Evaluating the conclusions of Erez Ben-Yosef regarding the Aravah Valley Copper Mines excavations

There is a place at the southernmost point of Israel, almost touching the Gulf of Aqaba. It is full of thousands of abandoned copper mines and smelters that are thousands of years old. It is hot, very hot. Temperatures of 115° are not unusual. It is dry, unbelievably dry. It rains less than one inch per year. Death Valley gets twice that.

It is hard to imagine working here, working at hard manual labor. It is impossible to imagine hundreds or thousands of men working in this sun. Miners were sent here to die. Romans sent condemned Christians to this place.

This is as remote as it can be and still be in Israel. Excavating the copper mines is not what archaeologists dream of – the mines are not the ruins of great walled cities, grand palaces, or pivotal battles of antiquity. But the mines are at the center of a firestorm raging in biblical archaeology. The copper mines are radically reshaping presuppositions about nomadic societies and providing a powerful argument that the biblical accounts of the United Monarchy, the Exodus and the Conquest are true.

The Copper Mines

The copper mines are in the Aravah Valley which runs north from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Dead Sea. The border between Israel and Jordan runs up the middle of the Aravah Valley. There are significant mines and smelters at two locations, Timna, which is at Israel’s southernmost tip, and at Faynan which is 60 miles north but on the Jordanian side of the border.

Credit: Google EarthFig. 1 Regional location map, Faynan, Timna Valley and Umm Bogma

Credit: Google EarthFig. 1 Regional location map, Faynan, Timna Valley and Umm Bogma

More than 10,000 mine shafts have been discovered at Timna and a similar number at Faynan. Some of the shafts are 130-230 feet deep and many develop into complex tunnel systems. Smelting of the raw rock into raw copper at the sites resulted in “dozens of heaps of slag and other industrial waste, some more than six meters high.” (Ben-Yosef 2019c, p. 6)

Credit: WikiCommonsFig. 2 Copper mines, Timna Valley, Negev Israel

Credit: WikiCommonsFig. 2 Copper mines, Timna Valley, Negev Israel

Credit: T.E. Levy, Levantine Archaeology Lab, UC San DiegoFig. 3 Industrial waste ("slag") from Faynan

Credit: T.E. Levy, Levantine Archaeology Lab, UC San DiegoFig. 3 Industrial waste ("slag") from Faynan

At this copper production site in Faynan, Jordan archaeologists dug through 20 feet of slag to get samples that covered over four centuries of mining.

The operations required sophisticated logistics to support. At any given time, the sites would have had hundreds or thousands of workers. Nothing grows nearby and there is no water in the nearby desert, so the workers would have had to be supplied with water and food transported across considerable distances. The smelters required charcoal, clay, flux, ground stones and other materials which also had to be brought in. (Ben-Yosef 2019b, p. 369) The hundreds of donkeys used to transport these materials had to be fed, requiring transport of vast amounts of fodder. (Ben-Yosef and Greener 2018) The planning and implementation of such logistical requirements in the extreme heat and aridity of the desert required significant planning, operation and control. (Ben-Yosef 2016, p. 193)

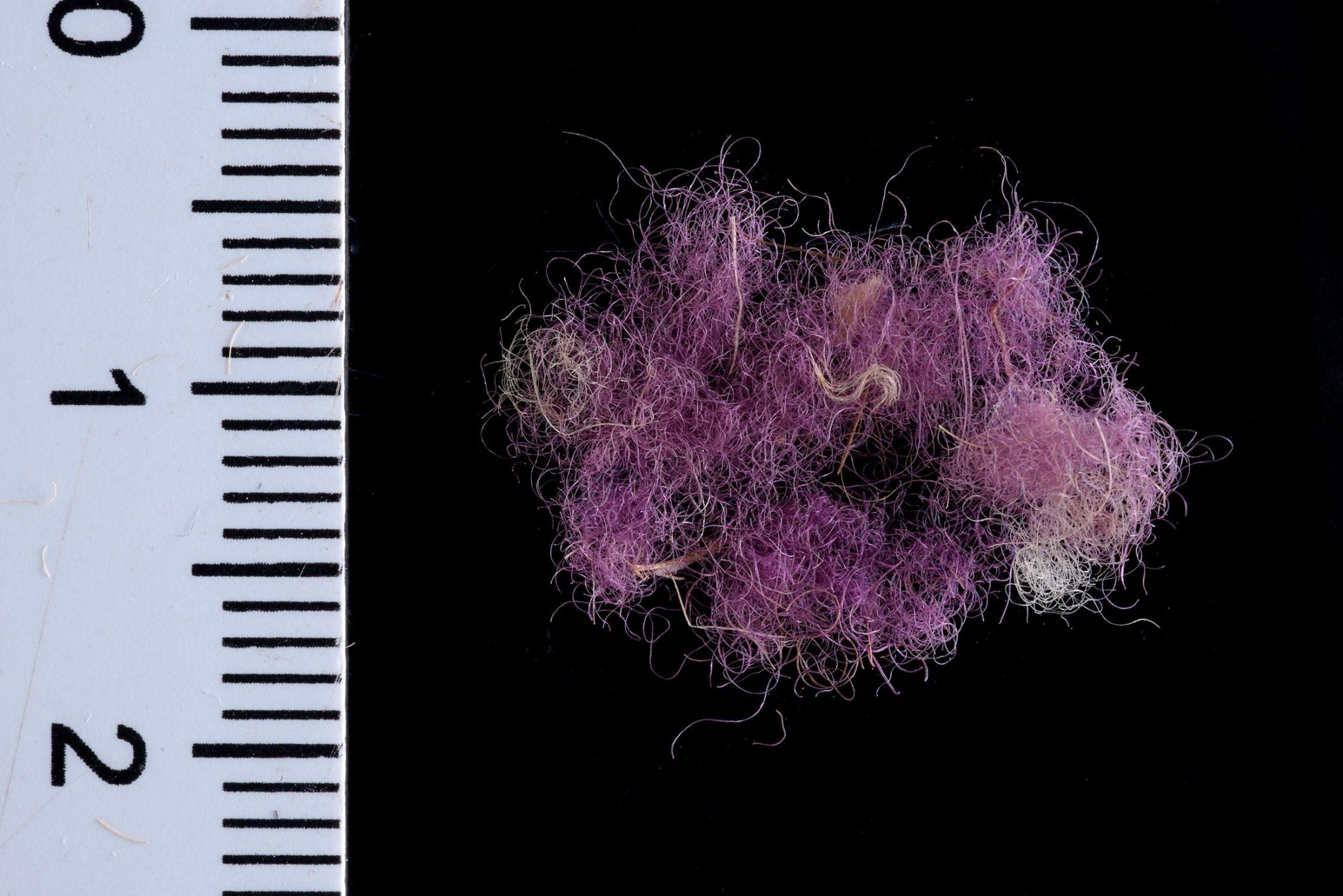

The mines revealed evidence of both lower-echelon workers and elites who operated the smelters and oversaw operations. Evidence of elites includes dyed textiles, especially royal purple (Ben-Yosef 2021a, p. 282; Sukenik et al. 2021), as well as the remains of special food such as the best cuts of meat (Ben-Yosef 2016, p. 180), fish from the Mediterranean (Ben-Yosef 2019b, p. 369), and dates, figs, grapes, pomegranates and olives. (Ben-Yosef and Greener 2018) Some of the food was brought in from as far away as the Mediterranean Sea, about 185 miles away via the ancient roads. (Ben-Yosef and Greener 2018, n. 11)

Credit: Dafna Gazit - Israel Antiquities AuthorityFig. 4 Remnant of "royal purple" fabric found at Timna

Credit: Dafna Gazit - Israel Antiquities AuthorityFig. 4 Remnant of "royal purple" fabric found at Timna

Wool fibers dyed with Royal Purple, ~1000 BCE, Timna Valley, Israel

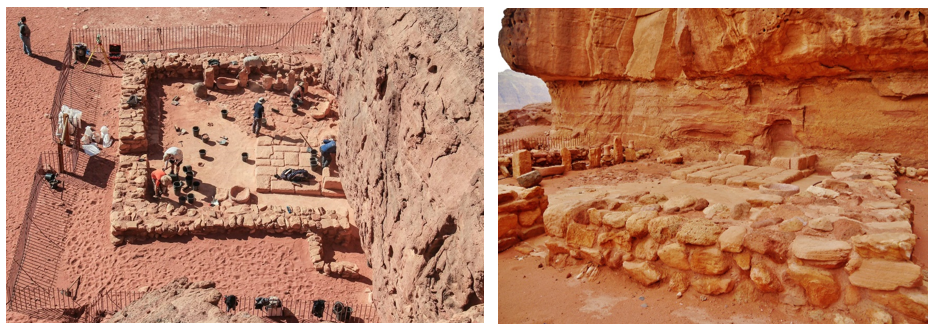

The mining and smelting operations, as well as the trade routes to and from the sites, needed to be protected. A fortress at Faynan (Ben-Yosef 2021b, p. 165), a protective wall around the location of the smelters and elites at Timna (Ben-Yosef and Greener 2018), and remote surveillance posts have been discovered. (Ben-Yosef 2019b, 368n30). Such military activities are additional evidence of a powerful, centrally, and well-organized society.

Fig. 5 Ruins of fortress found at Faynan

Fig. 5 Ruins of fortress found at Faynan

Khirbat en-Nahas Fortress: This is the largest copper mine in the entire Aravah valley. Image shows piles of black copper slag stacked all around the site.

Dating the Mines

In the mid-1930s, Nelson Glueck dated the copper mines at Timna to Iron Age II, that is, from the reign of King Solomon to the end of the monarchy of Judah. The mines quickly became known as “King Solomon’s Mines” because of the popularity of the fictional book by that name, despite the fact that no copper mines are associated with Solomon in the Bible. (Ben-Yosef et al. 2012, p. 32; Ben-Yosef and Greener 2018)

However, in the last half of the 20th century, the archaeological community rejected the Iron Age II dating for both the mines at Timna and at Faynan for two reasons: 1) they assumed that the magnitude of the mining operations required an empire or equivalent political system to manage (Ben-Yosef 2021a, p. 282), and 2) subsequent excavations at Timna by archaeologist Beno Rothenberg seemed to provide a suitable imperial candidate - Egypt. (Ben-Yosef et al. 2012, pp. 32–33) Rothenberg’s excavations revealed a small Egyptian temple (or chapel) with a carved face of Hathor, the Egyptian goddess. (Ben-Yosef 2019c, p. 6)

Relying on that and other finds, Rothenberg redated the vast copper mine fields and the major smelting camps of Timna from the Iron Age to a time 300 years earlier, the period of the Egyptian New Kingdom (13th - first half of the 12th century BC). (Ben-Yosef et al. 2012, pp. 32–33) The idea that any local society rather than a powerful empire could have been responsible for the mines was rejected, more because of archaeologists’ assumptions than any specific evidence. (Ben-Yosef et al. 2012, p. 33) The archaeological community was convinced that no mining had occurred at Timna from the end of the Egyptian New Kingdom until the Roman period. (Singer 1978, p. 21)

The dating for the copper mines further north at Faynan was also revised but in the opposite chronological direction. Having pre-determined that the mining could only be attributable to imperial rule, but with Egypt’s control not extending to Faynan, archaeologists attributed the mining activity at Faynan to the Assyrian Empire of the late 8th and 7th centuries BC (Ben-Yosef 2019c, p. 6)

However, the dating conclusions of the archaeological community were proven wrong. In 2004 a group of archaeologists headed by Thomas Levy began publishing papers describing the results of carbon dating of the mines at Faynan. Contrary to universal expectations, the dates were not in the late 8th and 7th centuries BCE, but rather the 10th and 9th centuries BC (Levy et al. 2008, p. 16465; Levy et al. 2004, p. 877) Those dates demolished the interpretation that Assyria controlled the mines, so much so that Levy characterized Finkelstein and Silberman’s assertion that the mining was carried out under Assyrian auspices as being “pure hyperbole” and “false”. (Levy et al. 2014, p. 981)

In 2009, Erez Ben-Yosef, a young 30-year-old archaeologist, arrived at Timna. His carbon and archaeo-magnetic dating generated similar dates as at Faynan. The majority of the mining and smelting activity at Timna occurred from the 11th century BC to the second half of the 9th century BC, after the Egyptians had left. (Ben-Yosef 2019b, p. 365; Avner 2014, p. 134) In other words, the bulk of the mining and smelting operations at both Faynan and Timna occurred at the same time and were not done by either the Assyrians or the Egyptians. (Ben-Yosef 2019c, p. 6)

Who Did Operate the Mines and Why is it Significant?

If not the Egyptians or Assyrians, then which culture or society did operate the mines? Given the vast scale of the mining and smelting activity, it had to be a culture capable of managing, operating, supplying, and protecting very large-scale projects. Shockingly, both Levy and Ben-Yosef attributed control and operation of the copper mining operations at Faynan and Timna to Edom. (Levy et al. 2008, p. 16465; Levy et al. 2014, p. 992; Ben-Yosef 2019b, p. 363)

Why does the attribution of the Faynan and Timna copper industry to ancient Edom have such profound implications? The answer – because at that time Edom was only a nomadic or semi-nomadic society and archaeologists had made many wrong negative assumptions about the complexity, capabilities, and power of nomadic societies.

Archaeologists are not able to learn much about nomadic societies from the archaeological record. Nomads leave very little trace of their passage and build few if any permanent structures. Nomads typically use vessels of leather and baskets instead of pots and live in tents. Leather vessels and baskets do not survive. Tents need not even leave deep postholes to mark where they once stood. (Ben-Yosef 2021b, p. 156) Ben-Yosef quotes the famous Biblical skeptic, Israel Finkelstein, for the point that nomads are “entirely archaeologically invisible”. (Ben-Yosef 2021b, p. 158), citing (Finkelstein 1992)

So, to understand ancient nomads, archaeologists have looked to a modern nomadic culture, the Bedouins. (Ben-Yosef 2020, p. 36) Based on modern Bedouins, archaeologists have assumed that ancient nomadic cultures were simple, not well organized, lacking in political power, and incapable of creating kingdoms. Archaeologists assumed that nomads had first to settle and develop a sedentary culture in order to achieve social complexity and power. (Ben-Yosef 2021a, p. 283, 2021b, p. 156)

However, archaeologists’ reliance on Bedouins to understand ancient nomads is a mistake. Not all nomadic cultures were necessarily like the Bedouins; some historical nomadic cultures were powerful, centrally organized, complex and capable of creating powerful kingdoms. (Ben-Yosef 2019c, p. 6) Ben-Yosef points to the Mongols as an archaeologically invisible nomadic tribe that was also a kingdom and able to conquer most of the known world. Other powerful ancient nomadic kingdoms included Old Assyria, Old Babylon, Elam and the Nabatean Kingdom. (Ben-Yosef 2019b, p. 374)

Ben-Yosef used the phrase “architectural bias” to describe the requirement imposed by most archaeologists that powerful, centralized cultures must have left stone-built features such as palaces, fortresses, and cities, i.e., architectural features. Archaeologists rely on architectural remains as the “key” in “assessing the strength, size, geopolitical impact and even mere existence of biblical-era kingdoms, and in turn for “solving” questions related to the historicity of the biblical accounts.” (Ben-Yosef 2019b, p. 375)

Ben-Yosef asserts that the overemphasis on stone-built architectural remains has led to some of the most contentious debates in biblical archaeology today, such as whether the Davidic/Solomonic kingdom even existed. (Ben-Yosef 2019a, p. 54) Ben-Yosef correctly points out that the “effect of this bias on biblical archaeology (and consequently on biblical scholarship) cannot be overstated.” (Ben-Yosef 2020, p. 41)

The architectural bias is so strong that it is used to contradict otherwise reliable written historical records from other, nearby cultures. Ninth century BC Assyrian records describe the kingdom of Edom, but that description was ignored because of the lack of contemporaneous Edomite stone-built structures. (Ben-Yosef 2021b, p. 166) But for the accident of the copper mines in the Avarah Valley at Faynan and Timna, we would have had little idea of the existence and substantial power and capabilities of the Edomite kingdom in the 10th-9th centuries BC (Ben-Yosef 2019b, p. 370) Fortunately, however, the Avarah Valley mines provide compelling evidence of a nomadic society that was highly complex and created a strong and hierarchical polity. (Ben-Yosef 2021b, p. 157)

The copper operations have pushed back by three centuries our understanding of the rise of Edom as a powerful state entity (Levy et al. 2008, p. 16465), and have also affirmed the essential historicity of the biblical account of Iron Age Edom in Genesis 36 and 2 Kings 8:21. (Ben-Yosef 2019b, p. 363)

The copper mine operations have implications for not only the historicity of biblical Edom, but also for other disputed historical biblical events such as Israel and its United Monarchy, Israel’s Wilderness Wanderings, and Israel’s confrontation with Edom, Ammon, and Moab. Ben-Yosef condemns the widespread academic skepticism of the historicity of the Israelite entry into Canaan, the era of the Judges and the monarchy as having “no sound grounds.” (Ben-Yosef 2019c, p. 6)

Implications for Israel and the United Monarchy

The evidence found by Ben-Yosef and Levy’s teams at Timna and Faynan has shown that archaeologists have crucially underestimated the size and power of not only Edom but also of Iron Age Israel. (Ben-Yosef 2019b, p. 370, 2021a, p. 282) Due to their architectural bias and wrong assumptions about nomadic populations, modern archaeologists have grossly underestimated the power and size of Iron Age Israel. Finkelstein and Silberman, for instance, estimate that 10th-century BC Judah had only 5,000 people which led to their conclusion that there was no great “United Monarchy”. (Finkelstein and Silberman 2002, p. 143; Ben-Yosef 2021b, p. 171)

However, at that time a substantial part of Israel’s population remained as nomads. In the famous scene where Jeroboam and the representatives of the northern tribes met with Rehoboam and were unsuccessful in their petitions, the text states that “Israel went away to their tents.” (1 Kings 12:16). So, if the population of greater Israel was still largely tent-dwellers, the insistence of archaeologists that a powerful Israelite kingdom must have had numerous fortified cities, stone palaces and fortifications is wrong. As tent dwellers, much of the population of Iron-Age Israel would be archaeologically invisible to archaeologists today.

As confirmation, Ben-Yosef notes that demographic estimates for Iron Age Judah demonstrate that the sharp increase in population in the Eighth century BC cannot be explained solely by natural growth. “[T]he simplest explanation is that substantial components of the population were still nomads, and thus invisible in common archaeological research.” (Ben-Yosef 2021b, 171 n. 15) Levy, the excavator of Faynan, concurs, stating that state formation of Israel likely began several centuries earlier than the Eighth century BC. (Levy et al. 2004, p. 877)

Implications as to the Wilderness Wanderings

Skeptics like Finkelstein have also attempted to use the lack of evidence of the Israelites in the Sinai to dispute the historicity of the Israelites’ post-Exodus Wilderness Wanderings. Finkelstein and Silberman wrote:

Some archaeological traces of their generation-long wandering in the Sinai should be apparent. However . . . not a single campsite or sign of occupation from the time of Ramses II and his immediate predecessors and successors has ever been identified in Sinai. * * * [63] But modern archaeological techniques are quite capable of tracing even the very meager remains of hunter-gatherers and pastoral nomads all over the world. * * * There is simply no such evidence at the supposed time of the Exodus in the thirteenth century BC.

(Finkelstein and Silberman 2002, pp. 62–63)

Finkelstein and Silberman’s conclusions are contradicted by Ben-Yosef’s and Levy’s findings at Timna and Faynan. That is, since wandering tribes are archaeologically invisible, the lack of archaeological evidence of wandering tribes is not evidence of the lack of wandering tribes. Amazingly, Finkelstein and Silberman are contradicted by Finkelstein himself from an earlier article in which he repeatedly stressed the invisibility of desert nomads. (Finkelstein 1992)

Implications as to Israel’s confrontation with Edom, Ammon & Moab

The biblical accounts of Israel’s confrontation during the Exodus with a powerful Edom (Numbers 20:14-21), an Ammonite nation (Numbers 21:24), and a Moabite kingdom (Numbers 22-24) are also disputed by the skeptics. One skeptical archaeologist claims that “There is simply no evidence of Moabite, Ammonite or Edomite kingdoms in MB II or LB I or LB II A” (i.e., the time of the Exodus), and goes on to assert that Biblical literalists are only imagining “invisible kingdoms . . . skulking around pretending to be Canaanite . . . .” (Halpern 1987, p. 59)

The evidence from the Aravah Valley is powerful confirmation that the biblical references to Edom, Moab and Ammon are accurate, as Bryant Wood has previously argued:

God told the Israelites not to attack the Edomites, Moabites and Ammonites since they were related to the Israelites through Esau and Lot, and the land they were occupying was given to them by God and it would not be given to the Israelites (Dt 2:4-5, 9, 18-19, 37; 2 Chr 20:10). Critics are quick to point out that there is no archaeological evidence for the existence of these kingdoms prior to the Iron Age II period (ca. 925-587 BC).

“But, as indicated above, at the time of the conquest these kingdoms were supra-tribal entities which would have left little in the archaeological record.

(Wood 2011)

The Persistent Problem of Non-Evidence

Another problem that is almost ubiquitous among the skeptics in biblical archaeology is the use of non-evidence to “disprove” the Bible. (Merling 2001) As Ben-Yosef has shown, however, any lack of evidence is due not to any problems with the biblical account but rather is due to the limitations of archaeology itself. (Ben-Yosef 2021b, p. 172, 2019c, p. 7)

One obvious example of such misuse of non-evidence in biblical archaeology is the attempt by many skeptics to denigrate the Conquest of Canaan for lack of evidence. Yet many other well-documented invasions, such as the Anglo-Saxon and Norman conquests of England, and the Muslim conquest of North Africa and the Middle East, are similarly plagued with a lack of archaeological evidence. (Isserlin 1983) Yet no archaeologist would dream of challenging their historical reality. Yet as Merling astutely noted, if we applied the standards of biblical archaeology to these other three conquests, we would have to conclude that none actually happened. (Merling 2001, p. 68)

Dibon is another example of non-evidence where conclusions based on the lack of evidence are clearly wrong. Excavations at Dhiban, supposedly the same site as Dibon, show that there was no town there before the ninth century BC. (Krahmalkov 1994, p. 57) Yet the Bible informs us that Dibon existed during the life of Moses and was conquered by the Israelites during the Exodus. Numbers 21:30; 32:3, 34; etc. This supposed conflict between the Bible and archaeology is one of the linchpins of the skeptics’ contention that both the Exodus and Conquest stories are mere fiction. (Krahmalkov 1994, p. 57)

However, we know that the skeptics are wrong. We know that because there is another witness beside the Bible – the records of Egypt itself. Both the records of Thutmose III and of Ramesses II depict and mention Dibon in the 15th century and 13th Centuries BC, respectively. (Bimson and Livingston 1987; Dyer 1983; Krahmalkov 1994) Although we do not know why modern archaeologists cannot find a Late Bronze Age Dibon, we do know that there was such a city just as the Bible says.

As Ben-Yosef courageously opined, the historicity of the Old Testament should be limited to positive evidence only. (Ben-Yosef 2016, p. 195)

But Ben-Yosef does not stop there. He goes on to criticize flaws inherent in the academic field of archaeology. For archaeologists who build their entire academic careers on interpreting rocks and shards, it would not be easy for them to concede that “the lion’s share of historical occurrences is beyond archaeology’s reach . . . .” (Ben-Yosef 2021b, p. 171) Further, it is heady stuff for secular archaeologists to see themselves as the “supreme judge” of the Bible and its historicity. (Ben-Yosef 2019c, p. 6) With comments like those, one must wonder if Ben-Yosef will be invited to many future archaeological conferences!

Summary

The pioneering work of Levy, Ben-Yosef and their teams at Faynan and Timna have conclusively demonstrated that a nomadic society can be large, powerful, and centrally organized yet leave no archaeological trace. The implications for the historicity of the Exodus, Conquest and United Kingdom are obvious: Israel, as a nomadic nation, would have left little archaeological evidence despite its size and power.

Archaeology is a powerful tool but has significant limitations. Its use by biblical skeptics to undermine biblical historicity based on a lack of evidence is a gross misuse of archaeology. As Matti Friedman said in his Smithsonian article on Timna, the primary lesson of the mines is the need for archaeological humility. (Friedman 2021)

Bibliography

Avner, Uzi (2014): Egyptian Timna - Reconsidered. In Juan Manuel Tebes (Ed.): Unearthing the Wilderness. Studies on the History and Archaeology of the Negev and Edom in the Iron Age. Leuven, Paris, Walpole, MA: Peeters (Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Supplement 45), pp. 103–162.

Ben-Yosef, Erez (2016): Back to Solomon’s Era: Results of the First Excavations at “Slaves’ Hill” (Site 34, Timna, Israel). In Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 376, pp. 169–198.

Ben-Yosef, Erez (2019a): Biblical Archaeology’s Architectural Bias. In Biblical Archaeology Review 45 (6), 54-55, 63.

Ben-Yosef, Erez (2019b): The Architectural Bias in Current Biblical Archaeology. In Vetus Testam. 69 (3), pp. 361–387.

Ben-Yosef, Erez (2019c): The Invisible Biblical Kingdom. In Haaretz Weekend, 10/18/2019, pp. 6–7.

Ben-Yosef, Erez (2020): And Yet, a Nomadic Error: A Reply to Israel Finkelstein. In Antiguo Oriente 18, pp. 33–60.

Ben-Yosef, Erez (2021a): Rethinking nomads - Edom in the archaeological record. In David Arnovitz, Sara Daniel (Eds.): The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel: Samuel - The Making of the Monarchy. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, pp. 282–283.

Ben-Yosef, Erez (2021b): Rethinking the Social Complexity of Early Iron Age Nomads. In JJAR 1, pp. 155–179.

Ben-Yosef, Erez; Greener, Aaron (2018): Edom’s Copper Mines in Timna: Their Significance in the 10th Century. Available online at https://www.thetorah.com/article/edoms-copper-mines-in-timna-their-significance-in-the-10th-century, 11/25/2021.

Ben-Yosef, Erez; Ron Shaar; Lisa Tauxe; and Hagai Ron (2012): A New Chronological Framework for Iron Age Copper Production at Timna (Israel). In Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 367, pp. 31–71.

Bimson, John J.; Livingston, David (1987): Redating the Exodus. In Biblical Archaeology Review 13 (5), 40-48, 51-53, 66.

Dyer, Charles H. (1983): The Date of the Exodus Reexamined. In Bibliotheca Sacra 140, pp. 225–243.

Finkelstein, Israel (1992): Invisible Nomads: A Rejoinder. In Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 287 (Aug.), pp. 87–88.

Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002): The Bible Unearthed. Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York, London: Simon and Schuster.

Friedman, Matti (2021): An Archaeological Dig Reignites the Debate Over the Old Testament’s Historical Accuracy. In Smithsonian Magazine, December 2021. Available online at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/archaeological-dig-reignites-debate-old-testament-historical-accuracy-180979011/, 12/2/2021.

Halpern, Baruch (1987): Radical Exodus Redating Fatally Flawed. In Biblical Archaeology Review 13 (6), pp. 56–61.

Isserlin, B. S. J. (1983): The Israelite Conquest of Canaan: A Comparative Review of the Arguments Applicable. In Palestine Exploration Quarterly 115 (2), pp. 85–94.

Krahmalkov, Charles R. (1994): Exodus Itinerary Confirmed by Egyptian Evidence. In Biblical Archaeology Review 20 (5), pp. 54–62.

Levy, Thomas E.; Adams, Russell B.; Najjar, M.; Hauptman, Andreas; Anderson, James D.; Brandl, Baruch et al. (2004): Reassessing the chronology of Biblical Edom. new excavations and 14 C dates from Khirbat en-Nahas (Jordan). In Antiquity 78 (302), pp. 865–879.

Levy, Thomas E.; Higham, Thomas; Bronk Ramsey, Christopher; Smith, Neil G.; Ben-Yosef, Erez; Robinson, Mark et al. (2008): High-Precision Radiocarbon Dating and Historical Biblical Archaeology in Southern Jordan. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 (43), pp. 16460–16465.

Levy, Thomas E.; Najjar, Mohammad; Ben-Yosef, Erez (2014): Conclusion. In Thomas E. Levy, Mohammad Najjar, Erez Ben-Yosef, Neil G. Smith (Eds.): New Insights into the Iron Age Archaeology of Edom, Southern Jordan. Surveys, Excavations and Research from the University of California, San Diego & Department of Antiquities of Jordan, Edom Lowlands Regional Archaeology Project (ELRAP), Vol. 2. Los Angeles: The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, pp. 977–1001.

Merling, David (2001): The Book of Joshua, Part I: Its Evaluation by Non-Evidence. In Andrews University Seminary Studies 39 (39), pp. 61–72.

Singer, Suzanne F. (1978): From These Hills … In Biblical Archaeology Review 4 (2), pp. 16–25.

Sukenik, Naama; Iluz, David; Amar, Zohar; Varvak, Alexander; Shamir, Orit; Ben-Yosef, Erez (2021): Early Evidence of Royal Purple Dyed Textile from Timna Valley (Israel). In PloS one 16 (1), e0245897. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245897.

Wood, Bryant G. (2011): New Light on the ‘Forgotten’ Conquest. Associates for Biblical Research. Available online at https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/conquest-of-canaan/3630-new-light-on-the-forgotten-conquest?highlight=WyJzaGFzdSJd, 9/5/2020.