Three Palaces of Biblical Kings Viewed from Google Earth

Bryan Windle

Technology and archaeology have intersected in unprecedented ways since the dawn of the 21st century. Detailed satellite images of the planet now allow archaeologists to view ancient sites in a whole new way. In fact, satellite imagery has led to a whole new field, dubbed space archaeology, which has led to some breathtaking discoveries.1

For the average person, Google Earth’s satellite images provide an interesting way to explore archaeological sites. Here are the palaces of three biblical kings which can be viewed using Google Earth.

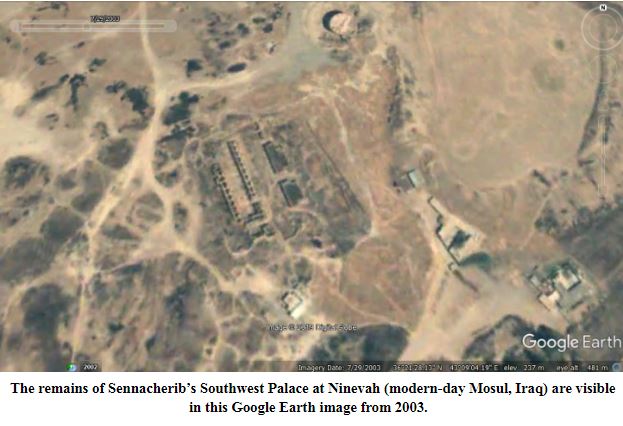

Sennacherib ascended the Assyrian throne around 705 BC and devoted himself to turning Nineveh into a magnificent city and building himself a “palace without rival."2 It remained the capital of the Assyrian empire until the Babylonians sacked the city around 612 BC. In Jonah’s day, Nineveh had a population of 120,000 people who “could not tell their right hand from their left.” (Jonah 4:11)

When Austen Henry Layard excavated at Nineveh in 1847, one of the first buildings he unearthed was the Southwest Palace of Sennacherib, located on the citadel mound of Kuyunjik. It was here that he found the famous reliefs of the siege of Lachish, one of the top discoveries in biblical archaeology.

Sennacherib’s Southwest Palace can be seen on older Google Earth images, before a roof was built over-top of it. The palace’s overall dimensions were an astounding 180 by 190 meters and it contained at least 80 rooms, many of which were lined with sculptures and reliefs. It has been calculated that there were almost 2 miles of reliefs on the walls in Sennacherib’s palace!3 Most of these reliefs and the guardian animals that Sennacherib ordered carved were destroyed by the Babylonians, with only their lowest parts remaining into the 21st century.4

The palace of Sennacherib had been preserved as a museum, with a roof constructed over it and 100 reliefs left in situ. Sadly, when ISIS occupied Mosul (the site of ancient Nineveh), they looted and destroyed Sennacherib’s palace in a way that the Babylonians never could. Recent satellite images taken by Digital Globe/ASOR show that in 2016, ISIS removed the protective roof, tore down the pillars and visible vehicle tracks are proof that they removed most of the valuable material by the truckload.5

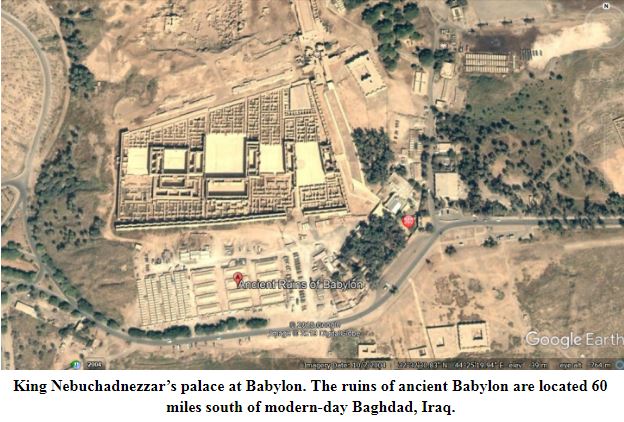

Serious investigation of the ruins of Babylon began in the late 1800’s, first with industrial-scale digging by the British Museum from 1879-1882, and then with systematic and scientific excavations led by Robert Koldewey of the German Oriental Society.6 Beginning in 1899 and continuing for 18 years, Koldewey made numerous discoveries, including the famous blue-bricked Ishtar Gate, the Processional Way which led to the Temple of Marduk, and the Southern Palace of King Nebuchadnezzar.

Nebuchadnezzar himself describes how he rebuilt the palace of his father:

“I tore down its walls of dried brick, and laid its corner-stone bare and reached the depth of the waters. Facing the water, I laid its foundation firmly, and raised it mountain high with bitumen and burnt brick. Mighty cedars I caused to be laid down at length for its roofing. Door leaves of cedar overlaid with copper, thresholds and sockets of bronze I placed in its doorway. Silver and gold and precious stones, all that can be imagined of costliness, splendor, wealth, riches, all that was highly esteemed I heaped up within it, I stored immense abundance of royal treasure within it.”7

During his excavations of the Southern Palace Koldewey discovered a structure in one corner with 14 long rooms laid out in two rows, along with a system of wells and channels nearby. He identified this as the infrastructure of the famed Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Modern scholars have suggested it was a storehouse for oil, grain, dates and spices.8In 1987, Saddam Saddam Hussein came to visit the site of Babylon, located 60 miles south of Baghdad, Iraq. He ordered one of the palaces to be rebuilt, with little regard for the archaeological past which he was erasing. Dubbed “Disney for a Despot” the new “palace” was hastily built over-top of the ancient one out of brinks inscribed with both his name and that of Nebuchadnezzar.9 Fortunately, the remains of the Southern Palace remained largely untouched and are clearly visible in Google Earth images today.

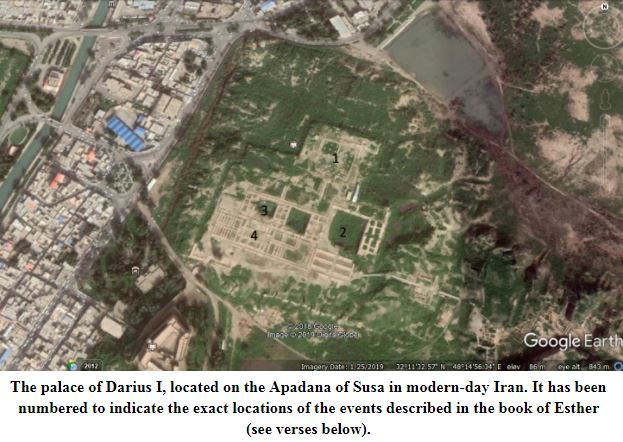

The ancient city of Susa, located in modern-day Iran, served as the winter residence of the Persian kings of the Achaemenid empire. Darius I built his palace on one of the four hills, called the Apadana. His foundation deposit from the palace has been discovered inscribed in three languages: Old Persian, Akkadian, and Elaminte. This inscription is known as the DSf, and its description is remarkably similar to the way the palace is described in Esther 1:5-6.

“The palace which I built at Susa, from afar its ornamentation was brought…the cedar timber, this – a mountain named Lebanon – from there was brought. The Assyrian people, it brought to Babylon; from Babylon the Carians and the Ionians brought it to Susa. The yaka-timber was borught from Gandhara and from Carmania. The gold was brought from Sardis and from Bactria, from here was wrought. The precious stone lapis-lazuli and carnelian which was wrought here, this was brought from Sogdiana. The precious stone turquoise, this was brought from Chorasmia, which was wrought here. The silver and the ebony were brought from Egypt. The ornamentation with which the wall was adorned, that from Ionia was brought. The ivory which was wrought here, was brought from Ethiopia and from Sind and from Arachosia. The stone columns which were wrought, a village by name Abiradu in Elam – from there were brought. The stone-cutters who wroght the stone, those were Ionians and Sardians….Saith Darius the King: At Susa a very excellent work was ordered, a very excellent work was brought to completion.”10

This palace is the setting for the book of Esther, who was married to Darius’s son, Xerxes I (called King Ahasuerus in Hebrew). In fact, the description in the book of Esther is so detailed that one can even identify the places from the Google Earth image where the specific events took place:

- The Audience Hall/Court of the Gardens – “And when these days were completed, the king gave for all the people present in Susa the citadel, both great and small, a feast lasting for seven days in the court of the garden of the king’s palace.” (Esther 1:5)

- The Outer Courtyard – “Later the king said: ‘Who is in the courtyard?’ Now Haman had come into the outer courtyard of the king’s house to speak to the king about having Mordecai hanged on the stake that he had prepared for him.” (Esther 6:4)

- The Inner Courtyard facing the Throne Room – “On the third day Esther put on her royal robes and stood in the inner courtyard of the king’s house, opposite the king’s house…" (Esther 5:1a)

- The Throne Room – “…while the king was sitting on his royal throne in the royal house opposite the entrance.” (Esther 5:1b)

Indeed, these descriptions match the excavated palace so precisely that many scholars have concluded that whoever wrote the book of Esther must have personally spent time there. French archaeologist Jean Perrot was the world’s foremost authority on the ancient palace at Susa, having served as the Director of Excavations there for over a decade. Before his death in 2012 he said, “One today rereads with a renewed interest the book of Esther, whose detailed description of the interior disposition of the palace of Xerxes is now in excellent accord with archaeological reality.”11

ENDNOTES:

1 Space archaeologist, Sarah Parcak, believes she has discovered the ancient Egyptian city of Itj-Tawy – the capital city of the 12th Dynasty Pharaohs (https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2017/01/30/how-new-technology-accelerates-the-search-for-ancient-sites/) This was likely home of Joseph, who lived during that period according to biblical chronology.

2 Max Mallowan, “Ninevah,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. September 6, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/place/Nineveh-ancient-city-Iraq (Accessed April 30, 2019).

3 Howard F. Vos, Archaeology in Bible Lands (Chicago: Moody Press, 1977), 120.

4 “Southwest Palace,” Learning Sites, Inc., December 9, 2016. http://www.learningsites.com/Nineveh/SWP_Nineveh_home.php (Accessed April 30, 2019).

5 Christopher Jones, “The Cleansing of Mosul,” Gates of Nineveh. June 6, 2016. https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2016/06/06/the-cleansing-of-mosul/ (Accessed April 30, 2019).

6 “Koldeway at Babylon,” Current World Archaeology. January 25, 2013. https://www.world-archaeology.com/great-discoveries/koldewey-at-babylon/ (Accessed May 1, 2019).

7 Robert Koldeway, The Excavations at Babylon. (London : Macmillan and Co., 1914), 113. Accessed online: https://archive.org/details/ldpd_10797913_000/page/158 (Accessed May 1, 2019).

8 Juan Luis Montero Fenollos, “Beautiful Babylon: Jewel of the Ancient World” National Geographic History Magazine. January/February 2017. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/archaeology-and-history/magazine/2017/01-02/babylon-mesopotamia-ancient-city-iraq/ (Accessed May 1, 2019).

9 Neil MacFarquhar, “Hussein’s Babylon: A Beloved Atrocity” New York Times, August 19, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/19/world/hussein-s-babylon-a-beloved-atrocity.html (Accessed May 1, 2019).

10 Edwin M. Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), 296.

11 “Shushan The Citadel With Bible In Hand,” Bible Reading Archaeology. September 20, 2018. https://biblereadingarcheology.com/2018/09/20/shushan-the-citedal/ (Accessed May 2, 2019).