remained as a regular type, only without fulmen. From 87–96 Domitian alone held the fulmen, persuasive evidence of a developing megalomania which place [sic] the fulmen in Domitian’s hand and are [sic] clearly patterned after the Jupiter with fulmen type.

One numismatic expert says this type “clearly suggests a parallel between himself and Jupiter tonaus (the thunderer) or the father of the gods” (Mattingly, cited in Janzen 1994: 648, footnote 55).

The dead and deified son of Emperor Domitian sitting on a globe (the earth) with his arms stretched out. Minted between AD 81–84, this is a rare coin because he is grasping for only six stars. Usually the coins have seven stars, like the seven stars in the right hand of the glorified Son of Man (Rv 1:16).

The dead and deified son of Emperor Domitian sitting on a globe (the earth) with his arms stretched out. Minted between AD 81–84, this is a rare coin because he is grasping for only six stars. Usually the coins have seven stars, like the seven stars in the right hand of the glorified Son of Man (Rv 1:16).

Martial, the first century Howard Stern of Rome, confirms this idea in his writings. One of his epigrams, written in AD 94, describing the Gens Flavia (Jones 1992: 1, 199, footnote 1) says:

This piece of ground, that lies open and is being covered with marble and gold, knew our Lord (domini) in infancy . . . Here stood the venerable house that gave the world what Rhodes and pious Crete gave the starry sky [Helios, the sun god, was born on Rhodes according to some traditions; Zeus, the chief Greek god, was born on Crete] . . . But you the Father of the High One did protect, and for you, Caesar, thunderbolt (fulmen) and aegis took the place of spear and buckler (Bailey 1993b: 249).

Sometimes Martial even calls Domitian the “Thunderer” (Bailey 1993b: 157), a title that usually belongs to Jupiter (Zeus) (Bailey 1993b: 311)! Domitian put himself on the same level as Jupiter. Elsewhere in Martial’s writings he calls Domitian “lord” (Bailey 1993b: 75, 231, 249, 257, 261) and “lord and god” (Bailey 1993a: 361; 1993b: 105, 161). Interestingly, after the death of Domitian, Martial repudiates these titles attributed to Domitian (Bailey 1993b: 391). Apparently, he reflected the sentiments of the day while Domitian was alive. Martial may not have believed it, but that is what Domitian wanted and that is what he got.

Another interesting sidelight, is the initials PM on some of Domitian’s coins. Standing for pontifex maximus, it represents the high priest as head of the Roman religion. Biblically, this title belongs to the Lord Jesus (Heb 4:14).

It appears that in AD 85/86 something triggered Domitian to openly claim deity. What it was, I do not know, but the response in Asia Minor was a temple dedicated to the Sabastoi (“emperors”).

A coin minted by Emperor Domitian between AD 92 and 94. The head of Domitian is depicted (left). The reverse (right) shows Domitian standing and holding a thunderbolt in his right hand. Symbol of deity, the thunderbolt (fulmen) is usually associated with Jupiter/Zeus. The Roman goddess Minerva (Athena of the Greeks) stands behind Domitian.

The Sabastoi Temple in Ephesus

In 1930, Austrian archaeologist Josef Keil began to excavate an artificial terrace near the southwest corner of the Upper Agora in Ephesus, Turkey. As excavations progressed, it became clear that this terrace, measuring 85.6 x 64.5 m. supported the foundation of a temple (Friesen 1993b: 66).

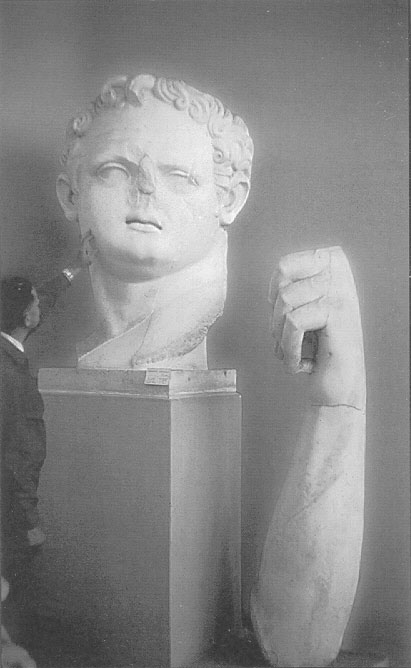

In one of the vaults the “head and left forearm of a colossal akrolithic [wooden statue with extremities made of stone] male statue” was discovered, which lead the excavator to identify it as the Temple of the Sabastoi (Friesen 1993b: 60).

The structure was an octastyle temple of the Ionic order, measuring 34 x 24 m at its base. “The cella had an interior measurement of about 7.5 x 13 m” (Friesen 1993b: 64). East of the temple stood an altar (Friesen 1993b: 67). The north side of the terrace had a three-story facade. The top level had engaged figures of various deities, supporting the terrace above. Originally the facade had 35–40 engaged figures of Eastern and Western gods and goddesses. Today, two figures, Attis and Isis, both Eastern deities, have been restored (Friesen 1993b: 70, 72).

In the last 125 years of research and excavations at Ephesus, 13 inscriptions dedicated to the provincial temple in Ephesus have been discovered. These rectangular marble blocks were placed by various cities of Asia Minor in recognition of Ephesus being the neokoros (“guardian” or “caretaker”) of this temple (Friesen 1993b: 29, 35). In these inscriptions the name Domitian is chiseled out, and in some cases Theos Vespasian is in its place (Friesen 1993b: 37). Removal of Domitian’s name came from the Roman Senate’s edict to erase any mention of Domitian.

Several questions should be asked regarding this temple. First, to whom was the Temple of the Sabastoi dedicated? It probably held a statue of Domitian, possibly his wife Domitia (Friesen 1993b: 35), and probably included the rest of the Flavians: Vespasian, his father, and Titus, his older brother.

The north side of the Sabastoi Temple in Ephesus. The two pillars on the left are the eastern deities Attis and Isis that supported the platform where the statue of Emperor Domitian stood. The structural design of this portion of the temple was symbolic of the gods and goddesses supporting the new deity, Emperor Domitian.

Second, when was the temple fully functional? Friesen (1993b: 44, 48), doing careful detective work with the inscriptions, suggests the date of September AD 90. Most likely it was begun after Domitian expressed the opinion that he was a god (AD 85/86).

Third, whose head did the colossal statue represent? When first discovered in 1930, the excavator identified it as Domitian. Georg Daltrop and Max Wegner later questioned this identification. On the basis of facial features from portraits, they suggest it depicted his older brother Titus. However, other art historians still think it belongs to Domitian (Friesen 1993b: 62). This akrolithic statue, made of a wooden body, now disintegrated, and stone extremities, stood about 25 ft tall (Friesen 1993b: 63, 1993a: 62). The left hand had a groove in it where a spear was placed. This description accords historically with Ephesian coins depicting the Temple of the Sabastoi with a statue in front holding a spear (Friesen 1993b: 63).

Remains of the statue of Emperor Domitian found in the Sabastoi Temple. Made of wood and marble, the statue stood about 25 ft high.

Fourth, where was the statue placed in the temple complex? Some have suggested it was outside in the courtyard. However, the torso was probably wooden and would deteriorate in the inclement weather. Friesen (1993a: 32) notes that the back of the head was not finished, thus “the statue could only have been displayed in front of a wall where visitors were not expected to go behind it.” The most logical place was inside the temple. Most likely, similar statues of the other Flavians were inside (Friesen 1993b: 62).

Fifth, what did the temple complex symbolize? Approaching the Temple of the Sabastoi from the Agora, with its northern facade and engaged deities supporting the temenos, was intentionally symbolic. Friesen (1993b: 75) remarks:

The message was clear: the gods and goddesses of the peoples supported the emperors, and, conversely, the cult of the emperors united the cultic system, and the peoples, of the empire. The emperors were not a threat to the worship of the diverse deities of the empire; rather the emperors joined the ranks of the divine and played their own particular role in that realm.

Ephesus, with its harbor, was the major commercial center of Asia Minor. Pilgrims and traders mixed their commercial ventures with cultic worship of the emperors. I suggest that first century Ephesus was a prototype of the future religious and commercial center predicted in Revelation 17 and 18, called “Mystery Babylon” and controlled by the Antichrist. Interestingly, Farrar (1888: 355), in his monumental The Life and Work of St. Paul, says of Ephesus:

Its markets, glittering with the produce of world’s art, were the Vanity Fair of Asia. They furnished to the exile [of] Patmos the local colouring of those pages of the Apocalypse in which he speaks of “the merchandise of gold, silver” (Rv 18:12, 13).

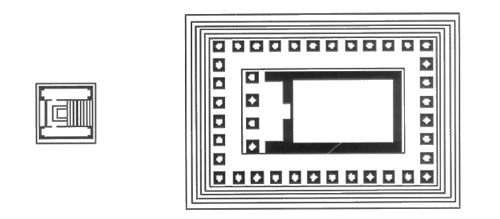

Reconstructed plan of the altar and temple of the Sebastol (Greek for “Emperors”) in Ephesus. It was constructed sometime after AD 85/86, in response to Domitian’s claim of deity.

The first century church could relate to this.

In the midst of all this commercial and cultic activity, believers in the Lord Jesus Christ took a stand for Him (Rv 2:2–3). The Apostle John, one of their elders, refused to participate in emperor worship and preached against it. While on Patmos he received the revelation from the Lord Jesus, a polemic against emperor worship and Domitian in particular. Revelation 1:9 says that John was on Patmos “for the word of God and for the testimony of Jesus Christ.”

The serious Bible student knows there are at least three different interpretations for that verse. First, the Lord sent John to the island specifically to receive the revelation. Second, John voluntarily went to the island to preach the gospel. Third, he was banished by the Roman government because of preaching the gospel (Thomas 1992: 88, 89). The third is most likely the primary interpretation, but the other two are correct as well! John was exiled because he preached the gospel and against emperor worship, but the Lord in His sovereignty used this opportunity to give him the book of Revelation and while he was there, he had opportunities to proclaim the gospel.

Conclusion of the Matter

I wonder if the Apostle John ever saw the statue of Domitian in the Temple of the Sabastoi? If he had, I am sure he refused to bow and worship it, or even burn incense on the altar before it. What a contrast between this lifeless stone statue of a mere mortal and John’s vision of the resurrected and living Savior:

One like the Son of Man, clothed in a garment down to the feet and girded about the chest with a golden band. His head and His hair were white like wool, as white as the snow [Domitian was bald!], and His eyes like a flame of fire, His feet were like fine brass, as if refined in a furnace, and His voice as the sound of many waters; He had in His right hand seven stars [as opposed to a spear in Domitian’s left hand], out of His mouth went a sharp two-edged sword, and His countenance was like the sun shining in its strength (Rv 1:13–16).

When John saw this One, he fell down as dead (Rv 1:17a). He worshipped Someone infinitely greater than the mortal and dead emperors. He worshipped the One who was the “First and the Last,” and the One “Who lives, and was dead and is alive forever more” (Rv 1:17b, 18).

Is it any wonder that John also recorded the statement of the four living creatures, “Holy, holy, holy Lord God (Kurios ho theos) Almighty. Who was and is and is to come” (Rv 4:8)? The contrast of the “Lord Gods” was obvious for any believer living in the first century. Domitian tried to legislate public and private morality, yet he himself was immoral: an adulterer, involved in incest, responsible for the murder of his niece Julia. She died from a botched abortion after Domitian impregnated her. Others were murdered at Domitian’s command, because he felt they were a threat to his rule. He was blasphemous. He abused animals. Sitting in his room he would catch flies and stab them with a “keenly sharpened stylus.”

On the other hand, the Lord Jesus Christ is “holy, holy, holy.” The One who could not sin, would not sin, and did not sin (Jas 1:13, 2 Cor 5:21, Heb 4:15). He was the spotless Lamb of God (1 Pt 1:19). Domitian called himself Dominus Dues Domitianus (D.D.D). Yet the Lord Jesus is the “Lord God Almighty,” El Shaddai!

Domitian was born October 24, AD 51, and murdered September 18, AD 96. He was cremated and his ashes, mingled with those of his niece Julia, were buried in the temple of Gens Flavia on the Quairinal Hill in the sixth Region, built over the house where he was born (Jones 1992: 1; Richardson 1992: 181). Yet, the Eternal Son of God is the One “Who was and is and is to come!” Domitian reigned only 15 years (September 13, AD 81-September 18, AD 96), but King Jesus will reign for a thousand years as “King of Kings and Lord of Lords” (Rv 19:16; 20:4–6). Believers in the Lord Jesus during the first century would have been encouraged (and blessed) by reading the Book of Revelation.

Bibliography

Bailey, D. R. S. (trans.)

1993a Martial’s Epigrams, Vol. 1. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

1993b Martial’s Epigrams, Vol. 2. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

Cary, E. (trans.)

1995 Dio Cassius Roman History, Epitome of Book LXI-LXX. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

Friessen, S.

1993a Ephesus: Key to a Vision in Revelation. Biblical Archaeology Review 19.3: 24–37.

1993b Twice Neokoros, Ephesits, Asia and the Cult of the Flavian Imperial Family. Leiden: E J Brill.

Hemer, C.

1986 The Letters to the Seven Churches of Asia in Their Local Setting. Sheffield: JSOT.

Janzen, E.

1994 The Jesus of the Apocalypse Wears the Emperor’s Clothes, SBL 1994 Seminar Papers. Atlanta: Scholars.

Jones, J.

1989 A Dictionary of Ancient Roman Coins. London: Seaby.

Kanitz, L.

1973–1974 Domitian the Man Revealed by His Coins. Journal for the Study of Ancient Numismatics 5: 45–47.

Kreitzer, L.

1990 Apotheosis of the Roman Emperor. Biblical Archaeologist 53.4: 210–217.

Ramsay, W.

1993 The Letters to the Seven Churches. Peabody MA: Hendrickson.

Rolfe, J. (trans.)

1992 Suetonius, The Lives of the Caesars, Domitian. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

Sapelli, M.

1998 Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme. Milan: Electa.

Thomas, R.

1992 Revelation 1–7. An Exegetical Commentary. Chicago: Moody.

Editorial note- All Scripture quotations in this article are from the New King James Version.