Introduction

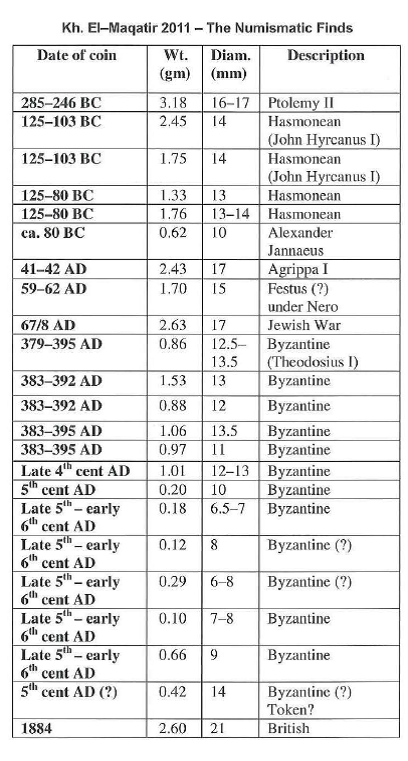

Few things are more exciting at an archaeological excavation than finding coins, probably because they provide a direct and tangible connection with history. There is often writing on these coins, which is an important factor in archaeology because a readable coin can help to date the stratum in which it was found. On June 1, 2011, my team in Field C at Khirbet el-Maqatir found nine coins; eight of them were from a single locus inside the central apse of the church. Three other coins were found in an Early Roman house on the east end of the site. In December 2011, another eleven coins were recovered. The table below provides the details of these 23 coins.

The Maqatir Coins

The oldest coin was from the mid-third century BC (Ptolemy 11, 285-246 BC), and the most recent was a British coin from the 19th century. This range of dates spanning two millennia yet appearing in the same stratum requires some explanation since the assumed dates for the ecclesiastical complex are from the fourth to the sixth century. The initial pottery readings and the coin dates confirm this. Thirteen of the coins date to the Late Roman or Byzantine timeframe. Six of the coins are from the three centuries before Christ. Five of the six were minted by the Hasmonean rulers. Three of the coins were from the first century AD, including a coin of Porcius Festus (Acts 26) and a coin from Year Two of the First Jewish Revolt. The final first century coin, the focus of this article, was minted by Herod Agrippa I; it was the first from the New Testament period to be found at Khirbet el-Maqatir after nine seasons of excavation. Previously, coins were limited to the lntertestamental Period, the latest being a coin of Herod the Great that was dated to his third year as king, 37 BC. 1

Agrippa I, grandson of Herod the Great, was the son of Aristobulus IV and Bernice and father of Agrippa II (Acts 25-26); he ruled as king over much of his grandfather's realm from AD 37 to 44. The Agrippa I coin dates to the sixth year of his reign, AD 41/42. Agrippa I was in many ways an enigma. He was a close friend of Emperor Caligula (AD 37-41) and also enjoyed the favor of Claudius, who came to the throne in AD 41. Claudius was emperor when the Maqatir coin was struck. Agrippa I minted coins bearing the images of these Caesars and various pagan likenesses. On the other hand, he went to great lengths to maintain peace with the local Jewish population. He persuaded Caligula to abandon his bizarre intentions to erect a statue of himself in the Jerusalem temple (Josephus, Ant. 18.8.2-9). Agrippa I also ingratiated himself with the Jewish leaders by ignominiously becoming the first ruler to persecute the nascent Christian Church (Acts 12:1-3). This was certainly in keeping with the policies of Emperor Claudius, who, according to Acts 18:2, expelled all Jews (traditional and Messianic) from Rome. In The Twelve Caesars, Suetonius poignantly confirms that "there were continual uprisings on account of Chrestus" (Life of Claudius 25.4). Chrestus is a reference to Christ.2

Agrippa's title on the obverse (front) of the coin is BASILEUS, the Greek word for "king." This title is in keeping with the Roman custom of lauding the ruler who issued a coin, and not surprisingly, was the exact title attributed to him in Acts 12:1. The reverse of Roman coins was normally for propaganda purposes, but Agrippa, as a client king, wisely placed on it three ears of barley, a traditional Jewish symbol.

The Mishnah records that during the Feast of Tabernacles in AD 41 he publically read Deuteronomy 17:15, which states, "You may not put a foreigner over you who is not your brother." When Agrippa, who like all of the Herodian rulers was only part Jewish, began to weep, the people responded, "Grieve not, Agrippa; you are our brother! You are our brother!" (Sotah 7:8). This sort of adulation led to Agrippa's gruesome death at Caesarea Maritima in AD 44 at the tender age of thirty-four. After a speech, perhaps in the still standing amphitheatre, the crowd proclaimed that his words were those of a god (clearly idolatry), and "because Herod did not give praise to God, an angel of the Lord struck him down, and he was eaten by worms and died" (Acts 12:23). Interestingly, the same event was recorded by the Jewish historian Josephus (Ant.19.8.2), producing a fascinating and important synchronism between biblical and secular texts.

Circulation of Ancient Coins

All of this is informative, but it begs the question, What is a first century coin doing in a fourth to sixth century conobium-type monastery?3 There are four possible explanations for this seemingly odd occurrence. First, one of the monks may have been a coin collector. This is pure speculation and highly unlikely. Second, maybe the monastery and church are much older than at first thought. Although recent discoveries of early churches at places like Megiddo (ca. 230) have forced a rethinking of the transition from the domus ekklesia, or house church, to basilicas, or public buildings devoted to Christian worship, this second possibility also seems unlikely, especially with the appearance of a possible side apse indicating a later church (Tsafrir 1993: 12). Third, the early coins may have been part of the fill used to level out the area upon the jagged bedrock to create a flat surface for the church and monastery. Most of the early coins came from below floor level (2,914 ft. [888.23 m]), but some were found above floor level. This could be explained by scavenging or earthquake damage. Third, in Roman and Byzantine times coins may have remained in circulation for hundreds of years. This appears to be the most plausible explanation. Classical numismatist David Yagi cites examples of this prolonged circulation:

It is well-documented both by literary and archaeological evidence that ancient coins often circulated for centuries. An excellent example is the countermarking of older, worn coins in the east by the emperor Vespasian in the early A.D. 70s. The majority of these denarii were at least a century old at the time they were countermarked. The issuance of Imperial cistophori by the emperor Hadrian (117-138) is similarly convincing. Most (if not all) of the planchets used were older cistophori issued some 100 to 150 years earlier. We have no reason to doubt that these "host" coins (the coins that were overstruck) had been in circulation up until the time they were withdrawn for re-coining. (1999: 19-20)

Furthermore, a bronze coin of Domitian (AD 81-96) was in circulation in Spain until 1636, when it was re-coined in the financial reforms of Philip IV (Blanchet 1907: 26). Coins minted under Constantine (AD 323-337) were still circulating in parts of southern France during the reign of Napoleon III (1852-1870) (Friedensburg 1926: 3). Due to the high inflation of the third century AD, older Roman coinage appears to have been used much longer than contemporary money. The coinage from Pompeii confirms that a significant number of Republican coins (prior to Julius Caesar) were still in circulation at the time the city was buried by the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, and they remained in circulation for another 30 to 40 years (Harl 1996: 18). This is over 150 years altogether.

The Agrippa I coin, like all bronze coins, would have remained in use much longer, especially in the provinces, than its gold and silver counterparts previously mentioned (Harl 1996: 257). So, it is certainly possible, indeed probable, that the Agrippa I coin had remained in circulation for four centuries. However, it seems to stretch the limits of plausibility to assume that the third century BC coin found in the same stratum could have remained in continual circulation. As always, archaeology raises as many questions as it answers.

Conclusion

In an ironic twist of fate, Agrippa I, who died because of his refusal to give glory to God, is 2,000 years later buttressing the historicity of the biblical narrative. Many more coins are under the accumulated debris of millennia, just waiting to tantalize us with their mysterious stories. Maybe you can be the volunteer who finds the next one!

Notes

1 See Wood, Bryant G. Three Coins from a Mountain. Bible and Spade 11.4: 86-90.

2 Other early references can be found in the following sources: Josephus (Antiquities, 18.3.3), Tacitus (Annals, 15.44.3), and Pliny the Younger (Epistles, 10.96-97).

3 Ascetic monasteries are referred to as laura, and communal monasteries as conobium.

Bibliography

Blanchet, Adrien J. 1907. Sur La Chronologie etablie Par Les Contremarques. Paris: Rolin.

Danby, Herbert. 2008. The Mishnah. Oxford: Oxford University.

Friedensburg, F. 1926. Die Munze in der Kulturgeschichte. 2nd ed. Berlin.

Harl, Kenneth W. 1996. Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to AD 700. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

Josephus, Flavius. 2006. Antiquities of the Jews. West Valley City UT: Waking Lion.

Suetonius, and Rolfe, John Carew. 2008. The Twelve Caesars: the Lives of the Roman Emperors. St. Petersburg FL: Red and Black.

Tsafrir, Yoram. 1993. Churches in Palestine: From Constantine to the Crusaders. Pp. 1-16 in Ancient Churches Revealed. Washington DC: Biblical Archaeological Society.

Yagi, David L. 1999. Coinage and History of the Roman Empire. Vol. 11. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn.

Read Scott Stripling's full article via PDF: Maqatir-Monastery-Money-_Dr-Scott-Stripling.pdf

This article was originally published in Bible and Spade Vol. 25 No. 2 (Spring)