Introduction

In the most recent article in The Daniel 9:24–27 Project series (The First Year of Herod the Great's Reign) we looked in detail at when the reign of Herod the Great began. That study examined what two of the main advocates of a 39 BC start for Herod’s reign, W.E. Filmer and Andrew E. Steinmann, had written in defense of their position. After looking at several aspects of their case, we concluded that their approach required ignoring some details, interpreting others inconsistent with a straightforward reading, and proposing errors by Josephus even for events he dated by two mutually-corroborating methods. Particularly troubling was their refusal to regard Antigonus as the full-fledged king of the Jews preceding Herod, viewing him only as a high priest in order to defend their thesis. We concluded that only when we acknowledge that Herod did not truly become king of the Jews until King Antigonus died in the summer of 37 BC are we able to come to valid conclusions about his reign.

With a 37 BC date for the start of Herod’s reign thus set on a firm foundation, we will now look at some events connected with his death. Doing so will help us evaluate the arguments of those who advocate a 1 BC date for Herod’s death, with its ramifications for the dates of Christ’s birth and crucifixion.

The Scriptural Record

Although we would love to be able to use the Scriptures to securely anchor the birth of Christ to a particular year, in God’s wisdom He has chosen to paint a picture with broad stokes only, leaving out many details scholars still endeavor to fill in. But for our purposes we only need to know one thing: Jesus was born sometime during the last few years of the reign of Herod the Great. We can glean that basic information from Matthew 2:1–2, 11–16 (NASB):

Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem, saying, “Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we saw His star in the east and have come to worship Him.”...After coming into the house they saw the Child with Mary His mother; and they fell to the ground and worshiped Him.... And having been warned by God in a dream not to return to Herod, the magi left for their own country by another way. Now when they had gone, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Get up! Take the Child and His mother and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you; for Herod is going to search for the Child to destroy Him.” So Joseph got up and took the Child and His mother while it was still night, and left for Egypt. He remained there until the death of Herod...Then when Herod saw that he had been tricked by the magi, he became very enraged, and sent and slew all the male children who were in Bethlehem and all its vicinity, from two years old and under, according to the time which he had determined from the magi...

Herod the Great in Josephus

With Scripture telling us relatively little about Herod, we turn now to see what Josephus says about the last months of his life. We take up the story at Antiquities 17.6.1 (Whiston translation). As has been done in the past, for brevity’s sake we will include only those details needed for us to follow the timeline.

[An. 4.] Now Herod’s ambassadors made haste to Rome…. But Herod now fell into a distemper; and made his will, and bequeathed his Kingdom to [Antipas] his youngest son: and this out of that hatred to Archelaus and Philip, which the calumnies of Antipater had raised against them…. And as he despaired of recovering…he resented a sedition which some of the lower sort of men excited against him: the occasion of which was as follows (brackets original).

The situation begins with Herod sending messengers to Rome to obtain Caesar Augustus’ permission to put to death his treacherous, parricidal son, Antipater. (For what it’s worth, Whiston places this event in “An. 4,” that is, 4 BC.) The circumstances leading up to this are discussed earlier in Antiquities 16.5, including Antipater’s ill report about his brothers Archelaus and Philip, leading to their being disinherited. The emissaries’ trip coincided with Josephus’ first mention of Herod’s “distemper,” an illness of such severity that it caused him to make out a will and would soon bring about his death. This passage tells us also that he dealt with a “sedition” against him around the same time.

The Implications of Winter

From this passage we may also draw a few inferences not plainly stated. One is that prior to this, Herod’s health was good enough that he came and went as he pleased. Another is that the sending of emissaries to Rome in haste implies that the winter was coming soon, when sea travel on the Mediterranean would shut down. The winter started in early November, when temperatures began dropping and the rainy season came on, and continued into the month of March. Oded Tammuz (“Mare Clausum? Sailing Seasons in the Mediterranean in Early Antiquity,” Mediterranean History Journal 20: 145–162, online at https://www.academia.edu/3843564/Mare_Clausum_Sailing_Seasons_in_the_Mediterranean_in_Early_Antiquity._Mediterranean_History _Journal_20_145-162) gives details about this, quoting the fourth century AD writer Vegetius:

The violence and roughness of the sea do not permit navigation all year round, but some months are very suitable, some are doubtful, and the rest are impossible for fleets by law of nature.… But from the month of November the winter setting of the Vergiliae (Pleiades) interrupts shipping with frequent storms. So from three days before the Ides of November (i.e. 11th November) until six days before the Ides of March (i.e. 10th March) the seas are closed (emphasis added).

Thus, the shipping season ran roughly from April through October, as the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia puts it (cf. https://www.bible-history.com/isbe/S/SHIPS+AND+BOATS/). Various websites dealing with climate provide details about temperature and rainfall typical of winter weather, such as http://www.levoyageur.net/weather-city-JERUSALEM.html and http://nabataea.net/birthdate.html; they show rainfall increasing and average temperatures dropping beginning in November, at which time Herod would likely move to winter quarters at Jericho. The resumption of sea travel in early March indicates that winter’s edge would also have begun tapering off in Jerusalem by this time, but there would have been no hurry to leave Jericho until the heat began to increase there to less comfortable levels.

The pertinence of this data to our study is that it provides background for evaluating certain details Josephus tells us, helping us fit them into a climate-sensitive timeline. For example, the mention that Herod’s ambassadors “made haste” to Rome hints at the imminent onset of winter and the closure of sea travel, so we may suppose their trip took place in late October, 5 BC. That a reply did not get back to Herod until early spring the following year also fits this timetable. Similarly, as discussed below, it helps us place the golden eagle affair in early March. We also note that because the Magi met with Herod at Jerusalem, when we account for travel time from their homeland (likely Persia, where Daniel's influence was strong), it indicates their visit probably took place in the spring of 6 or 5 BC. We don’t really know, and this is not the place to investigate that fascinating question, but it brings some ideas to mind…

The Golden Eagle Affair

We resume Josephus’ tale in Antiquities 17.6.2–4:

There was one Judas, the son of Saripheus; and Matthias, the son of Margalothus…when they found that the King’s distemper was incurable, excited the young men that they would pull down all those works which the King had erected…. For the King had erected over the great gate of the temple a large golden eagle, of great value.… So these wise men persuaded [their scholars] to pull down the golden eagle...”

And a report being come to them, that the King was dead…in the very middle of the day they got upon the place; they pulled down the eagle, and cut it into pieces with axes: while a great number of the people were in the temple. And now the King’s captain, upon hearing what the undertaking was…came up thither; having a great band of soldiers with him, such as was sufficient to put a stop to the multitude of those who pulled down what was dedicated to God. So he fell upon them unexpectedly...he caught no fewer than forty of the young men…together with the authors of this bold attempt, Judas and Matthias (ben Margalothus)…and led them to the King…. And when the King had ordered them to be bound, he sent them to Jericho, and called together the principal men among the Jews. And when they were come, he made them assemble in the theatre: and because he could not himself stand, he lay upon a couch...

Herod…deprived Matthias (ben Theophilus) of the High Priesthood, as in part an occasion (to blame) of this action (the destruction of the golden eagle); and made Joazar, who was Matthias’s wife’s brother, High Priest in his stead…and (on the same day) burnt the other Matthias (ben Margalothus), who had raised the sedition, with his companions (the young scholars), alive. And that very night (of the day the trials took place at Jericho) there was an eclipse of the moon (brackets original, parentheses added).

Those familiar with Antiquities will immediately notice we have left out a significant portion of 17.6.4 dealing with the high priest Matthias ben Theophilus. This is because that material functions as little more than an interesting aside from the main thrust of the passage, namely, the trial at Jericho concerning the golden eagle’s destruction. For some reason holding him partly to blame for the golden eagle affair, Herod removed the high priest Matthias from office and replaced him with Joazar (in 4 BC—note that year—according to the Jewish Encyclopedia, online at http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/10488-matthias-ben-theophilus). Josephus also throws in details about a one-day interruption of Matthias’ high-priestly service by a relative, Joseph ben Ellemus, mentioning that it took place on a fast day, which is understood by most scholars to have been a Day of Atonement due to its discussion in the Talmud in that context. However, the Ellemus episode has nothing to do with the golden eagle affair, so we should not get sidetracked by it. We need focus only on the golden eagle trial. It took place on a single day at Jericho, many people were burned alive for their involvement, and that night there was a lunar eclipse. Further, since Herod is described as clearly manifesting his last illness—he was too weak to stand upright, and there was even a spurious report that he had died (Ant. 17.16.3)—it is clear this trial took place not long before his death.

That the offenders were promptly taken to Herod and then “sent” to the winter quarters at Jericho indicates one of two things: either winter had not yet arrived and Herod planned to incarcerate them there for a while for a later trial in the winter, or it was already late winter (early March) and Herod was just temporarily in Jerusalem during an interval of decent weather, with plans to return to Jericho shortly. The latter seems to make the best sense, because Herod took the seditionists’ destruction of the eagle as a personal insult, and would not have delayed venting his wrath on them as a delayed trial would require.

From these details we can make the following reconstruction. The high priest Matthias’ missed day of Yom Kippur service was probably October 11, 5 BC. Though his act of appointing a relative to take his place that day was a violation of protocol (explaining why the episode was alluded to in the Talmud, in Tosefta Yoma i.4, Yoma 12b, and Yer. Yoma 38d), it was not the sort of personal affront that would have goaded Herod into quick action, so nothing probably came of it, at least immediately. At some point later, in early March of 4 BC, the golden eagle affair took place, with the accused sent to Jericho to stand trial and the high priest Matthias included in the adjudications.

We note in passing that Ernest L. Martin’s recounting of this affair has misrepresented an important detail (http://askelm.com/star/star011.htm):

The rabbis and the young men who assisted them were finally convicted of high criminal actions (sacrilege and sedition). While most of the young men were given milder sentences, the two rabbis were ordered to be burnt alive (emphasis added).

There is no indication in either Wars or Antiquities that Herod gave any of the rabbinical students who pulled down the golden eagle “milder sentences.” Martin implies that only the two rabbis who stirred up the students were burned alive. What Josephus’ record actually says is that Herod “ordered those that had let themselves down, together with their rabbins, to be burnt alive, but delivered the rest that were caught to the proper officers, to be put to death by them” (Wars 1.33.4). Thus, all who were caught in the act of destroying the golden eagle were put to death, though possibly death specifically by burning was restricted to the worst offenders, the two rabbis and the ringleaders who were lowered on ropes. In all events, Antiquities 17.6.4, the later account rightly regarded as the more accurate of the two, says that the ringleader Matthias ben Margalothus was burned alive “with his companions,” which implies that most of the 40-some bold young men who were caught in the act were slain by fire. So the meting out of capital punishments surely took several hours, what with setting up for the burning, likely burning just a few at a time, and continuing until all the condemned had been put to death. The mourning of the bereaved families of the youths would certainly have continued for hours afterward.

When Was the Lunar Eclipse?

So, when was the lunar eclipse Antiquities mentions took place the night of the trial? The only eclipses we need consider are those within 34 years of the death of Antigonus in the summer of 37 BC: “having reigned since he had procured Antigonus to be slain thirty four years” (Ant. 17.8.1). Since we showed in the past that Josephus repeatedly said in Antiquities (1.3.3, 3.10.5, 11.4.8) that Nisan was the first month of the year for him, the 34th year (inclusively reckoned) would have begun on Nisan 1, 4 BC—March 29th. Therefore, we are only interested in lunar eclipses which took place prior to March 29, 4 BC. We have one in the partial eclipse that took place shortly after midnight on March 13, 4 BC. Other eclipses in close proximity to that were total eclipses on March 23 and September 15 of 5 BC; the total eclipse on January 9, 1 BC that Filmer, Steinmann, Finegan and Martin promote fails to meet the time constraints.

Although its advocates are enthralled by the idea that the eclipse in question was the spectacular total lunar eclipse of 1 BC, their perspective is colored by their desire to have the Crucifixion take place in AD 33, plus their idea that a total eclipse would have been more memorable as a harbinger of doom for those who lost their lives to the flames that night. But viewing an eclipse this way reflects a pagan’s superstitious perspective, not that of believing Jews. The Jew was inculcated from youth with the understanding that the Moon was “for signs and for seasons and for days and years,” a time-keeper placed in the heavens by the Living God, not an object of superstitious awe. Therefore, since this is the only lunar eclipse mentioned in Josephus’ writings, it is a mistake to view it through pagan eyes as an omen, one of supposedly heightened import due to being total. Rather, as seen in Josephus’ penchant for double-dating things to securely anchor them on a timeline, the mention of a lunar eclipse should be viewed as having the same function—to objectively date an event.

That being the case, it does not matter whether the eclipse was partial or full, only that it happened at the right time. If we build on all the facts this study has covered so far, we must say that a 1 BC eclipse is three years too late to reconcile with the straightforward sense of Antiquities. By the same token, the two eclipses of 5 BC are too early to fit into the total picture Josephus paints. His mention of Matthias the high priest’s missed Day of Atonement service only makes sense in its context if it occurred during the last few months of Herod’s life, not a whole year earlier; hence, the eclipse in question must have taken place soon after the Day of Atonement on October 11, 5 BC. Thus, of the options we have discussed, the only eclipse that qualifies is that of March 13, 4 BC.

The objection raised by some against the March 13, 4 BC eclipse that it was “only” partial appears to be grounded in the perception that eclipses were viewed by the Jews as harbingers of doom. But if that were true, why is there no mention of other lunar eclipses in Josephus apart from Antiquities 17.6.4, such as both total eclipses of 5 BC? Surely if the Jews had the fundamentally superstitious view of eclipses that characterized the ancient pagans, there were many opportunities in the long history of Jewish misfortunes to have tied various woes to lunar portents. It appears far more likely that the Jewish mindset saw the Moon as Genesis 1:14 describes it, “for signs and for seasons and for days and years,” rather than as an omen imbued with occult significance. The ancient Jew was quite aware from their revered Scriptures that the source of the numerous misfortunes of their history was a result of departing from the ways of their God. We need not impose on the Jewish mind an essentially pagan perspective.

Yet another complaint against the 4 BC eclipse is that it did not take place until after midnight, when supposedly there would have been very few observers to note it. However, we must keep the full situation in view. Since the perpetrators of the golden eagle affair—the young scholars and their esteemed leaders, Judas and Matthias ben Margalothus—were burned alive that night, it is quite reasonable to assume it was a LONG night! We need not imagine that a single huge fire capable of quickly handling 40+ people at once was built, but multiple smaller ones, and not necessarily all at the same time. Given that it would take some time to set things up after the trial ended, it is no stretch of the imagination to suppose that on this particular night, the fact that the penumbral shadow did not begin shading the moon until just after midnight (see https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/JLEX/JLEX-AS.html), and the partial eclipse did not really get underway until around 1:30 am in the morning, should not be viewed as a conclusive strike against this date. Besides, there would have been many onlookers, including the leading men of the Jews that Herod had summoned to Jericho, the families of the young men condemned to death, and those with a deep respect for the two revered rabbis. The night would have been a very long, sleepless one for the bereaved families commiserating together for hours afterwards, probably none of whom would have attempted to return to Jerusalem that night, but would have waited until daylight to depart, perhaps camping out under the stars in the hippodrome. All of these considerations would tend to keep the crowd outdoors and wide awake into the wee hours of the morning, when the lunar eclipse was at its height. Thus, notwithstanding its late hour, the circumstances of this particular eclipse meant it did not lack for eyewitnesses.

A Proposed Timeline of Herod’s Final Days

Ernest L. Martin objects to a 4 BC date for Herod’s passing largely on the basis that there was not enough time for all the events between the eclipse and the Passover festival following Herod’s death (Ant. 17.9.3) to take place (http://askelm.com/star/star010.htm). However, his apparent bias in favor of a 1 BC death date leads him to greatly pad his proposed timeline. He makes some assumptions that have little basis in reality, particularly the claim that Herod’s funeral procession moved at a snail’s pace from Jericho to his burial place at Herodium, advancing just a Roman mile a day for 25 days. In his article “‘And They Went Eight Stades toward Herodeion’” (Chronos, Kairos, Christos: Nativity and Chronological Studies Presented to Jack Finegan, pp. 96–99), Douglas Johnson persuasively argues that Whiston’s suggestion developed by Martin, that the funeral procession of Herod only advanced eight stades (about one mile) per day, was quite flawed. As Johnson makes clear, only a little reflection on its logistical impossibilities indicates it must refer to an initial public funeral procession out of Jericho of eight stades, followed by the rest of the distance to Herodium covered at the speed of a military march. The entire journey could thus have been completed in a single day.

In short, the difficulty Martin sees is related to a false concept of how much time was required for Herod’s funeral. Ed Rickard discusses this issue in some depth at https://www.themoorings.org/Jesus/birth/lunar_eclipse.html, noting:

Douglas Johnson has demonstrated that Ernest L. Martin, for one, has greatly exaggerated the compression. Martin imagines that Herod’s funeral procession took 25 days to carry his body from Jericho to Herodeion, a distance of 23 miles. Yet, as Johnson shows, the body must have been transported to its burial place within a single day. Martin admits that apart from Herod’s funeral, the remaining events could have occurred within 33 days. If 33, why not 30? It is impossible from our perspective to set dogmatic lower limits. We conclude that Josephus’s account of these events does not forbid placement of Herod’s death after the lunar eclipse in 4 BC.

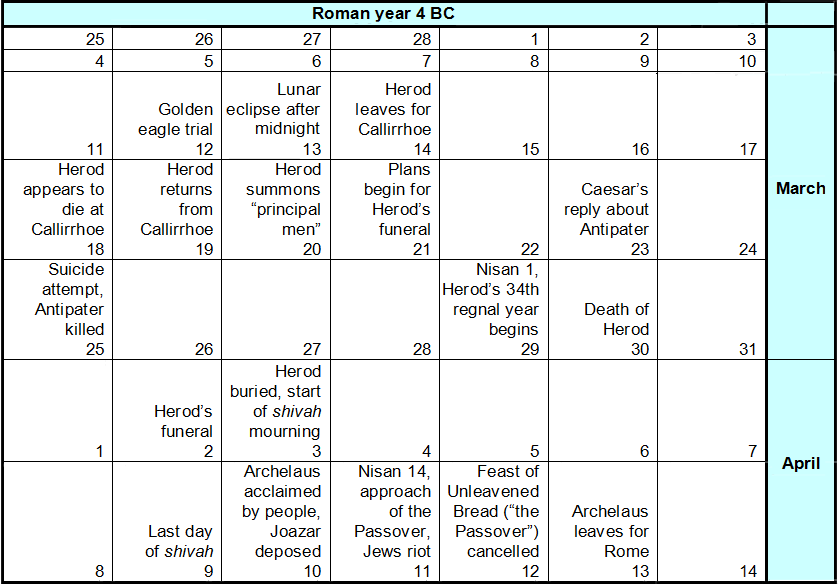

This is a good observation, but I would like to take it further, from generalities to specifics. If the eclipse of March 13, 4 BC is the correct one, we should be able to construct a reasonable timeline that allows for everything Josephus mentions between the eclipse and funeral to take place. Let us see if this is the case, beginning with Antiquities 17.6.5. We will use the calendar given at http://www.cgsf.org/dbeattie/calendar/?roman=-3, although, being a calculated calendar, it is possible the date proposed for the Passover is off a day or two (since it is the visible moon that actually determined the dates of the festivals in the biblical period). Since the Sabbath forbade work or significant travel (a “Sabbath day’s journey,” about 2/3 of a mile, Acts 1:12, was acceptable), any realistic timeline should also not require significant trips from Friday evening through Sunday morning, so we will work around Sabbath days in the following proposal.

But now Herod’s distemper greatly increased upon him, after a severe manner…when he sat upright, he had a difficulty of breathing…also convulsions in all parts of his body.… Yet was he still in hopes of recovering…and went beyond the river Jordan, and bathed himself in the warm baths that were at Callirrhoe…. And when the physicians once thought fit to have him bathed in a vessel full of oil, it was supposed that he was just dying. But upon the lamentable cries of his domesticks, he revived: and having no longer the least hopes of recovering, he…came again to Jericho.

The corresponding passage in Wars 1.33.5 makes better sense:

After this, the distemper seized upon his whole body, and greatly disordered all its parts with various symptoms…Besides which he had a difficulty of breathing…and had a convulsion of all his members…. Yet…hoped for recovery…. Accordingly, he went over Jordan, and made use of those hot baths at Callirrhoe…. And here the physicians thought proper to bathe his whole body in warm oil, by letting it down into a large vessel full of oil; whereupon his eyes failed him, and he came and went as if he was dying; and as a tumult was then made by his servants, at their voice he revived again…. Yet did he after this despair of recovery…. He then returned back and came to Jericho…

The matter of the golden eagle affair having ended, let us suppose that the morning following the lunar eclipse, still Tuesday, March 13, without the trial to distract him from his health woes, Herod’s attention turned inward and focused fully on his pains. Meeting with his doctors that day and getting their treatment recommendation, we may suppose that he made his plans and the day after the lunar eclipse, Wednesday, March 14, he departed early for Callirrhoe. This was less than 20 miles from Jericho (and accessible by boat—see the harbor at https://www.bibleplaces.com/callirhoe/), so we may assume he arrived there by that evening.

Let us now suppose he spent the next three days, March 15–17 (including the Sabbath), trying the hot springs treatment, but with no apparent benefit. This led his doctors to try something different, resulting in the scary experience in the oil bath on the fourth day, Sunday, March 18. That experience convinced Herod that this course of action was not working (he had “no longer the least hopes of recovering”), so he cut short further treatments there and departed for Jericho, getting back no later than the evening of Monday, March 19. Continuing through to the end of Antiquities 17.8.1:

He commanded that all the principal men of the intire Jewish nation, wheresoever they lived, should be called to him.… And when they were come, he ordered them to be all shut up in the hippodrome: and sent for his sister Salome, and her husband Alexas, and spake thus to them: “I shall die in a little time, so great are my pains.... He desired therefore, that, as soon as they see he hath given up the ghost…they shall give orders to have those that are in custody shot with their darts....” So they promised him not to transgress his commands…

With his imminent death clear to him, the day after his return from Jericho, on Tuesday, March 20, Herod sent out a summons calling for all of the “principal men” of the Jews to come to him at Jericho. Most, if not all, of these distinguished men were probably Sanhedrin members living in the environs of Jerusalem, less than a day’s journey away, so they could have arrived and been shut into the hippodrome by Friday, March 23, just before the Sabbath began with its travel restrictions. Thereupon Herod instructed his sister Salome and her husband to ensure his death was accompanied by national mourning by making arrangements for the incarcerated to be killed, which of course they agreed to do. We continue the narrative, including Whiston's quaint archaic spellings:

As he was giving these commands to his relations, there came letters from his ambassadors, who had been sent to Rome, unto Cesar…”as to Antipater himself, Cesar left it to Herod…either to banish him, or to take away his life….” When Herod heard this, he was somewhat better…at the power that was given him over his son. But as his pains were become very great…he called for an apple, and a knife…and had a mind to stab himself with it…his first cousin Achiabus prevented him, and held his hand, and cried out loudly. Whereupon a woful lamentation echoed through the palace, and a great tumult was made, as if the King were dead. Upon which Antipater…discoursed with the jaylor about letting him go…. But the jaylor did not only refuse to do what Antipater would have him, but informed the King of his intentions…. Hereupon Herod…sent for some of his guards, and commanded them to kill Antipater without any farther delay...

Still on Friday, March 23, as Herod was making plans with Salome and Alexas, word arrived from Caesar allowing him to put his son Antipater to death. The travel involved would have been at the end of winter, probably using the first available ship south after sea travel resumed. He apparently got an adrenaline high from this news that helped him feel better, but it was very short-lived. The day after the Sabbath, on Sunday, March 25, after the euphoria had worn off and his pains were felt more sharply than ever, he was of a mind to end it all in suicide, but the effort was foiled by a quick-thinking cousin. But the ensuing household clamor over the attempt reached the ears of Antipater in his jail cell, was misinterpreted as death wails, and his lust for the kingship became Antipater’s final undoing. His attempt to manipulate the jailor into releasing him reached Herod’s ears immediately, and was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. Antipater was summarily put to death that same day.

And now Herod altered his testament…he appointed Antipas, to whom he had before left the Kingdom, to be tetrarch of Galilee and Perea: and granted the Kingdom to Archelaus. He also gave Gaulonitis, and Trachonitis, and Paneas to Philip…. When he had done these things, he died, the fifth day after he had caused Antipater to be slain: having reigned since he had procured Antigonus to be slain thirty four years: but since he had been declared King by the Romans thirty seven.

Herod wasted no time changing his will once more, deciding to grant the kingdom to Archelaus rather than Antipas as the previous will had specified. Just a day or two at most was needed to write and ratify the changed will. His death being expected sooner rather than later, surely by this time his family would have already begun plans for his funeral, so that after he died all that remained was to implement them. And thus, five days after executing Antipater, Herod went to join his son in the early spring of 4 BC, 34 inclusively-counted years from the 37 BC start date for his reign that we previously built a case for.

By the timetable proposed, therefore, Herod would have died on Friday, March 30, 4 BC. This would correspond to Nisan 2 on the Jewish calendar. Recall our previous discussion about calendar matters and what the Mishnah said:

On the first of Nissan is the [cut off date for the] New Year regarding [the count of the reigns of the Jewish] kings [which was used to date legal documents. If a king began his reign in Adar even if was only for one day that is considered his first year, and from the first of Nissan is considered his second year…] (http://www.emishnah.com/moed2/Rosh_HaShanah/1.pdf; brackets with summarized Gemara commentary original, emphasis added).

Thus, having passed Nisan 1, we have entered the 34th year of Herod’s de facto reign on the inclusively-reckoned Jewish calendar Josephus clearly indicated he preferred. Though it is tight, it nevertheless fits. If instead we had followed Harold Hoehner’s thesis (“The Date of the Death of Herod the Great,” Chronos, Kairos, Christos: Nativity and Chronological Studies Presented to Jack Finegan, pp. 103–105) that Herod (and Josephus) reckoned his regnal years using a Roman calendar with January 1 as the start of the year rather than Nisan 1, there would have been plenty of time to spare. Against this, however, is the fact that nowhere in Antiquities or Wars does Josephus use a Julian date. Though not fatal for Hoehner’s thesis (Josephus often dates things by consular years, which generally began on January 1) it is nevertheless somewhat problematic, and one of the reasons why being able to make the case with the much tighter Jewish calendar in view is more persuasive.

At this point, then, we have 13 days until the Passover festival begins on Nisan 15. Can the remaining events of the funeral and mourning period be fit in before the Passover arrives on April 12? We take up the story at Antiquities 17.8.2:

But then Salome and Alexas, before the King’s death was made known, dismissed those that were shut up in the hippodrome…. And now the King’s death was made publick: when Salome and Alexas gathered the soldiery together in the amphitheatre at Jericho. And the first thing they did was, they read Herod’s letter, written to the soldiery; thanking them for their fidelity and good will to him; and exhorting them to afford his son Archelaus, whom he had appointed for their King, like fidelity and good will. After which Ptolemy, who had the King’s seal intrusted to him, read the King’s testament: which was to be of force no otherwise than as it should stand when Cesar had inspected it…

Not sharing Herod’s mania, at his death Salome and Alexas did the compassionate thing and promptly released the distinguished prisoners in the hippodrome. The soldiers were doubtless informed later the same day, March 30, of Herod’s death, and his final will was immediately read, with its stipulation that Caesar had to give his final approval before it was official. Antiquities 17.8.3 then continues:

After this was over, they prepared for his funeral: it being Archelaus’s care that the procession to his father’s sepulchre should be very sumptuous. Accordingly he brought out all his ornaments, to adorn the pomp of the funeral. The body was carried upon a golden bier, embroidered with very precious stones, of great variety.... About the bier were his sons, and his numerous relations. Next to these was the soldiery...every one in their habiliments of war. And behind these marched the whole army, in the same manner as they used to go out to war.... These were followed by five hundred of his domesticks, carrying spices. So they went eight furlongs [stades] to Herodium. For there, by his own command, he was to be buried. And thus did Herod end his life (brackets added).

The pomp and circumstance befitting the passing of a king was implemented for his father by Archelaus. As mentioned earlier, Ernest Martin, in trying to make a case to move the death of Herod to 1 BC, pads his timeline with many imagined causes for delay. Here is an example:

Josephus said the “whole army” was represented in the procession. For military commanders of the armed forces located throughout the realm to be summoned to Jericho and given time to arrive would have taken several days, at least a week and probably longer. There were few pre-arrangements for a massive funeral procession that Josephus said took place since Herod at first believed he could find a cure of his sickness while at his winter home in Jericho. But elite units of the army were not the only ones summoned to Jericho for the procession. It would also have taken some time for the relatives of Herod and other political and religious leaders of the realm (as well as representatives of neighboring nations) to arrive for the procession. These military commanders and other political luminaries gathering at Jericho would have taken a week or so (http://askelm.com/star/star010.htm).

These suggestions appear to be overkill. Since Herod’s death was expected soon after his return from Callirrhoe, immediately beginning to plan for it makes sense. Every needful thing not already in Jericho was just a day away in Jerusalem—the relatives, any servants who were not already in Jericho, the key military figures, the bulk of the troops, even what Martin calls the “crown jewels”—so everything could be set up fairly quickly. Doubtless the approach of the Passover and its impact on a large funeral figured into the plans as well, so they would want to get the burial concluded before that festival arrived. Furthermore, the province of Judea was not important enough in the grand scheme of things to warrant the presence of other heads of state at the funeral, so no significant delay to accommodate the arrival of foreign dignitaries was necessary. “The whole army” need not mean soldiers from throughout the realm, for surely defenders would have remained at their garrisons in important locations, even in Jerusalem where Herod had made many enemies and where rabble-rousers were a potential problem (as Archelaus’ experience following the funeral demonstrated). It makes good sense for “the whole army” to simply refer to all the soldiers who made it to Jericho by the time the other funeral preparations were complete. The bulk of the soldiers would doubtless have been posted nearby at Jericho and Jerusalem. Only three days might have been sufficient for all of the necessary arrangements to have been made.

Then the day of the funeral came, when “they went eight stades toward Herodeion,” a short but full funeral procession with many people involved. This would have taken up several hours on a single day, at which point the public funeral was over and the body conveyed at military march by the army to the Herodium for entombment—there is no reason to join Martin in his conjecture supposing a period of lying in state at Jerusalem. Thus, if Herod died on March 30, his funeral could have taken place on Monday, April 2. The timeline proposed is reasonably generous in the amount of time allocated to the visit to Callirrhoe; if the time spent there was shorter due to the oil immersion scare, his death could have been earlier.

Now Archelaus paid him so much respect, as to continue his mourning till the seventh day. For so many days are appointed for it by the law of our fathers. And when he had given a treat to the multitude, and left off his mourning, he went up into the temple.

Here we learn that Archelaus was able to fulfill the seven days of shivah, the mourning period, prior to the Passover. Shivah would have started the day of Herod’s burial. If burial took place on Tuesday, April 3, it would have extended through Monday, April 9, three days before the seven-day Feast of Unleavened Bread would begin.

He had also acclamations and praises given him which way soever he went: every one striving with the rest who should appear to use the loudest acclamations. So he ascended an high elevation made for him, and took his seat in a throne, made of gold: and spake kindly to the multitude…. Whereupon the multitude, as it is usual with them, supposed that the first days of those that enter upon such governments declare the intentions of those that accept them: and so by how much Archelaus spake the more gently and civilly to them, by so much did they more highly commend him, and made application to him for the grant of what they desired…. Hereupon he went and offered sacrifice to God: and then betook himself to feast with his friends.

It is here suggested that Archelaus entered the Temple early on the day after his shivah period ended, on Tuesday, April 10. At this time he offered public thanks to the people for their warm greeting, offered sacrifice to God, “and then betook himself to feast with his friends.” This feast marked the end of his mourning period and return to public life.

But there was to be no honeymoon period. As Antiquities 17.9.1–2 informs us:

At this time also it was, that some of the Jews…lamented Matthias, and those that were slain with him…for pulling down the golden eagle…. These people assembled together, and desired of Archelaus, that…he would deprive that High Priest whom Herod had made; and would choose one more agreeable to the law, and of greater purity, to officiate as High Priest. This was granted by Archelaus: although he was mightily offended at their importunity: because he proposed to himself to go to Rome immediately, to look after Cesar’s determination about him. However, he sent the General of his forces to use persuasions, and to tell them…that the time was not now proper for such petitions; but required their unanimity, until such time as he should be established in the government by the consent of Cesar; and should then be come back to them. For that he would then consult with them in common, concerning the purport of their petitions.... But they made a clamour, and would not give him leave to speak…. The sedition also was made by such as were in a great passion: and it was evident that they were proceeding farther in seditious practices, by the multitude’s running so fast upon them.

The above activities seem to have taken place later the same day Archelaus feasted with his friends: “at this time also…” Those who had lost relatives at the Jericho trial, just four weeks earlier, assembled and pressed Archelaus for immediate action to remove Joazar (Ant. 17.6.4), the successor to the deposed high priest Matthias. This being grudgingly granted, the day closes with Archelaus asking the people to have patience for Caesar to approve Herod’s will and properly install him in the kingship, and then their demands for a full hearing about their complaints would be granted.

Now we come to the conclusion of this passage we’ve been examining in detail, with the goal of seeing if all the events Josephus covers could fit into the available time between the eclipse and the Passover, Antiquities 17.9.3:

Now upon the approach of that feast of unleavened bread…called the Passover…the seditious lamented Judas and Matthias, those teachers of the laws; and kept together in the temple…. And as Archelaus was afraid lest some terrible thing should spring up by means of these mens madness, he sent a regiment of armed men, and with them a captain of a thousand, to suppress the violent efforts of the seditious; before the whole multitude should be infected with the like madness…. But those that were seditious on account of those teachers of the law, irritated the people by the noise and clamour they used to encourage the people in their designs. So they made an assault upon the soldiers…. So he [Archelaus] sent out the whole army upon them…. Then did Archelaus order proclamation to be made to them all; that they should retire to their own homes. So they went away, and left the festival; out of fear of somewhat worse which would follow…. So Archelaus went down to the sea…and left Philip his brother as governor of all things...(brackets original).

The introduction of this passage with “now” implies that, though tensions were running high the previous day, things did not get completely out of hand, and it closed with the general futilely attempting to explain to the people why their aggressive approach in pushing their concerns was self-defeating. The presence of the army seems to have been enough to prevent a riot. But things festered overnight and came to a head the next day, Wednesday, April 11. The words “the approach of that feast of unleavened bread” appear to refer to the day before the start of the seven-day Feast (“the Passover,” taken as a whole), which began on Nisan 15. (The difference between the Feast period and the Passover seder meal date is discussed at How the Passover Illuminates the Date of the Crucifixion.) Thus understood, the “approach” date would have been Nisan 14 (April 11), with the Passover festival officially starting at sunset that day. At length a riot broke out, when the agitators pushing for justice over the golden eagle affair attacked the soldiers, prompting a forceful, doubtless bloody army response and the cancellation of the Passover festival. Having at length dismissed the people and closed down the Passover celebration, Archelaus put his brother Philip in charge of things and left at his earliest opportunity for Rome to seek Caesar’s official blessing on his kingship.

Altogether, then, we can put together the following chart. It shows at a glance that everything Josephus lays out between the eclipse and the following Passover can be fit into the available time in 4 BC, and without violating any Sabbath travel restrictions. That is not to say that the above timeline is correct in every detail—we acknowledge that placement of the various events in the timeline involves some speculation—but it does demonstrate that claims which dogmatically assert the fit is impossible are untrue. Our contention is that this reconstruction is far less speculative than trying to defend a 1 BC date for Herod's death by proposing protracted funeral delays. By that token, 4 BC passes not only all the other more objective criteria for the year of Herod’s death already covered in previous articles in this series, but the criterion of available time for all events to take place at the close of Herod’s life as well.

In passing we mention that, although Ernest Martin is no fan of the March 13, 4 BC eclipse, he gives us a good reason to prefer it over that of September 15, 5 BC. It has to do with Herod’s health and the venue of the trial. Martin points out that Jericho would have been extremely hot in September (http://askelm.com/star/star011.htm):

Herod was in Jericho when the eclipse near his death occurred. The city is a furnace in late summer. It is situated just over 800 feet (c. 240 meters) below sea level and its mid-September temperatures are very high. Why would Herod, who was uncomfortably ill at the time, subject himself to such oppressive conditions in the Jordan Valley when the pleasant environment of Jerusalem was, so near? It might be added, however, that if the eclipse were in the depth of winter, one could easily understand Herod’s wish to be in Jericho. This point alone renders the September 15th eclipse as improbable for consideration.

Information about temperatures at Jericho is readily available on the Internet. At http://www.levoyageur.net/weather-city-JERICHO.html it tells us that in September, Jericho has an average temperature of 29.6°C (85.3°F) and a high of 35.8°C (96.4°F), with scant rainfall. This data supports Martin’s point. So even though his overall thesis must be rejected for its many problems, we should not neglect crediting him for this insight that favors the 4 BC date.

Summary

There remain some loose ends still to cover in considering when Herod the Great died. In particular, there were some points raised by Ernest Martin regarding the sheloshim mourning period observed by Archelaus in the aftermath of Herod’s death; perceived problems in accounting for the observation of Purim right after the trial at Jericho; and how the reigns of the sons of Herod impact how we view the date of Herod’s death. We will discuss these issues soon in Part 2 of this article.