The question is often asked, “Does archaeology throw any light on the New Testament?” The answer, of course, is “Yes.” But it stands to reason that there will not be as much new information about the New Testament as there has been regarding the Old Testament. The period of the Old Testament extended for thousands of years, whereas the writings of the New Testament are confined to the first century A.D.

In this article we shall consider only one way in which archaeology has added its testimony to the accuracy and background of the New Testament. We shall glance at one of the most challenged of all the New Testament writings – the Acts of the Apostles.

The Challenge Against Luke

According to the New Testament itself, Luke was a physician and wrote the Acts of the Apostles as well as the Gospel bearing his name. But many scholars of a generation past claimed that the Acts of the Apostles were the work of a much later hand. German scholars of the famous Tubingen school were especially outspoken against Luke’s genuineness. The argument of many was that someone wrote these documents at least a century, and possibly two centuries, after the time of Luke. But now there is not such confident criticism, largely because archaeological evidence has come forth to support the claim that Acts was written by an eyewitness.

For instance, Acts 6:9 mentions the Synagogue of the Libertines. This was a synagogue for the “liberated ones,” the “freedmen.” We now know that there were literally hundreds of synagogues for various groups of people in Jerusalem at this time – there was the Synagogue of the Weavers, the Synagogue of the Embroiderers, and many others. We know from archaeological evidence that there was a strong trade union movement in the time of our Lord. These trade unions were formed for two main reasons; first, to get the obvious benefits of association in manufacturing and trading activities; and, secondly, to provide a basis for fellowship and social life. One important aspect was the provision of suitable arrangements for a decent burial. Otherwise it was all too likely that poorer people would be buried simply by being tossed in to a hole dug in the earth – a most unacceptable burial for pious Jews. People with similar interests and activities came together in a way that was not unlike the functions of unions today. They did not strike for better wages, however. If they did they would simply have lost their jobs, for laborers were all too easily obtained in those days.

There were also Jewish synagogues for those who belonged to groups other than trade unions. Thus we are not surprised to find Luke’s reference to the Synagogue of the Libertines at Acts 6:9. An inscription dating to New Testament times has been found in this very area, making it clear that there was indeed a special synagogue for these Libertines, or “freedmen” as the word means.

But the most wonderful social fellowship of the times was that known by followers of Jesus Christ. Spiritually they became brothers, with a new hope entirely superior to the other social groups of the first century A.D.

The Goddess Diana

There are many other places and buildings to which Luke refers, which are now known to have been correctly described. He knew that Lystra and Derbe and certain neighboring territories comprised a special region, as is made clear by his reference in Acts 14:6: “they learned of it and fled to Lystra and Derbe, cities of Lycaonia, and to the surrounding country.” This forgotten geographic fact is now known to have been correct only between 37 and 72 A.D. It is hard to explain Luke’s casual reference which was so remarkably accurate, unless we accept the fact that he had been there. Over and over again Luke shows that he knows the local situation. He talks about the market place at Philippi and the Areopagus at Athens – this was a great center of learning and religious worship. He mentions the theatre at Ephesus, and this has been excavated. He speaks of the fact that the city of Ephesus was known as “the Temple-Keeper of Diana,” and he refers to the temple itself. These are points that have been exposed to the light of archaeology.

One of the ways in which archaeology has thrown light on Luke’s record is to provide a clearer picture of the events that transpired at the Areopagus at Athens (Acts 17). “Areopagus” literally means “Mars Hill” and this itself is a correct identification of an important site in Athens. Here, continuous philosophical discussion took place, carrying on Athens’ centuries-old boast of her magnificent culture. From here the teachings of Socrates, Aristotle, and Plato had gone forth. The Greek people regarded these great national philosophers as the wisest men who ever lived. And even today their greatness is acknowledged far beyond the confines of Greece itself.

What Will This Gutter-Picker Say?

In Luke’s record in the Acts we watch as the Athenian leaders of Paul’s day come together in the general vicinity of Mars Hill which rises 370 feet above the nearby plain (Acts 17:18). By Paul’s time the term “Mars Hill” or “Areopagus” had come to refer to the meeting place at the market below the hill itself. The evidence as to the precise spot is not conclusive. These leaders are not at all happy with the new teaching this despised Jew is spreading in their city. “What will this babbler say?” they ask, and we can see their brows knit, and annoyance in their piercing dark eyes.

“Babbler” – that was the term they used, and it is one on which archaeological research has brought new light. The term was used for the hungry sparrows that would flutter down into the gutter to eat what they could of the seeds that had been swept there. The sparrows were called “babblers” – gutter-pickers. To put it a more modern idiom, these philosophers were saying of the Apostle Paul, “What will this gutter-snipe say next?”

As leaders of Greek philosophy, they could spend long tedious hours talking on the great subject of the immortality of the soul – but a physical resurrection seemed to them nonsense. Paul was teaching that his Messiah who was crucified by Pontius Pilate had risen from the dead, and that others also would rise from the dead. What nonsense it seemed!

So for once there was agreement between the Stoics, who regarded the gods as vague and impersonal, disinterested in the affairs of men, and the Epicureans who stated that man must live for his own ultimate pleasure, a pleasure which could involve something transcendent as well as in the here and now. These two leading groups forgot their differences as they came together to deal with this new doctrine. “What next will this gutter-snipe say?”

Not In Temples Made With Hands

So Paul told them that the true God did not dwell in temples made with hands, and probably he pointed to the great Parthenon, that magnificent temple in Athens over their heads, now acclaimed as one of the wonders of the ancient world. Even the great temple of Athens could not contain the almighty God.

Parthenon standing about Mars Hill in Athens

Parthenon standing about Mars Hill in Athens

But the people themselves were not sure that their gods were confined to a temple such as this, for their whole city was given over to idolatry (Acts 17:16). One famous story relates to a time of famine – a national disaster. The gods had been placated, but to no avail. The famine continued. So a flock of sheep was taken up the side of Mars Hill, and then they were released. Wherever a sheep stopped, there an altar was built.

Yes, the city was wholly given over to idolatry. No wonder the Apostle Paul said, “Men of Athens, you are very religious” – for that is how the expression “too superstitious” in the Authorized Version of the Bible is better translated. “As I passed by, “said Paul, “I beheld your devotions, and I found an altar with the inscription ‘To the Unknown God’ “ (Acts 17:22, 23).

There are references in ancient writings which make it clear there was such an altar in Athens in the time of Paul, and even today similar altars are known in other parts of the world over which Paul journeyed. On the famous Palatine Hill in Rome there was an altar “To the Unknown God or Gods.” The background to Paul’s address is clearly authentic. “Whom you ignorantly worship,” he declared, “Him I present to you.” And he told them that Jesus Christ was the One they were seeking.

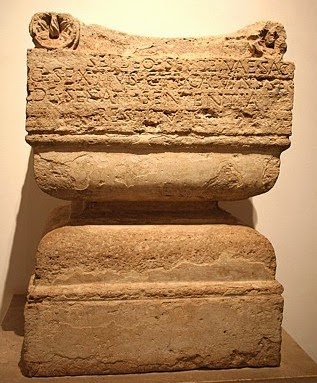

Altar dedicated to the unknown god, Rome

Altar dedicated to the unknown god, Rome

The Changing Map of Europe

Have you ever noticed how the map of Europe has altered over the last hundred years? We need only to think of the effects of two world wars to realize that Europe’s face has been changed considerably by each of those wars – and indeed at other times before and after the wars. This is not something entirely modern, for the map of Europe has been notorious for its changes throughout the centuries, as first one power and then another has become dominant against its neighbors.

These changes were going on in the first and second centuries A.D., even as they are in the 21st century A.D. Yet Luke quietly, and precisely, refers to the political provinces correctly – he talks about the regions of Phrygia, Galatia, Mysia and Bithynia in Acts 16:6-8. He talks about Syria and Cilicia, and knows that Lystra and Derbe are cities of Lycaonia, though this point recorded in Acts 14:6 would not have been accurate for every period of history.

Luke knows that the native speech at Lystra is Lycaonian, and once again this is very much the comment of an eyewitness. In that same setting at Lystra the people called Barnabas by the name of the god Jupiter, and Paul by the name of another god Mercury. This is very interesting, for Jupiter and Mercury, or Zeus and Hermes as they were known to the Greeks, were worshipped in this very area.

On Using High Titles

Perhaps one of the most thought-provoking aspects of local color is the way Luke uses the titles of various officials. He talks about the Proconsul of Cyprus (Acts 13:7), and mentions the Politarchs of Thessalonica (Acts 17:6). Luke also writes about “the chief man” (Acts 28:7), the proper title of an official on the Island of Malta.

One of the most interesting titles is that of the Magistrates of Philippi (Acts 16:20 and 35). Actually Luke gives these magistrates a higher title than, strictly speaking, they should have used. It was just as though they were calling themselves Chief Magistrates instead of Magistrates. “So,” thought the historian of a century ago, “here Luke has been caught napping.” But then, at the turn of the century, Sir William Ramsay found an inscription concerning magistrates in a neighboring colony. The inscription actually records the strange practice of these magistrates who, in their pride, took to themselves a higher title than was rightly theirs. Luke had not been caught napping, for this is just one of very many points at which Luke has been shown to be amazingly accurate.

“One Of The Very Greatest of Historians”

Many of the findings concerning Luke have resulted from the excavations of Sir William Ramsay, at one time Professor of Classical Art at Oxford University. Early in his career he wrote that he was quite opposed to the idea of Luke being an accurate historian, for he accepted the German Tubingen theory that Luke’s writings must be dated later that the first century A.D. But in his archaeological researches in Asia Minor, Professor Ramsay occasionally perused some aspects of the writings of Luke because there were areas of study where no satisfactory first-century writings had survived. Slowly, he came to realize that Luke was remarkably accurate. In fact, he says of Luke’s record in Acts, “I gradually came to find it a useful ally in some obscure and difficult investigations.” Elsewhere Sir William Ramsay says, “Luke is an historian of the first rank; not merely are his statements of fact trustworthy; he is possessed of the true historical sense; he fixes his mind on the idea and plan that rules in the evolution of history, and proportions the scale of his treatment of the importance of each incident. He seizes the important and critical events and shows their true nature at greater length, while he touches lightly or omits entirely much that was valueless for his purpose. In short, this author should be placed along with the very greatest of historians. “ (Quoted from Luke the Historian, by John A. Thompson.)

It is little wonder that Luke’s writings have been embraced by academia once again? The spade of the archaeologist has been effective in demonstrating the accuracy of one of the men whom God chose to record His revelation in Scripture. The Christian is not surprised to see this reevaluation of one of the Bible writers, for the New Testament is part of the Word of God. Did not the greatest teacher who ever lived say, “Thy Word is Truth”?