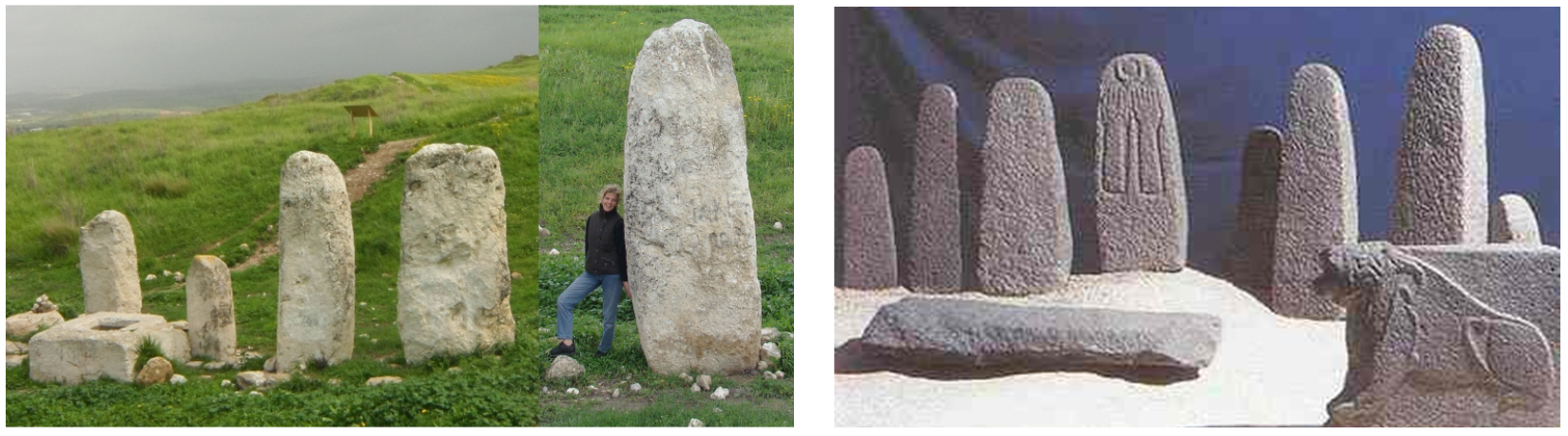

Standing stones are mentioned 34 times in the Bible, sometimes as a positive reference (Exodus 24:4), usually negatively (Deuteronomy 16:22) and, occasionally, in a neutral sense (Genesis 28:18). These standing stones – usually a translation of massebah (Hebrew; plural masseboth) – were always set up by people and have been found in archaeological surveys and excavations across the Holy Land. Unfortunately, none of the specific standing stones mentioned in the Bible have been identified today.

(Photo: Alexander Schick).

RIGHT: At Hazor, Yigael Yadin excavated an impressive collection of Bronze Age standing stones, as well as altars, orthostats and vessels – all carved from basalt. The standing stones pictured were among the cultic accoutrements of one of the city’s Bronze Age temples. (Photo: Mike Luddeni)

Dolmens

Not really considered within the category of “standing stones,” there is a significant number of megalithic standing stones universally referred to as “dolmens” (singular “dolmen”) in English. While there is no indication dolmens are referenced in the Bible, they have been around for millennia and are known across the biblical world.

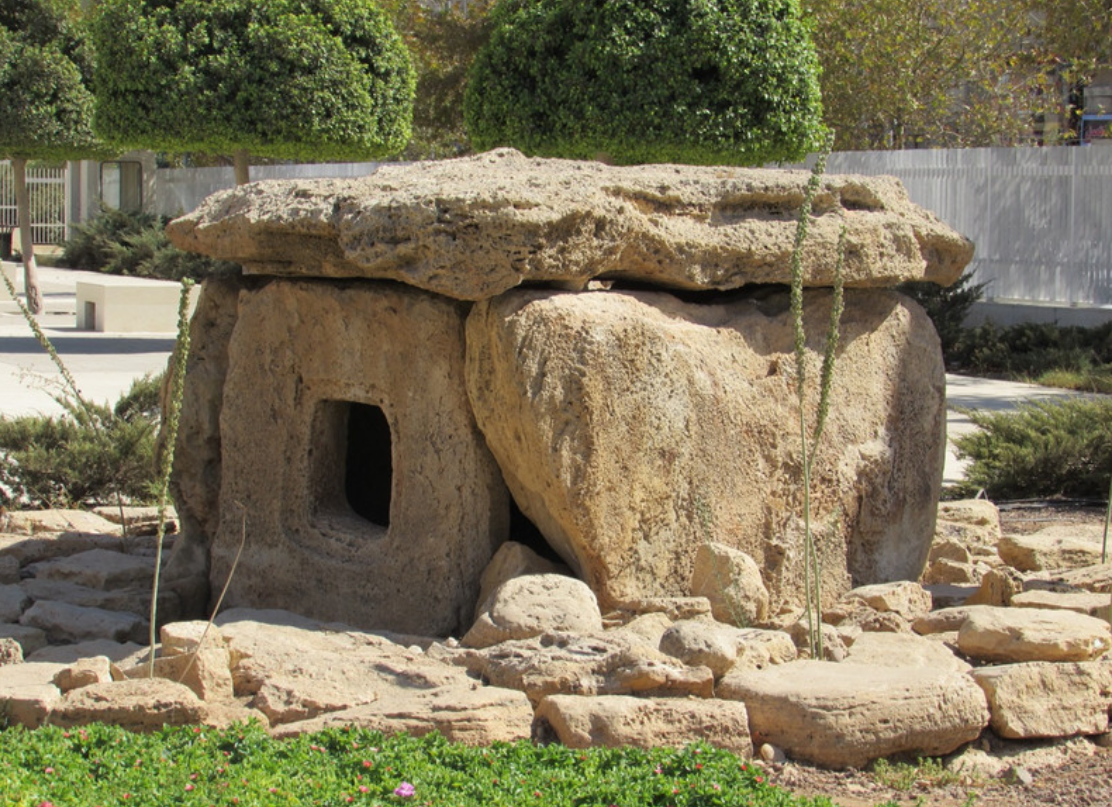

Today, these megalithic (Greek “large/stone) structures are understood to have been used throughout the Bronze Age, beginning as far back as the Chalcolithic – possibly even Neolithic – period. Constructed of multiple megaliths, dolmen stones are generally slab-shaped – some worked but mostly just natural slabs or even boulders. The base of these stones is generally dug into the ground, not just standing on the surface and were “set up” as a unit for some important ancient purposes.

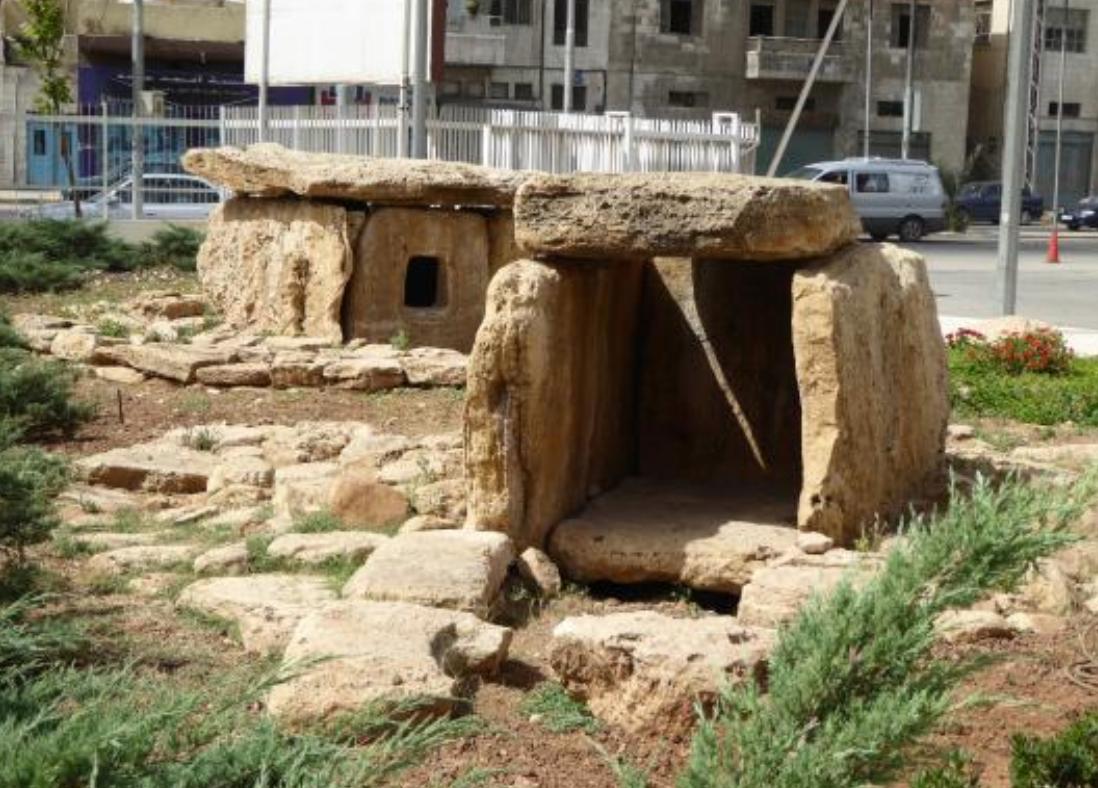

The stereotypical dolmen is comprised of a capstone resting on two or more upright stones, and most dolmens are found in groupings. While the “classic” dolmen is probably a trilithon (Greek; “three stone”) structure with two side stones holding a capstone, what might be considered the “ultimate” dolmen is enclosed on all four sides (the fourth often with some sort of opening ) and a capstone – sometimes also including a stone slab floor (possibly with a chamber beneath the floor).

Dolmens Worldwide

Amazingly, there are an estimated 150,000 dolmens known across Eurasia: extending from Korea (30,000 alone), Japan, China and India; through the Caucasus region of southern Russia and Georgia; into Turkey and through the southern Levant (Syria, Jordan, Israel), north and east Africa (Tunisia and Somalia); as well as north to Malta, Portugal, Spain, France, Britain and western Scandinavia. They are unknown in the western hemisphere. While there are geographical and topographical differences, general form typologies have been created and much has been written on the subject. Yet, there is still not a clear consensus of their precise purpose and function in antiquity.

While the stones of virtually all these ancient monuments are quite large (main stone slabs generally more than a meter high and wide), heavy (main stones starting over 500) and awkward to handle, archaeologists are confident that the application of human and animal muscle in sliding, tumbling, rolling, lifting – in some situations even levers, rollers and ramps – was sufficient to move dolmen components into position. There was no need for giants, aliens or even sophisticated machinery in their construction. Yet, this does not at all diminish their amazing engineering.

Almost as mysterious as dolmens, themselves, is the origin of their name. I suggest the best understanding of the term comes from the Breton language of Brittany, France – part of the Celtic language family and brought to Brittany by migrating Britons during the early Middle Ages. Breton terms for “table” (taol) and “stone” (men) seem to appropriately describe a dolmen and, to no surprise, Brittany has many dolmens – including those believed to be Europe’s oldest.

Due to the lack of opportunity to excavate undisturbed dolmens, datable artifacts associated with their construction and use are seldom available. Consequently, across Eurasia, it is not yet clear when they were constructed and, in many cases, by whom. The best suggestion is that most were constructed around the beginning of the Early Bronze Age but reused through the Bronze Age (even later) in many regions.

Dolmens in the Levant

In the Levant, dolmen fields are concentrated along the Syro-African Rift, as far north as southern Turkey and as far south as Ma’in, Jordan (similar latitude to Bethlehem, Israel). They do not occur in southern Mesopotamia or northern Anatolia. Nor are they found in the southern deserts of Sinai, Arabia, or the Negev – but large dolmen fields are known in Syria, Israel and Jordan.

In the Holy Land, dolmens are most commonly found in locations not best for agriculture – even locations of prominence on extensive plateaus or escarpments where stone is available as well as along wadi slopes for easier downslope transport. While generally found in groupings, they are also often found associated with menhirs (Breton; men “stone” hir “long” or “upright” stone – standing stones) and/or stone circles.

Due to post-use disturbance, dolmens are generally found empty or with minimal and fragmentary artifacts. While human skeletal remains are often identified, they only small scatters of bones often not identifiable as being from the same individual. Thus, the virtual universal scarcity of even semi-complete skeletal remains indicates they did not function as tombs (either for primary or secondary burial).

RIGHT: While there is no evidence of burials in the HMF, ancient family cave tombs have been found in the wadi valleys near Tall el-Hammam. The TeHEP team has yet to find an undisturbed tomb. (Photo: Mike Luddeni)

Dolmens at Tall el-Hammam

Archaeologists have recognized a regular connection between Early Bronze Age settlements and dolmen fields – suggesting an important time and ethnic association. Such is the evidence from Tall el-Hammam (TeH), on the eastern side of the southern Jordan Valley, eight miles north of the Dead Sea – where the author has excavated for 15 years. The first record of this vast dolmen field came from British soldier-surveyor-explorer Claude Conder, with his 1880s survey of the Hammam Megalithic Field (HMF) of dolmens and associated stone configurations (see his 1889 The Survey of Eastern Palestine). The HMF extended several kilometers immediately adjacent both east and south of ancient Tall el-Hammam’s upper and lower cities along the lower hills of the Jordanian plateau – an area not agreeable with field-crop agriculture.

Extensive surveys by the Tall el-Hammam Excavation Project (TeHEP) team in 2009/10 identified and documented nearly 500 dolmens in the HMF. Yet, it is generally believed the area’s original dolmens count was likely over 1,500. Sadly, every year large numbers of dolmens are being destroyed by a combination of residential development, military activity, local commercial sand and gravel operations and vandalism. As of 2020, very few intact dolmens were observed still intact within the HMF.

The TeHEP survey identified three dolmens as being intact. While representing neither the “classic” nor “ultimate” dolmen form – they are among the very few undisturbed-since-antiquity dolmens excavated to-date on either side of the Jordan River.

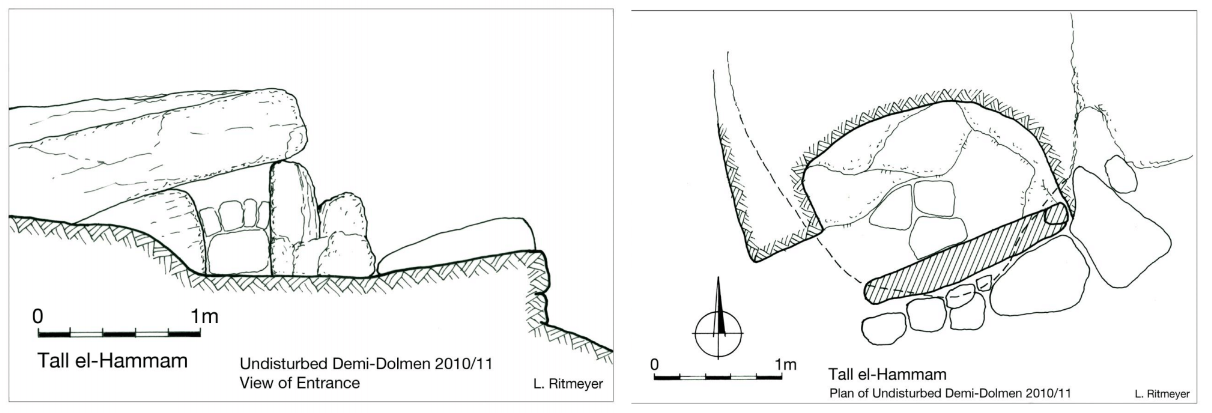

Dolmen B is classified as a demi-dolmen – partially man constructed stone and partially natural rock formation. Its top stone was in its natural position on the ground but was dug out underneath on one end with additional stones erected around it, creating a chamber within. Undisturbed since its last use in antiquity, it was opened by clearing three blocking stones sealed with clay mortar. Within the single chamber, pieces of four vessels representing four different periods were found – Early Bronze II and III, Middle Bronze I, II – indicating this dolmen was re-entered at least three times in antiquity, over a span of almost two millennia. Since excavations on Tall el-Hammam suggested no evidence of population change from the Late Chalcolithic to late in Middle Bronze II, the structure’s serial use likely represents a family ancestral memorial.

RIGHT: Top plan of Dolmen B excavated by the TeHEP team in 2010. Not a tomb, it only contained parts of four vessels from four different periods spanning almost 1,500 years. (Leen Ritmeyer)

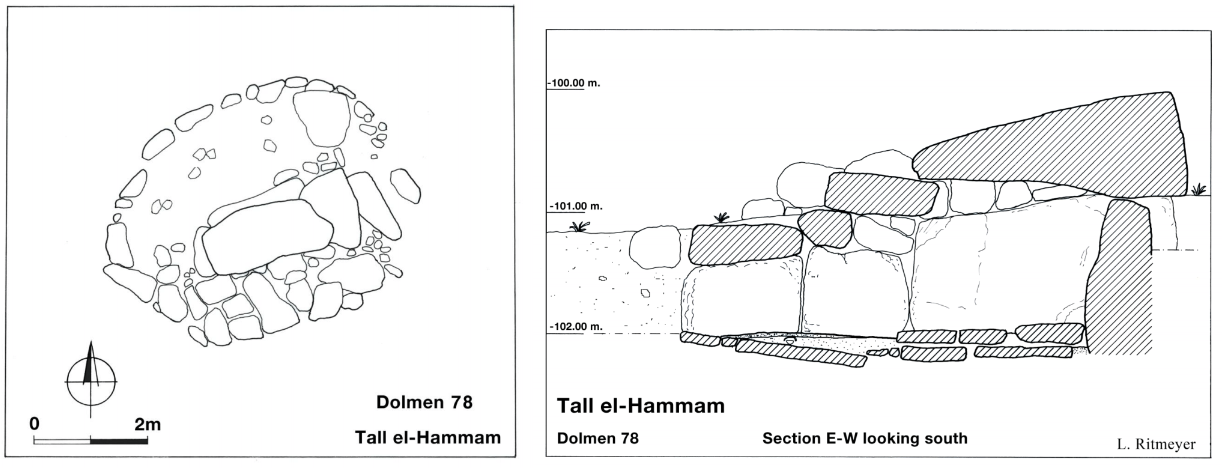

Intact dolmen, Dolmen 78, was found within what seemed to be a discreet field of standing stones – including a central menhir, other stone alignments and a circular platform – all oriented toward Hammam’s sacred district in the center of the lower city. It is suggested this area belonged to an important Hammam family or clan.

RIGHT: Section drawing of Dolmen 78 with view from the north. Note the subterranean chamber numerous ceramic vessels and a small number of bones were found. (Leen Ritmeyer)

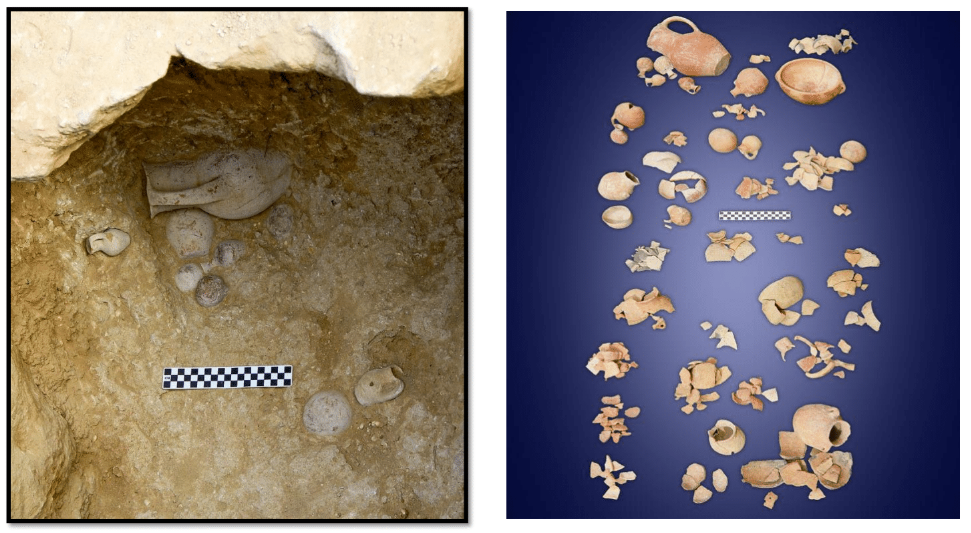

Dolmen 78 had one large capstone slab with three smaller stone slabs on its east end with a stone circle connected to Dolmen 78’s north side. Within, the single chamber (one by two meters) was lined with large stone slabs. The top layer of soil was loose brown fill, likely seeped through the stones over the past 3,000 years. Beneath, was a compact gray fill containing over twenty vessels. These vessels spanned from Late Chalcolithic through Intermediate Bronze Age II. In two locations of the chamber a handful of human bones of bones were found – indicating it was not used for burial.

It is reasonable to consider – if these megalithic stone structures did not serve as tombs, why the great effort, expense and care that went into their construction? At least at Tall el-Hammam, it would seem these structures represented some sort of ongoing memorials, most likely built and maintained by families. The HMF was not a cemetery but used as a sacred memorial “garden” and a place for ritual ongoing gatherings, remembrance of ancestors and even interring of relic objects (ceramic or bone) in honor of those who had passed on.

RIGHT: The vessels in the assemblages as they were found. Located in a distinct part of the Hammam Megalithic Field, it was likely property owned and controlled by a single, well-to-do extended family. (Photos: Mike Luddeni)

Joseph and the Hammam Megalithic Field?

A final thought about the Hammam Megalithic Field. After Jacob died in Genesis 49, “…Joseph directed the physicians in his service to embalm his father. So the physicians embalmed him, taking a full forty days, for that was the time required for embalming” (50:2-3). The Hebrew term “physicians” (probably best understood as “healers”) who were in his service (“his servants”) embalmed (“spiced up” or “prepared for burial”) his father, taking the “full forty day…for embalming.”

Since Jews traditionally buried their dead shortly after death, this action suggests a process somewhat related to mummification – although the term “physicians” suggesting it was not performed by Egyptian priests who carried out the Egyptian mummification ritual. While possibly performed as some sort of concession to the Egyptians, the forty days suggest Jacob’s body was at least buried beneath mummification’s typical pile of natron for the appropriate period – thus preserving Jacob’s body for the long journey to Canaan and his subsequent burial there. Joseph, himself, was also “embalmed” and “placed in a coffin (chest) in Egypt” upon his own death (50:26).

In fulfilling his promise to bury his father in Canaan (49:20-30) and, after receiving Pharaoh’s permission for taking his father’s body to Canaan, a “very large company” (50:9) joined Joseph. Included were “all Pharaoh’s officials – the dignitaries of his court and all the dignitaries of Egypt – besides all the members of Joseph’s household and his brothers and those belonging to his father’s household…chariots and horsemen also went up with him” (50:7-9) to Canaan.

While their destination in Canaan was the cave in the field of Machpelah near Mamre (where Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebecca, Leah and, according to Jewish tradition, Adam and Eve were all buried), it appears Joseph and his very large company traveled the Egyptian military route around the southern end of the Dead Sea and up the east side – along the King’s Highway. Turning west, they passed Mount Nebo and Tall el-Hammam on their way to the Jordan River. Upon arriving at a place called “the threshing floor of Atad” beyond (east of) the Jordan River, they held a solemn ceremony of mourning for Jacob. The local Canaanites were quite impressed and called the place Abel Mizraim (“Mourning of the Egyptians” 50:11).

While the location of the threshing floor of Atad is unknown today, Abel Mizraim might give us a clue. Egyptian hegemony held sway along both sides of the Jordan River in the days of Joseph (while not clearly noted in the Bible, it is known from ancient Near Eastern texts). In fact, the army of 18th and 19th Dynasty Pharaohs came this way on a number of occasions – as recorded in the map lists of Tuthmosis III and Rameses II. Traveling north along the King’s Highway on the Jordanian plateau, their route turned toward the west at the north end of the Dead Sea, passing Iyrre – Dibon Gad – Iktanu – Abel – and arriving at the Jordan River.

When Moses, Joshua and the Israelites also came around the south end and up along the east side of the Dead Sea, they also headed west toward the Jordan with stops at Iye Abarim – Dibon Gad – Almon Diblathaim – the mountains of Abarim, near Nebo – “and camped on the plains of Moab by the Jordan across from Jericho…from Beth Jeshimoth to Abel Shittim” (Num 33:45-49). While Abel Shittim is often translated “Meadow of the Acacia Trees” it is also (and I believe rightly should be) translated “Weeping Acacia Trees” as in Abel Mizraim (“Mourning of the Egyptians”).

Today, most scholars put Abel Shittim at the site of Tall el-Hammam – above the remains of the destroyed and abandoned city-state of Tall el-Hammam. This route from Egypt to Syro-Palestine was well known and likely used by Egyptian traders, government officials and armies passing through the region. The 1,500 dolmens, menhirs and stone circles in the hills north and east of Tall el-Hammam (the Hammam Megalithic Field) probably represented a well-known landmark to all, maybe even significantly so to the Egyptians.

Whether this stop was a specific destination of Joseph’s great company of Egyptians or a spur-of-the-moment choice as an appropriately sacred location for this ritual observance – is it possible Hammam’s still standing dolmen field served as the appropriate venue for the great company of Egyptians mourning Jacob at Abel Mizraim? Furthermore, could Abel Mizraim also be “Abel” of the Egyptian map lists as well as Abel Shittim of the Exodus route – all situated east of the river in the southern Jordan Valley? Could the Hammam Megalithic Field overlooking the ruins of the massive Bronze Age Tall el-Hammam city-state have been a regular stopping point for the Egyptian armies as well as Joseph and Moses on their way to Canaan? It appears to me to be the region’s most likely location for all three historical scenarios.

Bibliography

Collins, S., K. Hamden, G.A. Byers, J. Haroun, H. Aljarrah, et al (2009a) The Tall el-Hammam Excavation Project, Season Activity Report, Season Four: Four: 2009 Excavation, Exploration, and Survey. Filed with the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. 27 February 2009.

Collins, S., K. Hamden, and G. Byers (2009b) Tall al-Hammam Preliminary Report on Four Seasons of Excavation (2006-2009). Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 53: 385-414.

Collins, S., C. Kobs and M. Luddeni (2015) The Tall al-Hammam Excavations. Eisenbrauns.

Schath, K., S. Collins and H. Aljarrah (2011) The Excavation of an Undisturbed Demi-Dolmen and Insights from the Hammam Megalithic Field, 2011. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 55.