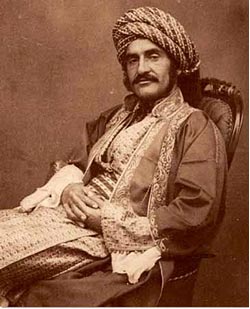

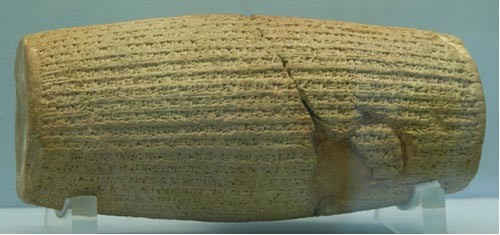

The Cyrus Cylinder is one of the most important discoveries in biblical archaeology. She was aroused from her 2,400-year sleep in the ruins of Babylon in 1879 by Hormuzd Rassam. Rassam, an evangelical Christian, was a native Iraqi born in 1826 in Mosul, across the Tigris River from the remains of ancient Nineveh. He met the famous British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard in 1841. Layard recognized Rassam’s potential and became his patron. Under Layard’s tutelage, Rassam developed into a competent archaeologist, becoming a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, the Society of Biblical Archaeology and the Victoria Institute. In 1876, with the help of Layard, who was now the British ambassador to Turkey, he obtained a permit from the Turkish government to conduct archaeological investigations in Assyria and Babylonia on behalf of the British Museum. From 1876 to 1882 Rassam made an astonishing number of important discoveries not only at Babylon but at other sites such as Balawat, Nimrud, Nineveh and Sippar. According to the BM, he recovered some 134,000 clay tablets and fragments, including the royal library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (Tamras 1997; British Museum 2010c).

Hormuzd Rassam, discoverer of the Cyrus CylinderThe Significance

Hormuzd Rassam, discoverer of the Cyrus CylinderThe Significance

Although broken and incomplete, there were some 36 lines of text still preserved on the Old Lady. She proved to be a foundation text commemorating Cyrus the Great’s capture of Babylon and his subsequent restoration of the city. The date of writing is sometime after the capture of Babylon in 539 BC and Cyrus’ death in ca. 531 BC. And what a story she had to tell! The most important section of her text, from a biblical perspective, is lines 28–35:

At his {Marduk’s} exalted command, all kings who sit on thrones, from every quarter, from the Upper Sea {Mediterranean} to the Lower Sea {Persian Gulf}, those who inhabit [remote distric]ts (and) the kings of the land of Amurru {Syria-Palestine} who live in tents, all of them, brought their weighty tribute into Shuanna {Babylon} and kissed my feet. From [Shuanna] I sent back to their places to the city of Ashur and Susa, Akkad, the land of Eshnunna, the city of Zamban, the city of Meturnu, Der, as far as the border of the land of Guti {mountainous area to the north and east}—the sanctuaries across the river Tigris—whose shrines had earlier become dilapidated, the gods who lived therein, and made permanent sanctuaries for them. I collected together all of their peoples and returned them to their settlements, and the gods of the land of Sumer {southeast Mesopotamia} and Akkad {central Mesopotamia} which Nabonidus {Babylonian king defeated by Cyrus}—to the fury of the lord of the gods—had brought into Shuanna, at the command of Marduk, the great lord. I returned them unharmed to their cells, in the sanctuaries that make them happy. May all the gods that I returned to their sanctuaries, every day before Bel and Nabu, ask for a long life for me, and mention my good deeds (Finkel 2010).

When Cyrus took Babylon, there were many Jewish captives there from Nebuchadnezzar’s conquests of Judah in 605, 597 and 587 BC. According to Isaiah’s prophecy, Cyrus was to be God’s instrument to judge the Babylonians, free the Jews, and rebuild Jerusalem and the Temple:

[I am the Lord] who says of Cyrus, “He is my shepherd and will accomplish all that I please; he will say of Jerusalem, ‘Let it be rebuilt,’ and of the temple, ‘Let its foundations be laid.’...I will raise up Cyrus in my righteousness: I will make all his ways straight. He will rebuild my city and set my exiles free” (Is 44:28; 45:13).

The Cyrus Cylinder establishes beyond doubt that it was Cyrus’ policy to return “them [exiles] to their settlements,” and make “permanent sanctuaries” for the gods of the exiled peoples. Moreover, he returned captured idols “unharmed to their cells, in the sanctuaries that make them happy.” In the case of the Jews, however, since they had no idols, the gold and silver articles taken from the Temple were returned. The specific proclamation pertaining to the Jews is documented in Ezra 6:3–5 (cf. I Chronicles 36:22–23 [= Ezra 1:1–3]):

In the first year of King Cyrus [538 BC], the king issued a decree concerning the temple of God in Jerusalem: Let the temple be rebuilt as a place to present sacrifices, and let its foundation be laid. It is to be ninety feet high and ninety feet wide, with three courses of large stones and one of timbers. The costs are to be paid by the royal treasury. Also, the gold and silver articles of the house of God, which Nebuchadnezzar took from the temple in Jerusalem [in 587 BC] and brought to Babylon, are to be returned to their places in the temple in Jerusalem; they are to be deposited in the house of God.

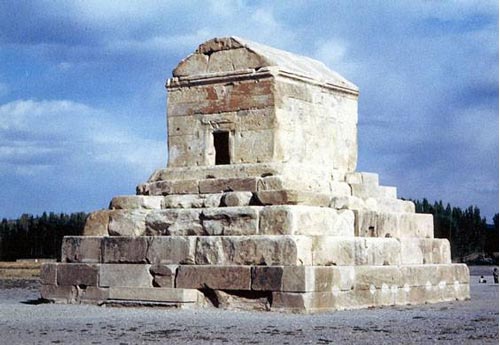

Tomb of Cyrus the Great, king of Persia 559–ca. 531 BC, at his capital of Pasargadae in south-central Iran. (Photo courtesy of Edwin M. Yamauchi)

Tomb of Cyrus the Great, king of Persia 559–ca. 531 BC, at his capital of Pasargadae in south-central Iran. (Photo courtesy of Edwin M. Yamauchi)

In the spring of 1879 Rassam brought the Queen of Texts to London. The Cylinder, written in Akkadian cuneiform, was duly translated and put on display in the BM. End of story, right? Wrong! The Cyrus Cylinder has made the headlines on a number of occasions over the years, right up to the present day. No other ancient artifact has engendered such strong political and emotional passions as the Cyrus Cylinder. At times, she has stirred up international disputes and been something of a “political football”!

The Grande Dame in the News

A Trip to Tehran

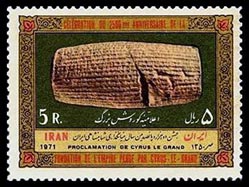

Cyrus Cylinder depicted on an Iranian postage stamp issued October 12, 1971, to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian monarchy. (Source: www.niasnet.org/iran-history/artifacts-historical-places-of-iran/cyruscylinder)Cyrus and the Cyrus Cylinder are regarded with intense national pride in Iran. The Cylinder is part of the country’s cultural and national identity. In 1968, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi opened the first United Nations Conference on Human Rights in Tehran by saying that the Cyrus Cylinder was the precursor to the modern Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In 1971 Iran adopted her as the symbol for a commemoration held October 12–19 to celebrate 2,500 years of Persian monarchy. For the first time the BM allowed the Old Lady to leave the hallowed halls of the museum to travel to the homeland of her namesake, but not without resistance. The Shah had expressed his desire to borrow the precious artifact through the British ambassador, but the suggestion was rejected by the Foreign Office. The ambassador even went so far as to suggest the artifact be given to Iran to gain diplomatic and military cooperation from the Shah’s government. The museum declined the gift idea, but went ahead with the loan, infuriating British officials (Jury 2004).

Cyrus Cylinder depicted on an Iranian postage stamp issued October 12, 1971, to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian monarchy. (Source: www.niasnet.org/iran-history/artifacts-historical-places-of-iran/cyruscylinder)Cyrus and the Cyrus Cylinder are regarded with intense national pride in Iran. The Cylinder is part of the country’s cultural and national identity. In 1968, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi opened the first United Nations Conference on Human Rights in Tehran by saying that the Cyrus Cylinder was the precursor to the modern Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In 1971 Iran adopted her as the symbol for a commemoration held October 12–19 to celebrate 2,500 years of Persian monarchy. For the first time the BM allowed the Old Lady to leave the hallowed halls of the museum to travel to the homeland of her namesake, but not without resistance. The Shah had expressed his desire to borrow the precious artifact through the British ambassador, but the suggestion was rejected by the Foreign Office. The ambassador even went so far as to suggest the artifact be given to Iran to gain diplomatic and military cooperation from the Shah’s government. The museum declined the gift idea, but went ahead with the loan, infuriating British officials (Jury 2004).

The Belle of Babylon was on display in Tehran throughout the week, giving Iranians a rare opportunity to view this important relic of their heritage in their native land. On October 12

a stamp was issued featuring a picture of her and on October 14 the Shah’s sister Princess Ashraf Pahlavi presented the UN with a replica of the Cylinder. Secretary General U Thant accepted the gift, linking it with the efforts of the UN General Assembly to address “the

question of Respect for Human Rights in Armed Conflict.” The replica of the Old Girl is on

display at the UN with a translation in all six official UN languages (Wikipedia 2010). Her

message of human rights is once again being heard around the world.

Cyrus Cylinder on display at the United Nations. (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_CylinderA Chip Off the Old Block

Cyrus Cylinder on display at the United Nations. (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_CylinderA Chip Off the Old Block

In 1920 Rev. J.B. Nies, a clergyman from Brooklyn, purchased a clay cuneiform fragment measuring 3.4 in (5.6 cm) by 2.2 in (5.6 cm) from an antiquities dealer. Upon Nies’ death in 1922 it was bequeathed, along with many other tablets and antiquities he had collected, to the Yale University Babylonian Collection. In 1970 Paul-Richard Berger of the University of Münster recognized that the fragment was part of the Cyrus Cylinder. The piece was joined with the main inscription in 1972, after the Diva of Digs returned from her adventures in Iran (Wikipedia 2010).

Things were quiet for the Grande Dame for the next 30 or so years, but then she began hearing rumblings of another trip to Iran. Could it be possible? Maybe, but this time she would be embroiled in the biggest controversy of her long and usually quiet life. The BM was making plans for the exhibition “Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia,” from September 9, 2005, to January 8, 2006, and needed some antiquities from Iran. So a deal was struck. If Iran would loan the BM 50 artifacts for the exhibition, the BM would loan the Cyrus Cylinder to the

National Museum of Tehran following the exhibition (Jury 2010).

Another Copy?

The loan was held off until a suitable exhibition area could be prepared in the Iran museum. Finally, arrangements were in place for the Cylinder to go on display in September 2009. But it was not to be. First came the unrest following the June 2009 election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, prompting the BM to postpone the loan, citing security concerns. The loan was rescheduled for January 16–May 16, 2010. Then, on December 31, Wilfred Lambert, a retired professor from Birmingham University, was going through some tablets at the BM when he came upon a fragment he realized had a portion of the Cyrus Cylinder on it. This was quickly followed by the discovery of a second fragment from the same tablet on January 5 by BM curator Irving Finkel, who had begun his own search among the 200,000 unpublished tablets in the museum’s collections. As with the Cyrus Cylinder, the fragments had been excavated by Hormuzd Rassam, but in this case not at Babylon but at Dailem south of Babylon. Finding fragments of a tablet with the text of the Cyrus Cylinder was an extremely important development, causing the BM to once again postpone the loan of the Cylinder.

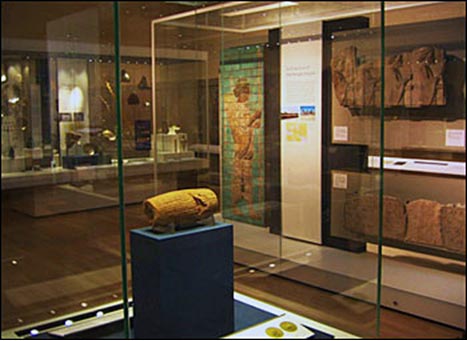

The Cyrus Cylinder on display in the Ancient Iran room of the British Museum. (http://www.iranchamber.com/history/cyrus/cyrus_charter.php)ge615

The Cyrus Cylinder on display in the Ancient Iran room of the British Museum. (http://www.iranchamber.com/history/cyrus/cyrus_charter.php)ge615

One of the newly discovered fragments clarifies a passage in the Cylinder’s message, while the other provides a portion of a previously missing text. Did the Lady spawn offspring, or was she the daughter of an earlier proclamation? Scholars had previously carped that the Cyrus Cylinder was not an edict as such, but a dedicatory text, probably a foundation deposit laid to commemorate Cyrus’ restoration of the temple of Marduk. The Bible specifically states that Cyrus issued a qôl, proclamation (2 Chr 36:23; Ezr 1:1), or ṭaϲam, decree (Ezr 6:3). Is the Bible wrong? Certainly not! This new evidence indicates that Cyrus issued an edict which went beyond Babylon. Later, when the text of the Cyrus Cylinder was drawn up, the proclamation was incorporated.

An official statement made by the BM reads:

Remarkably, the new pieces assist with the reading of passages in the Cylinder that are either missing or are obscure, and therefore help improve our understanding of this iconic document. In addition, they show that the ‘declaration’ on the Cylinder is much more than a standard Babylonian building inscription. It was probably an imperial decree that was distributed around the Persian empire, and it may have been pronouncements of this sort that the author of the Biblical book of Ezra was able to draw upon when writing about Cyrus (British Museum 2010a).

In January the BM scheduled a workshop for June 23–24 to discuss the discovery with other scholars and access the significance of the newly-discovered fragments. On February 2 the trustees of the BM notified Iran that they would lend both the Cyrus Cylinder and the new tablet fragments to Tehran in late July (British Museum 2010a). This did not sit well with Iranian officials. In protest, Iran cut ties with the BM on February 7, including the curtailment of further visits by British archaeologists to Iran (Pouladi 2010). This was followed on April 19 by a demand that the British Museum pay Iran $300,000 for expenses associated with preparations to display the Cylinder (Dahl 2010).

The Cyrus Cylinder, discovered in 1879 in Babylon by Hormuzd Rassam. It is 9 in (22.5 cm) in length and 4 in (10 cm) in diameter, with 45 lines of preserved text. Some of the lines are incomplete and there are a number of missing lines. (Photo by ABR photographer Michael Luddeni)

The Cyrus Cylinder, discovered in 1879 in Babylon by Hormuzd Rassam. It is 9 in (22.5 cm) in length and 4 in (10 cm) in diameter, with 45 lines of preserved text. Some of the lines are incomplete and there are a number of missing lines. (Photo by ABR photographer Michael Luddeni)

Them Bones, Them Bones, Them Dry Bones

Amid all this political turmoil, there has been yet another development related to our Belle of Babylon. In a June 24 BM press release notifying the public of a lecture following the June workshop, it was announced,

two Chinese ‘cuneiform bones’ which have usually been seen as forgeries are ancient copies of an otherwise unknown duplicate of the Cyrus inscription (British Museum 2010b).

The “cuneiform bones” referred to in the announcement are two fossilized horse bones found in China with cuneiform letters inscribed on them. Strangely, the texts have less than one in every 20 of the Cyrus text’s cuneiform signs transcribed, although they are in the correct order. The bones were acquired by Xue Shenwei, a Chinese traditional doctor. He said he had learned about the pair of inscriptions in 1928. He bought the first bone in 1935 and the second in 1940, and named the sellers. Xue bought them because he thought they were written in an unknown ancient script, presumably from China. In 1966, during the Cultural Revolution, he buried the bones for protection, digging them up later. Chinese scholars who have pursued the story believe that Xue’s account is credible.

In 1983 Xue brought the bones to the Palace Museum in the Forbidden City in Beijing, which collects inscriptions. It was then that specialists told him they were written in cuneiform. In 1985 he donated the bones to the Museum, then died shortly thereafter. Specialist Wu Yuhong at the Museum was the first to understand that the text of the first bone came from a proclamation identical to that of the Cyrus Cylinder.

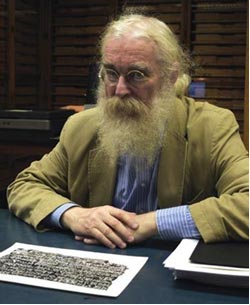

Following the discovery of the two tablet fragments, Finkel turned his attention to the Chinese bones. It had been thought that they were forgeries, but he wondered if they might be authentic. He determined that the text on the second bone was also from the Cyrus proclamation and requested more information from Beijing. Chinese Assyriologist Yushu Gong went to the Palace Museum storerooms to examine the bones, and also arranged for a new rubbing of the inscriptions (done with black wax on paper), which would provide a much better image of the text than existing photographs. Yushu took the rubbings to London for the June workshop. Irving Finkel and the rubbing of the fossilized Chinese horse bones with cuneiform writing

Irving Finkel and the rubbing of the fossilized Chinese horse bones with cuneiform writing

(The Art Newspaper).

The obvious question is whether the inscriptions are forgeries—although they would be bizarre objects to fake. Why would a faker use fossilized horse bone, a material never used before for this purpose? If the bones had indeed been acquired by Xue by 1940, it would not have been easy for a Chinese forger to have gained access to the Cyrus text, which only became widely known later in the 20th century. Why would a faker have carved only one in 20 of the characters, which meant that it took years before the Cyrus text was identified? And why would a faker have sold the bones in China, where there has been virtually no market for non-Chinese antiquities?

The clinching factor for Finkel is that the partial text on the bones differs slightly from that on the Cyrus Cylinder, although it is correct in linguistic terms. Cuneiform changed over the centuries, and the signs on the bones are in a less evolved form than that of the Cylinder. The individual wedge-like strokes of the signs are also different and have a slightly v-shaped top, a form that was not used in Babylon, but was used by scribes in Persia.

“The text used by the copier on the bones was not the Cyrus Cylinder, but another version, probably originally written in Persia, rather than Babylon,” said Finkel. It could have been a version carved on stone, written with ink on leather, or inscribed on a clay tablet. Most likely the

original object was sent during the reign of Cyrus to the far east of his empire, in the west of present-day China.

Scholars at the workshop had little time to digest the new evidence, and inevitably there was some skepticism. But Finkel concludes that the evidence is “completely compelling.” He is convinced the bones were copied from an authentic version of the Cyrus proclamation, although it is unclear at what point in the past 2,500 years the copying was done (Bailey 2010).

Human Rights Legislation

The Cyrus Cylinder is touted as the world’s first proclamation of human rights. Certainly it is unique among ancient texts, but what about the Bible? God gave Moses comprehensive human rights legislation addressing the rights and needs of the poor and underprivileged at Mount Sinai some 900 years before the Cyrus Cylinder. It provides a legal system to dispense justice (Ex 23:1–8; Dt 16:18–20; 17:8–13; 25:1–3) and establishes rights for the poor (Ex 22:25–27; 23:6; Dt 15:1–11; 24:14–15); women (Ex 22:16–17; Dt 21:10–15; 22:13–30); widows and orphans (Ex 22:22–24; Dt 24:17–22); slaves, both male and female (Ex 21:2–11; Dt 15:12–18; 23:15–16), and aliens (Ex 22:21; 23:9; Dt 24:17–22). In contrast, other ancient near eastern law codes dealt with property rather than people.

From these new discoveries it seems clear that Cyrus issued a general edict freeing the captives in Babylon and restoring their religious institutions, which was disseminated throughout the empire. The edict was later included in the Cyrus Cylinder foundation text. What will be the next discovery relating to the Cyrus Cylinder? Only God knows. In the meantime the Grande Dame of ancient inscriptions will continue to hold court in the Ancient Iran room of the BM where millions of visitors come to see her each year.

Bibliography

![]() The-Ongoing-Saga-of-the-Cyrus-Cylinder--The-Internationally-Famous-Grande-Dame-of-Ancient-Texts.pdf

The-Ongoing-Saga-of-the-Cyrus-Cylinder--The-Internationally-Famous-Grande-Dame-of-Ancient-Texts.pdf