This review of biblical papers delivered at the 2008 ASOR meetings clearly shows that biblical archaeology is anything but dead, even if scholars are uncomfortable with the term itself. Indeed, it illustrates the central role that the Bible continues to play in the history and archaeology of the region; a source unmatched and unrivaled in its rich detail and description of life in antiquity...

Contemporary Issues

Commentary on recent archaeological discoveries, current issues bearing on the historical reliability of Scripture and other relevant news concerning the Bible.

- Category: Contemporary Issues

- Category: Contemporary Issues

It is inevitable...predictable...almost certain. Each year, some unbelieving scholar or entertainer seemingly comes out of nowhere with an erroneous theory that supposedly debunks the historical and bodily resurrection of the Son of God. The Da Vinci Code, the Gospel of Judas, Bloodline, The Jesus Family Tomb, liberal theologians, and even some so-called 'evangelical' scholars...on and on the list goes of those who, year after year after year, fecklessly attack the central doctrine of the Christian faith.

- Category: Contemporary Issues

To date, the Ark has not yet been found. Several locations for it have been proposed: Mount Ararat in northeastern Turkey; Mount Cudi (Judi) in southeastern Turkey; the so-called Durupinar site near Mount Ararat; and several mountains in northern Iran, including Damavand, Sabalon, and Suleiman...

- Category: Contemporary Issues

One of the most serious problems facing the Church in the 21st century is the problem of Biblical illiteracy. Simply put, most professing Christians do not possess a sound and coherent understanding of the Bible...

- Category: Contemporary Issues

Incontrovertible proof to refute Christianity?

A former graduate student of mine, Brenda, did an undergraduate degree in journalism. She recounted a statement that was made by her professor in one of her “Journalism 101” lectures. The professor said, “The two things that sell newspapers, books, and movies are sex and sensationalism!” Evangelical authors generally don’t dabble in the first (unless it’s Dr. Tim LaHaye who wrote The Act of Marriage!), but there are some who have mastered the art of the second. In evangelical circles, we are inundated by the sensationalistic archaeological claims by so-called modern day Indiana Joneses who claim to have found everything from the Ark of the Covenant with the blood of Jesus on it in Jerusalem (or in Ethiopia, minus the blood), the real tomb of Jesus on the Mount of Olives, Noah’s Ark in Iran, the real Cave of Machpelah, Pharaoh’s chariot wheels in the Red Sea, the Ten Commandments, the ashes of the red heifer, Mount Sinai in Saudi Arabia, the plan of the ages in the pyramids, the manger of Jesus, and the list goes on and on. Unfortunately for them, under close scholarly scrutiny, these claims evaporate into thin air.

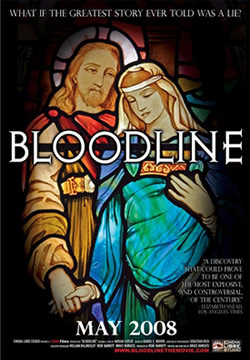

The secular world is not immune to the sensationalistic approach to archaeology either, but sometimes with a more sinister twist: to try and discredit the Person and Work of the Lord Jesus Christ. One just has to read The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown (2003); The Jesus Dynasty by James Tabor (2006); and The Jesus Family Tomb by Simcha Jacobovici and Charles Pellegrino (2007). Now there is a new movie out that makes the same attempt to attack the deity of the Lord Jesus and His bodily resurrection. It is called “Bloodline,” and produced by 1244 Films (2008). The director and narrator of the movie is Bruce Burgess and the producer is Rene Barnett.

The secular world is not immune to the sensationalistic approach to archaeology either, but sometimes with a more sinister twist: to try and discredit the Person and Work of the Lord Jesus Christ. One just has to read The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown (2003); The Jesus Dynasty by James Tabor (2006); and The Jesus Family Tomb by Simcha Jacobovici and Charles Pellegrino (2007). Now there is a new movie out that makes the same attempt to attack the deity of the Lord Jesus and His bodily resurrection. It is called “Bloodline,” and produced by 1244 Films (2008). The director and narrator of the movie is Bruce Burgess and the producer is Rene Barnett.

I went to the Jewish Museum on 5th Avenue in New York City on Monday, May 5, 2008, for the press conference of this new movie. As I entered the museum, there was a large poster on a tripod in the lobby that had a picture from a stained glass window in the Kilmore Church in Dervaig, Isle of Mull, Scotland of Jesus and Mary Magdalene holding hands (and Mary looking pregnant). Above the title of the movie was the provocative question: “What if the greatest story ever told was a lie?” I thought to myself, this is going to be a very interesting news conference, especially with the cast of characters on the panel - and they did not disappoint.

The premise of the movie is that they have “incontrovertible proof” that would “totally refute” Christianity. The movie claims that Jesus married Mary Magdalene and had a child, or children (the sex selling point). After the crucifixion of Jesus, Mary hid the body of Jesus and she and her child, or children, moved to France. The Knights Templar rediscovered the body of Jesus and brought his mummified body to Rennes-Le-Chateau, in southwest France. The movie suggests that the mummified body of Mary Magdalene was recently discovered in the area along with other 1st century AD artifacts from the Jerusalem area associated with the wedding of Jesus and Mary Magdalene (the sensationalism selling point). Another version of the story is that Jesus skipped out of Jerusalem before the crucifixion and they had “incontrovertible proof” that he was living in France in AD 45 with Mary Magdalene and children [0:38:40]. The movie isn’t clear on which scenario actually happened.

A Knights Templar “tomb” was found in 1999 by an English adventurer and treasure hunter named “Ben Hammott.” This name, however, is an alias because he is afraid that some people are out to get him. Interestingly, the Hebrew meaning of his name is “son of the death.” He is also known on the Internet as Tombman. He was intrigued by the Rennes-le-Chateau mysteries after reading Holy Blood, Holy Grail. Hammott claims that the tomb of Mary, Jesus and others, along with lots of other treasures, were found by a local priest named Berenger Sauniere at the end of the 19th century. The priest reburied them in this Templar’s tomb and then blackmailed the Vatican for a “princely sum.”

The priest allegedly left a note with his last confession in a bottle that was found by “Ben Hammott.” The priest’s confession purportedly is: “The resurrection of Jesus was a trick, it was Mary Magdalene who took his body from the tomb. The Disciples were fooled. Later, the body of Jesus was discovered by the Templars and then hidden three times. The Knights protected a great secret which I have found. Not in Jerusalem. The tomb is here. Parts of the body are safe. I have abandoned and renounced my false Church [He is referring to the Roman Catholic Church - GF]. I have done what I have done to preserve the secret. Maybe in the future the time will come for the secret to be revealed.” These are pretty serious claims that are protected by a shadowy organization called the Priory of Sion.

Where’s the Beef?

Some will recall the Wendy’s hamburger commercial that compared their large hamburgers with their competitor’s very small hamburgers and the now famous question that was asked: “Where’s the beef?” With this movie, a similar question is asked, “Where’s the evidence?” But unlike the Wendy’s commercial where the competitor had at least a small beef patty, this movie has no credible evidence for its claims!

This movie purports to be a serious documentary about the proof for the bloodline of Jesus. One should be suspicious these days when “documentaries” come along that make amazing and sensational claims.

Did Mary Magdalene Make it to France?

The movie claims that there was a “thriving Jewish community” in southwest France in the 1st century AD [0:47:34]. That would be an ideal place for Mary and her children to flee from Jerusalem after the crucifixion of Jesus. Unfortunately there is no documentation for this statement, nor are any “expert witnesses” interviewed to substantiate this claim. In fact, the opposite is true, there was no thriving Jewish community living in southwest France in the 1st century AD.

Emil Schurer, in his monumental work, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ, states: “As for Southern Gaul it is possible that Jews resided there in the earlier Imperial period, since Christian communities were established in Lyon and Vienne already in the second century, and the Christian missions, at least in the New Testament times, tended to follow in the traces of the Jews. Apart from very scattered individual items of archaeological evidence, there is however no definite attestation of a Jewish settlement in Gaul until the fifth century” (1986:III.1:85). Notice Schurer’s evidence for a possible Jewish community in the 1st century is based on speculation. The hard evidence does not point to a thriving community in the area at the time of Jesus, but rather the 5th century AD.

Other scholars addressing the archaeological evidence for Jews living in France point out that of the 245 Jewish Greek inscriptions that are scattered around the Mediterranean world, none have been discovered in France (Safrai and Stern 1976:II:1043). There was, however, one Herodian lamp found in France (1976:II:673), but that could easily have been brought back to southern Gaul by a French soldier in the Roman Legion.

At the news conference in New York, one of the reporters asked Bruce Burgess what evidence there was that Mary went to France. He replied that there was no strong, hard evidence, just 800 years of “evidence.”

The earliest legends we have of Mary Magdalene living in France are from the 12th century AD, about the time the Knights Templar returned to France with their relics. As Bishop John Spong, the retired Episcopal bishop of Newark, NJ, so keenly observed at the news conference, relics are a great way to increase tourism in small villages! When people come to venerate an object in a church, they would spend money in the village to boost the local economy. John Calvin, the great reformer, wrote a book on these relics, including the tail of the donkey Jesus rode into Jerusalem on (1854: 243). He noted that Mary Magdalene had “two bodies, one at Auxerre, and another of great celebrity, with its head detached, at St. Maximin, in Provence” (1854: 265). Apparently “Mary Magdalene” was schizophrenic and Calvin was unaware of the Rennes-le-Chateau “body”!

The Parchments and Scavenger Hunt

“Ben Hammott” discovered the cave that contained the tomb with the “corpse” of Mary Magdalene, as well as a wooden chest with the relics from Jerusalem of the 1st century AD. He did this based on clues and measurements he was able to discern in the pictures and statues in the St. Mary Magdalene Church in Rannes-le-Chateau, as well as clues found in bottles that were hidden under rocks or in caves.

On his website he describes a few of the clues but not all of them. He said he will reveal them in his soon to be released book, Lost Tomb of the Knights Templar. Rennes-le-Chateau Secrets and Discoveries. Is this an infomercial for the book?

As I watched the movie it looked like an amateurish archaeological scavenger hunt. It taxed my imagination that somebody could move a rock or go into a cave and voila, there was a bottle with a note inside. What really alarmed me was how fresh looking, flexible and clean some of those “parchments” appeared in the movie. Anybody who has done any research in libraries knows how brittle and discolored pages could be in books from the 19th century. When these books are copied there is always a concern that the pages will crack. In the movie, the “parchments” unroll too easily for paper that had been rolled up for 100 years. The paper did not look faded and should have cracked when opened so quickly, if in fact, they are 100 years old.

To add credibility to this story, the producers of the film should have a paper expert independently test the paper and ink in order to determine the age of each “parchment.” Experts in this field could examine the paper and tell the date of the paper. Chemical analysis can determine the content of the ink which could give us a date for the ink as well. Readers may recall that similar tests were done on the so-called “Hitler’s Diary” that was eventually determined to be a hoax.

There are some Rennes researchers who question the French and Latin of these parchments and suggest they were written by an Englishmen. One researcher thinks the whole movie is bogus.

The Body of Mary Magdalene

The movie, following the lead of Reverend Lionel Fanthorpe, an Anglican priest from Wales and an avid Rennes researcher, suggests that Mary Magdalene and Mary of Bethany are the same person [1:41:14] See also Fanthorpe and Fanthrope 1999: 231-238. The evidence for Mary Magdalene and Mary of Bethany being the same person is non-existent (Bock 2004:13-59; Witherington 2006:15-51).

“Ben Hammott” discovered a small entrance inside a cave that led to another cave complex in 1999. On his first visit, his video camera fell down the hole, but he was able to retrieve it. At the hotel he watched the video and saw what the camera had captured. It revealed what appeared to be a shrouded corpse with the red cross of the Knights Templar. A year later, they returned with better equipment and lights for the video camera. This time they clearly saw the shrouded object as well as other treasures in chests and boxes.

In December 2006, “Ben Hammott” went back to the cave with Bruce Burgess who brought along a “remote camera rig.” In the movie, Hammott has some kind of device (a knife? on a pole) that cuts the shroud in order to reveal the face of the corpse [1:32:58]. He then cuts the area where the hands are and exposes them. I do not know what the antiquities laws are in France, but the cutting of the shroud could be a deliberate desecration of an archaeological artifact. I am puzzled as to why they did not just lift the whole shroud off the body and expose the entire corpse without cutting the shroud. I suspect the shroud was cut to expose only two parts of the “body”, the head and the hands. The head was exposed in order to show that the corpse was a woman. The hands had a unique clasp that they associated with the clasped hands of Mary Magdalene on a picture on the altar of the church dedicated to her in Rennes-le-Chateau.

A hair sample was obtained and submitted to the Paleo-DNA Labs at Lakehead University in Canada for analysis. The mitochondrial DNA suggested “the Middle Eastern maternal origins of the individual based on haplotyping information.”

It was also noted that this individual was placed on a slab of marble as if she was being venerated [1:36:26]. The conclusion drawn by “Ben Hammott” is that this is the mummified body of Mary Magdalene [1:34:43; 1:39:23].

The body, however, could not be Mary Magdalene, or any other Jewish person, for that matter. During the Second Temple period (the time of Jesus), Jewish people never mummified their dead. At the burial of Jesus normal Jewish burial customs were followed (John 19:38-40). When a Jewish person died, they were taken to the family tomb and buried before sundown. The body was washed and perfume and spices put on it to counteract the decaying stench of the corpse once it started to decompose. The family would have a one week period of intensive mourning, called shiva. Then there was a less intense period for thirty days, called sholshim. At the end of the year, the family met at the tomb and gathered the bones of the dead individual, washed and anointed them, and placed them in a bone box called an ossuary. This funerary practice is called ossilegium, or secondary burial (Fanny 2000; Rahmani 1961; 1981; 1982a; 1982b; Zlotnick 1966).

The Jewish people during the Second Temple period practiced secondary burial and did not mummify their dead. The only known Israelites to be mummified were Jacob and Joseph (Gen. 50:2, 3, 26), and they were the exception to the rule. Who the mummified “person” is in the movie, I do not know, but it is not Mary Magdalene, nor are any of the other mummified bodies that are purported to be in the tomb those of Jewish people either, and for sure, not Jesus.

If the producers of the movie wanted a better Biblical connection with the burial of “Mary of Bethany, alias Mary Magdalene” (which I do not believe is the case), they should have looked to Jerusalem. In the early 1950’s the Franciscan archaeologists excavated a necropolis at Dominus Flavit on the Mount of Olives. In Loculi 70 an ossuary was found, designated no. 27, with inscriptions in Hebrew with the names “Martha and Mary / Miriam” three times! (Bagatti and Milik 1981:77-79; Fig. 3-5; Photo 77, 78). It is quite possible that this ossuary contained the bones of two sisters. We know from the New Testament that there were two sisters with these names from Bethany, on the back side of the Mount of Olives, that lived together (Luke 10:38, 39), one of them was named Mary of Bethany (John 12:1-3). If we follow the movies’ scenario, one could make a better case that this ossuary contained the bones of “Mary of Bethany, alias Mary Magdalene”, and not the so-called mummified remains in France. At least this burial followed the Jewish burial practice of ossilegium, or secondary burial.

The Wooden Chest with First Century Artifacts

There was a parchment in the fourth bottle found by “Ben Hammott” that indicated that a wooden chest could be found with “the parchments of Abbe Bigou, the cup of Jesus and Mary, and the anointing jar” [1:09:06]. The location of this chest was found by using “clues” from the church and parchments from the bottles. These all pointed to a place, known by the locals, as the “Burial Cave of the Magdalene.” Once they located the cave, they used a very unorthodox method to locate the exact spot of the wooden chest. The dowsing rod they used pointed them to the back of this cave [1:10:51]. When they dug down a few centimeters, voila, there was the wooded chest! (If only real archaeologists could be so lucky!).

Bruce Burgess commented that the chest was “extremely damp and rotten.” When I looked at it during the news conference in New York, it did not look rotten, although I did not handle it. The chest should be examined by experts and the kind of wood determined as well as a sample taken for carbon dating and it should be tested. The chest could easily have been purchased from an antique dealer recently somewhere in France. In the movie, when Hammott was using the petech (a tool used by archaeologists for digging dirt) or geologist hammer, he hit the wood of the chest. It gave a sound of a solid piece of wood with a hollow inside [1:11:23; 1:11:46-48], and did not give the sound of wood that was “damp and rotten.” If the wood was “damp and rotten” it would have crumbled or at least left a hole in the top of the chest made by the petech.

The parchment and the movie claim that these first century artifacts were connected with the wedding of Jesus and Mary Magdalene. Professor Gabriel Barkay of Bar Ilan University in Israel attested to the authenticity of these objects and stated that they dated to the time of Jesus (some of the coins, however, were earlier and later than this time). I personally looked at them during the New York news conference and I am sure they are authentic and were correctly identified and dated by Dr. Barkay. In the wooden chest was a ceramic cup, an ungenterium, a glass phial with a parchment rolled up inside, and about thirty coins. Can these items be associated with the wedding of Jesus?

Before this question can be answered, the issue of Jesus’ marriage should be addressed. This is an idea that has been popularized by The Da Vinci Code (2003), but it has been circulating in some theological circles (Spong 1992:187-199; Fanthorpe and Fanthorpe 1999:231-238; Starbird 1993). When the movie, The Da Vinci Code, came out, evangelical scholars responded to the ideas expressed in both the book and movie. The works of Dr. Darrell Bock (2004: 13-59) and Dr. Ben Witherington III (2004: 28-37) should be consulted. There is no Biblical evidence to support the claim that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene or anybody else, for that matter. Now let us turn our attention to the artifacts found in the wooden chest.

The first artifact in the chest was a ceramic drinking cup. In his analysis, Dr. Barkay described it as a “bowl with an out flaring rim and a flat base” [1:18:13], similar to what Paul Lapp identifies as a small deep bowl (Lapp 1961:175). In the press release it was described as “simple pottery drinking cup” Barkay stressed that it was “common,” thus an ordinary household item that was used everyday by everybody.

Reverend Lionel Fanthorpe states that Mary of Bethany is Mary Magdalene and she was very wealthy [1:41:15]. A case can be made that Mary of Bethany was wealthy, but not that she was Mary Magdalene. Jewish wedding during the Second Temple periods were elaborate and festive affairs. The bride and groom would not have used a common cup made of course pottery for their wedding festivities, but rather, one of silver, gold, glass, or Eastern terra sigillata pottery (Avigad 1980:91). Using a “common” cup, if it was a cup and not a bowl, would be like a wealthy bride and groom at a wedding today toasting each other with a Styrofoam cup!

The second artifact in the box was identified as an ungenterium. This object is used to hold unguents, or perfumes, and is used for domestic as well as funerary purposes. They were regularly left in tombs so that the perfumes could counteract the smell of the decomposing flesh. The first century ungenterium is called a piriform bottle in the archaeological literature (Kahane 1952a, 1952b; Lapp 1961: 199; Avigad 1980:127-129, photo 124; Vitto 2000: 88, 107, 111). This piriform bottle could not have been the object used by “Mary of Bethany, alias Mary Magdalene” to anoint Jesus for His burial for three reasons. First, the piriform bottle is made of clay, but the Bible says that the vessel Mary anointed Jesus with was made of alabaster (Matt. 26:7; Mark 14:3). Second, the piriform bottle is completely intact. The Bible says Mary broke it in order to anoint Jesus (Mark 14:3). Finally, the vessel is too small. The Bible says it contained a pound of spikenard, thus the vessel would have been much larger then the one found in the chest (John 12:3).

The third object in the chest was a glass phial, also called an alabastra. Inside of this glass vessel there was a rolled up parchment which was carbon dated by the University of Oxford radiocarbon accelerator unit. The results suggest that there was a 68.2% chance that it dated between AD 1440 and 1480, or a 95.4% chance that it was dated between 1450 and 1520. Unfortunately the test was done only on the parchment and not the ink. All that the test reveals is that the parchment was made about AD 1452, but does not tell us who wrote the message, when it was written and what their motives may have been for writing it. For all we know, somebody could have taken a blank corner of a parchment that was known to be old and wrote a “message” on it a couple of years ago, rolled it up and placed it in the glass alabastra that could have been recently bought on the antiquities market in Jerusalem!

The clues from the fourth bottle said they would find the “parchments (plural) of Abbe Bigou” in the chest [1:09:06]. Abbe Bigou is identified as the priest of Rennes-le-Chateau before the French Revolution. There are two unexplained discrepancies with this discovery. First, the clue from the fourth bottle said there would be parchments, plural, more then one. There was only one in the phial and none others in the wooden chest. Second, the French Revolution began in 1789. It is not stated what years before the French Revolution that Abbe Bigou was the priest. The movie needs to explain why there is a 300-odd year discrepancy between the carbon date of the parchment and the beginning of the French Revolution.

There were about 30 coins in the wooden chest and all the coins appear to have been minted in Jerusalem. This hoard of coins covered a range of about 1,400 years, including Hasmonean coins (second century BC), Herodian coins (end of first century BC), first century procurator coins, Byzantine coins (fifth, sixth century AD), one Umayyad (Islamic) coin and the latest was a Jerusalemite Crusader coin, probably of King Baldwin, of the 12th century AD. The last coin hints at the fact that the hoard was gathered by the Crusaders, most likely in the 12th century. If it was gathered the 12th century then it would be possible that the Knights Templar brought them back when they returned to France. However, it could also that they were gathered together in the 21st century. Anybody could have easily purchased them on the antiquities market in Jerusalem or even from the young boys outside of Jaffa Gate or near the Gihon Springs in Jerusalem who sell post cards and ancient coins.

Internal Inconsistencies

There are internal inconsistencies within the movie, but I will leave them to be pointed out by the Rennes researchers who know a whole lot more about the subject then I ever will.

Some have already noted objects in the “tomb” that have been moved about even though there is only one small entrance and nobody has supposedly been in the cave. Another is the incorrect spelling of the French and Latin on the parchments that were allegedly made by the well-educated priest, Berenger Sauniere. I think once the movie is released to the public, more inconsistencies will be discovered as it is scrutinized by the knowledgeable Rennes researchers.

Two inconsistencies I noticed are these. First, when the interview with Gino Sandri, the supposed general secretary of the Order of Priory of Sion, was finished, Bruce Burgess said they turned off the cameras. We see a man in the back of the café get up and hand Sandi a note before this mystery man walked out of the café [0:11:39]. The next scene we see Sandi holding the card with his thumb partially covering the note, but part of the note can be read. Burgess said, “Who he was and what the note says, I do not know.” Yet the note is shown in the movie. Is this a Hollywood reconstruction of the event for dramatic purposes? If so, is that really Gino Sandri in the movie or just an actor? At best, this movie should be called a docudrama, but not a documentary.

The second inconsistency was the discovery of the third bottle. In this “discovery,” “Ben Hammott” and somebody else are trying to remove a rock from the ground. When it is finally loosen, Hammott rolls down the hill with the rock. For a brief second, we see the ground that was underneath the rock and there is no bottle to be seen [1:00:53]. After Hammott stops his roll, the movie cuts back to the spot where the rock is, and there is the bottle [1:01:02]. The question that needs to be answered is who put the yellow or orange bottle there?

One burning question I have is who was the second person in the cave with “Ben Hammott” when he cut the shroud and exposed the head and hands of “Mary”? In the movie it is a night scene [1:27:19], Ben is spooked because he thinks somebody is out to get him. He leaves Bruce and his cameraman to watch the car while he walks to the cave alone with one flashlight and a large carrying case, presumably containing the remote camera equipment [1:29:27]. Once inside the cave, we see the lights on the floor of the cave from two flashlights [1:29:40] and the shadow of somebody using a video camera [1:30:03]. “Ben Hammott” could not have done that alone. Was there a fourth person in the party that we are not told about? Or did Bruce and the cameraman get scared of the wild boars and go in anyway?

Will the Tomb Ever be Excavated?

At the end of the movie it was announced that, “Planning is now underway for a full scale archaeological examination of the tomb site with Ben Hammott and the French government” [1:55:06].

At the press conference I asked Lionel Fanthorpe when the excavation will be conducted. He said it would depend on “Ben Hammott” because he is taking care of his cancer-stricken son. If his son does have cancer, we wish him well and pray for his recovery. However, this could be a very convenient excuse to postpone the “examination” indefinitely. I, for one, am not holding my breath waiting for a news conference from Paris, London or Hollywood about spectacular discoveries from some cave near Rennes-le-Chateau. My mind, skeptical from experience, doubts the possibility that the French antiquities authority, the DRAC-LR, has jurisdiction over a movie set in Hollywood, California, or even England!

The Agenda of Bloodline

Bishop Spong stated at the news conference that the premise of the movie was “nuts” and that the movie itself was “speculation” and “off-the-wall.” Normally I do not agree with the bishop’s theology, but I was shouting inside myself, “Amen, preach it!” (He even autographed one of his books for me after the press conference.)

At the end of the movie, Bruce Burgess said, “For the record, I do think that it’s possible that these discoveries, especially the chest and maybe even the tomb were somehow placed there for Ben and us to find. That doesn’t make them fake in any way. It just means that someone with an agenda wanted this material revealed, but who?” [1:49:53].

I can think of three possibilities. First, some secret organization who wants to disprove the deity and bodily resurrection of Jesus and will bump off anybody in the way of their agenda. Second, people who want to sell books (a la Lost Tomb of the Knights Templar) and movie tickets (a la Bloodline). There is a third, yet more driving, possibility. Bloodline has an agenda. The message they are trying to get out, disguised as a serious documentary, is that Jesus is not God and He did not come back from the dead.

Bruce Burgess, however, dropped some subtle hints that this movie might be a hoax. He said that when he saw the video of the shrouded corpse for the first time, he thought it looked like a movie set, and too good to be true [0:48:49]. When some locals wanted to show him parchments he said he knew it was a “scam,” but he wanted to see them anyway! [0:41:14]. When he asked Professor Barkay how the first century artifacts got to France, Barkay said they could have been bought on the antiquities market in Israel recently and brought to Europe, or they could have been brought to France by Knights Templar [1:20:04]. The “buying antiquities” remark was not edited out of the movie, even though it was omitted from the press release. Professor Barkay stressed that the antiquities were “common” objects. In other words, they are a “dime a dozen” and could easily have been purchased on the antiquities market in Jerusalem, or even on eBay®, for that matter.

The film asks the question: "What if the greatest story ever told was a lie?" Perhaps the question that should be asked is: “What if the premise and storyline in this movie is a lie?” What if somebody recently placed the parchments in bottles for the archaeological scavenger hunt in order to find the wooden chest? What if somebody recently bought some ancient coins, an ungenterium, a common clay cup, and a glass phial from one of the antiquities dealers in Jerusalem several years ago and places it in the wooden chest? What if somebody recently forged all those parchments? What if somebody recently recreated a plastic mummified “body” of Mary Magdalene (actually just her head and hands)? What if somebody had an agenda to attempt to disprove the deity of the Lord Jesus and His bodily resurrection? What if they wanted to lead people away from the truth of the greatest story ever told, and also try and cash in on the run away best selling fictitious novel, the Da Vinci Code? If this is the case, we have on our hands another Hollywood Hoax.

The movie began with this quote from the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas: “Do not tell lies for there is nothing hidden that will not be revealed, and there is nothing covered up that will not be uncovered” (Gospel of Thomas 6; for a more accurate translation, see Blatz 1991:1:118). We will end our critique of the movie with this passage. While this text was not inspired of the Holy Spirit, it speaks for itself!

The Conclusion of the Matter

Fortunately, the greatest story ever told is still true. The Lord Jesus, in love, left the glories of heaven, humbled Himself, veiled His glory and became a man in order to die on a cross outside of Jerusalem in order to pay for all the sins of all humanity (John 3:16; Rom. 5:8; Phil. 2:5-11; I John 2:2). Three days later, He was bodily resurrected from the dead and is now seated at the right hand of the Father. He left no physical bloodline because He never married Mary Magdalene or anyone else while living a perfect, sinless life here on earth as God manifest in human flesh. However, He does have a spiritual bloodline. Hebrews 2:10 says: “For it is fitting for Him [Jesus], for whom are all things and by whom are all things, in bringing many sons to glory, to make the captain of their salvation perfect through suffering.” Jesus’ spiritual bloodline is composed of all who have put their trust in Him and Him alone for their salvation. His spiritual children did not earn their salvation, they did not work for it, they did not join a church or be baptized, they simply trusted Jesus to forgive all their sins so He could give them His righteousness, or perfection, so they could enter a perfect Heaven and be in the presence of a holy God forever (Rom. 4:5; Phil. 3:9; Titus 3:4-7; I John 5:13).

The Apostle John wrote in the introduction to his gospel: “He came unto his own, and His own did not receive Him. But as many as received Him, to them He gave the right to become children of God, to those who believe in His name: who are born, not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man, but of God” (John 1:11-13). In one of his epistles he also wrote: “Behold what manner of love the Father has bestowed on us, that we should be called children of God! Therefore the world does not know us, because it did not know Him. Beloved, now are we children of God; and it has not yet been revealed what we shall be, but we know that when He is revealed, we shall be like Him, for we shall see Him as He is” (I John 3:1, 2). Believers in the Lord Jesus Christ are the true spiritual bloodline of Jesus, not some fictitious Merovingian line that claims to descend from Jesus and Mary Magdalene. Do not believe the lie of the movie “Bloodline,” but rather, believe the truth of the Word of God, the Bible. Your eternal destiny, Heaven or Hell, will be determined by what you believe.

Footnotes

I have placed the beginning of a quote or fact from the movie in brackets. For example, [1:07:33] means the quote begins at one hour, seven minutes and thirty-three seconds into the movie. I have the “For Screening Only” version, so the numbers may be different when the DVD is finally released. Some statements are taken from the press release and are not footnoted, but can be found on the Bloodline website. Others are from websites and they are listed in the bibliography.

Bibliography

Avigad, Nahman

1980 Discovering Jerusalem. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

Bagatti, P. B.; Milik, J. T.

1981 Gli Scavi Del “Dominus Flevit”. Part 1. Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing

Blatz, Beate

1991 The Coptic Gospel of Thomas. Pp. 110-133 in New Testament Apocrypha. Vol. 1. Edited by W. Schneemelcher. Louisville, KY: Westminster / John Knox.

Bock, Darrell

2004 Breaking the Da Vinci Code. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

Brown, Dan

2003 The Da Vinci Code. New York: Doubleday.

Calvin, John

1854 A Treatise on Relics by John Calvin. Edinburgh: Johnstone and Hunter

Fanthorpe, Lionel; and Fanthorpe, Patricia

1999 Mysteries of the Bible. Toronto, Canada: The Dundurn Group.

Jacobovici, Simcha; and Pellegrino, Charles

2007 The Jesus Family Tomb. New York: HarperCollins.

Kahane, P.

1952 Pottery Types from the Jewish Ossuary-Tombs Around Jerusalem. Israel Exploration Journal 2/2: 125-139; 2/3: 176-182.

Lapp, Paul

1961 Palestinian Ceramic Chronology. 200 B.C.-A.D. 70. New Haven: American Schools of Oriental Research.

Rahmani, Levi

1961 Jewish Rock-Cut Tombs in Jerusalem. ‘Atiqot 3: 93-120.

1981 Ancient Jerusalem’s Funerary Customs and Tombs – Part One. Biblical Archaeologist 44: 171-177.

1982a Ancient Jerusalem’s Funerary Customs and Tombs – Part Three. Biblical Archaeologist 45: 43-53.

1982b Ancient Jerusalem’s Funerary Customs and Tombs – Part Four. Biblical Archaeologist 45: 109-119.

Safrai, S., and Stern, M., eds.

1976 The Jewish People in the First Century. Vol. 2. Assen: Van Gorcum and Philadelphia: Fortress.

Schurer, Emil

1986 The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ. Vol. 3.1. Revised and edited by G. Vermes; F. Miller; and M. Goodman. Edinburgh: T & T Clark

Spong, John Shelby

1992 Born of a Woman. A Bishop Rethinks the Birth of Jesus. New York: Harper Collins.

Starbird, Margaret

1993 The Woman with the Alabaster Jar. Mary Magdalen and the Holy Grail. Rochester, VT: Bear and Company.

Tabor, James D.

2006 The Jesus Dynasty. The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Vitto, Fanny

2000 Burial Caves from the Second Temple Period in Jerusalem (Mount Scopus, Giv’at Hamivtar, Neveh Ya’aqov). ‘Atiqot 40: 65-121.

Witherington, Ben III

2004 The Gospel Code. Novel Claims About Jesus, Mary Magdalene and Da Vinci. Downers Grove, IL: Inter Varsity.

2006 What Have They Done With Jesus? San Francisco, CA: Harper San Francisco.

Zlotnick, Dov

1966 ‘The Tractate Mourning’ (Semahot). Tractate New Haven, CT and London: Yale University.

Websites

Bloodline-the movie

www.bloodlinethemovie.com

The Fiction of Bloodline

http://www.rlcresearch.com/2008/05/02/bloodline-fiction

Ben Hammott

www.benhammot.com

Critique of the So-Called Jesus Family Tomb

http://www.plymouthbrethren.org/page.php?page_id=4062

A moving video on archaeology related to the Passion Week, by Joel Kramer of Sourceflix (Off site link).

- Category: Contemporary Issues

The Ark of the Covenant is in the news again. This time it comes from a world-renowned, truly distinguished, widely published scholar who is speaking from his field of expertise. Tudor Parfitt is professor of Jewish Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London...

- Category: Contemporary Issues

Nebo who? You mean you don't remember Nebo-Sarsekim? No wonder, because if you consult your concordance, you will find that he is referred to but once in the Old Testament...

- Category: Contemporary Issues

One day a friend sent me an invitation to a church meeting and asked me if I knew anything about the subject. On the flyer was a picture of a human skeleton with crooked teeth and a rock embedded in his forehead. The title above the skull read: 'They've Found Goliath's Skull!' Needless to say, that caught my attention...