Second in a series on the Book of Revelation, this article examines the physical and historical evidence for the Aegean island of Patmos. The author draws from both ancient sources and his own exploration of the island to provide a greater understanding of the Book of Revelation.

A Misconception

A common misconception in commentaries and popular prophetic writings is that the island of Patmos, where John was exiled, was a sort of Alcatraz (Swindoll 1986:3) or St. Helene where Napoleon was exiled (Saffrey 1975:392). This is partly due to 19th-century travelers who described the island as “a barren, rocky, desolate-looking place” (Newton 1865: 223) or as “a wild and barren island” (Geil 1896: 70). Unfortunately, these 19th-century perceptions are not accurate in describing the island in John’s day.

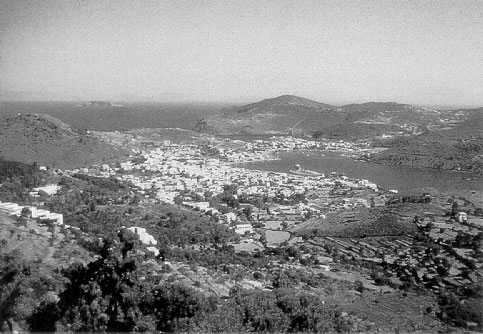

The island of Patmos (Rv 1:9). This small volcanic island sits in the Aegean Sea, 60 km (37 mi) from the Turkish coastal city of Miletus. Here the Apostle John was exiled and received his visions recorded in the Book of Revelation (sometimes called The Revelation of St. John the Divine). This view of the island is from the village of Chora to the northeast. In the center is the ancient and modern harbor, where the modern town of Skela is located. The ancient acropolis, known as Kastelli, is to the left.

First-century Patmos, with its natural protective harbor, was a strategic island on the sea lane from Ephesus to Rome. A large administrative center, outlying villages, a hippodrome (for horse racing), and at least three pagan temples made Patmos hardly an isolated and desolate place!

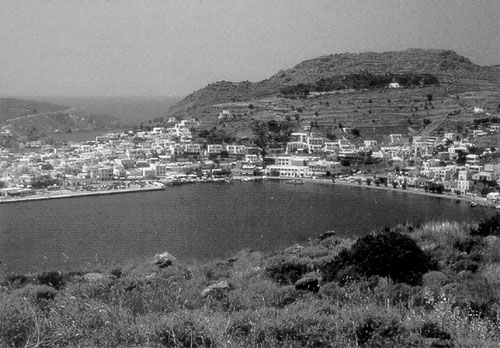

The harbor of Skela with the ancient acropolis (Kastelli) of Patmos to the right. Located on the sea lane between Rome and Ephesus,

the harbor of Patmos was a regular and important stop along the line of communication and commerce between these two cities.

Church tradition suggests John was exiled here from the city of Ephesus, where he had been serving as elder.

The 11 km (7 mi) long crescent-shaped island has a jagged 65 km (40 mi) coastline. Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79) knew the island, and in his Natural History said it was 48 km (30 mi) in circumference (Rackham 1989: 169). Central in the island and at its narrowest point is the Kastelli, the ancient administrative center. Called Skela today, it was located behind the harbor, and remains of its 1.2 m (4 ft) wide acropolis wall and three towers can still be seen (Tozar 1889: 194–95; Simpson and Lazenby 1970: 47-52). This center has a commanding view of the harbor, the sea lanes to and from Patmos and, I might add, spectacular sunsets!

Literary sources mention outlying villages on the island that probably engaged in fishing and agricultural activities. Of the three temples, one inscription mentions a temple to Artemis (Diana), the goddess of the hunt. Artemis’ main temple was in Ephesus, and known as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Patmos was probably located beneath the Monastery of St. John near the village of Chora. Threshold stones of the iconostasis (partition) in the Chapel of the Virgin may be remains of this temple.

Five courses of stone from the ancient wall surrounding the acropolis at Patmos.

From this administrative center, Roman officials had a commanding view of the harbor and sea lanes.

Literary evidence also speaks of a temple to Apollo, brother of Artemis, most likely located near the harbor of Skela. One 19th century traveler mentioned:

at the wharf I observed four or five beautiful white marble columns, cut and carved in true Greek fashion, and once very likely standing in the portico of some splendid temple to a heathen god, now used as mooring posts (Geil 1897:73).

Additional literary sources suggest the island’s third temple, dedicated to Aphrodite the goddess of love and beauty, was probably built on the Kalikatsou Rock along the Patmos shoreline.

Remains of the northeast gate of the acropolis. John probably did not live in this area, which was reserved for military

and governmental officials. Apparently free to move about the island, John probably resided in one of the outlying villages. Gordon Franz

A hippodrome on the island, known from inscription but not yet identified, was probably located near modern Skela. Using my sanctified imagination, I wonder if the Apostle John preached to the inhabitants of Patmos in this hippodrome?

Unfortunately, most tourists visiting Patmos today disembark at the port of Skela, hop a bus to the Cave of the Apocalypse, zig to the Monastery of St. John in Chora, zag to the harbor of Skela for shopping and eating before heading back to their cruise ship and out to sea. Yet, there are enough Biblically-significant sites on the island to make a serious student spend a couple of days.

Patmos has been described as a penal colony, like an ancient Alcatraz. Commentators refer to Pliny’s Natural History 4.12.69, yet it says nothing about a penal colony (Sanders 1962-63:76; Hemer 1986:221, n. 1). My impression is that John was exiled to Patmos because of its Artemis/Ephesus connections. The proconsul of Asia Minor wanted John out of Ephesus so he sent him to Patmos, also within his jurisdiction. Hemer suggests the island might be connected with Miletus, 72 km (45 mi) away (1986:28, 222, n. 8).

The length of John’s exile on Patmos differs from tradition to tradition. Most likely it lasted only 18 months, and upon Domitian’s death John was free to return to Ephesus. Dio Cassius wrote,

[Emperor] Nerva also released all who were on trial for maiestas (high treason) and restored the exile (Cary 1995:361).

Eusebius adds:

the sentences of Domitian were annulled, and the Roman Senate decreed the return of those who had been unjustly banished and the restoration of their property...the Apostle John, after his banishment to the island, took up his abode at Ephesus (Lake 1980:241).

Travels of St. John in Patmos

According to church tradition, the book Travels of St. John In Patmos was written by Prochorus (Acts 6:5), secretary to John. Critical scholarship suggests it was written in the fifth century AD. If it is historically reliable, John was only banished to the island, not imprisoned.

Travels of St. John in Patmos makes interesting reading. On the trip to Patmos, a violent storm arose and a passenger was swept into the sea. John prayed and a wave deposited the young man back on the boat. This miracle gave John opportunity to preach the Gospel. Once on Patmos, the Roman governor, Laurentius, set him free.

Kalikatsou Rock is the probable site of a temple to Aphrodite. Note nearby Aegean islands in the distance.

John makes reference to these islands (Rv 6:14, 16:20). While called "the most sacred island" of Artemis (Diana of the Ephesians, Acts 19:28), the island housed three temples-to Artemis, her brother Apollo, and Aphrodite. Aphrodite was the goddess of love and beauty.

Laurentius’s father-in-law, Myron, offers the Apostle lodging in his house, and soon Myron’s house became the first church on the island. St. John healed Apollonides, Myron’s son, who was possessed with the devil, and this miracle led to the conversion of both Chrysippe, myron’s daughter, and her husband, the Roman governor (Meinardus 1979:7).

Also recorded in Travels of St. John in Patmos is a spiritual confrontation between John and Kynops, a famous magician on the island. John was victorious and Kynops drowned in the harbor. The event is commemorated by a church today (Meinardus 1979:9). Consequently, the people of the island turned to the Lord. Before leaving Patmos, John was asked by the believers to write an account of the life of the Lord Jesus. This was the Gospel of John according to one tradition. While the historicity of these accounts is in doubt, such freedom of movement on the island is hinted at in the book of Revelation.

The Monastery of St. John above the modern town of Chora. A cave below the monastery is the traditional site of John’s visions.

What did John see?

The book of Revelation seems to reflect life on the island. Weather phenomena like white clouds (14:14), thunder and lightning (11:19; 14:2), great hail (8:7; 11:19; 16:21) and rainbows (4:3; 10:1) are common. From the peak of Mt. Elias, 269 m (883 ft) above sea level, one has a spectacular view of the Aegean Sea islands to the west and the mountains of Asia Minor (Turkey) to the east. There are at least 22 references to the “sea” in Revelation (4:6; 5:13; 7:1, 2, 3; 8:8, 9; 10:2, 5, 8; 12:12; 13:1; 14:2, 7; 15:2; 16:3; 18:17, 19, 21; 19:6; 20:13; 21:1). J.C. Fitzpatrick, visiting the island in the 1880’s, observed:

The islands to the west stand out darkly against the brightness of the horizon; and the others are lighted up with the glory of the setting sun, whilst the track of its last rays is a “sea of glass, mingled with fire” (Rv. 15:2; 1887: 16).

In Revelation 6:14 and 16:20 John describes the islands of the Aegean and the mountains of western Turkey disappearing. As of the summer of 1998, I can personally attest they are still there—awaiting future fulfillment.

Only one spring exists on the island, at Sykamia on the road from Chora to Groikos. Tradition has it John baptized some of his converts nearby. What a contrast this small spring was to the “pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding from the throne of God and of the Lamb” (22:1, NKJV) in the New Heaven and New Earth (21:1). John recognized that he was to worship the One who made heaven and earth and the sea and springs of water (Rv 14:7).

In Revelation 13:1, John wrote that he

stood on the sand of the sea. And I saw a beast rising up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns, and on his horns ten crowns, and on his heads a blasphemous name (NKJV).

A while back, a friend asked me who the beast was in this verse. I responded, “I haven’t the foggiest idea, but I can tell you on exactly which beach John stood when he saw that vision. It was the Psili Ammos beach.” The Greek text reads “fine sand” and indeed this is the only beach on the island with light, fine, golden sand and no stones or pebbles (Stone 1981: 83, 84). All the other beaches have rocks, including the Lambi beach, whose colored pebbles always impresses visitors.

The Psili Ammos beach, unique on the island for its fine sand with no rocks. The author believes

John probably stood here when he saw the vision of Revelation 13; “I stood on the sand of the sea” (Rv 13:1, KJV).

I believe John had freedom of movement on the island. He probably visited the isolated Psili Ammos beach, less than an hour’s walk from Skela harbor. Maybe he went there to get away from the noise and crowds at the harbor, or to meditate on the Word of God and pray.

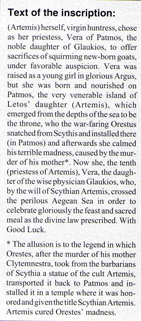

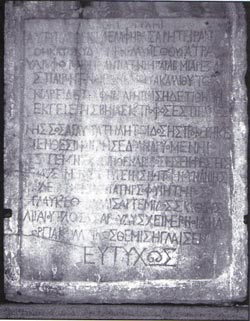

Vera, priestess of Artemis of Patmos, is the subject of this stone-carved inscription found on Patmos. Dating to the 2nd or 3rd century AD, it provides valuable information about the cult of Artemis (Diana) on Patmos. A priestess offering sacrifices suggests a temple on the island, and that Vera is the tenth priestess, suggests a long history of the cult.

Vera, priestess of Artemis of Patmos, is the subject of this stone-carved inscription found on Patmos. Dating to the 2nd or 3rd century AD, it provides valuable information about the cult of Artemis (Diana) on Patmos. A priestess offering sacrifices suggests a temple on the island, and that Vera is the tenth priestess, suggests a long history of the cult.

The Volcano at Thera (Santorini)

From this beach one could view a volcanic eruption on the island of Thera, also known as Santorini. In 1888 an interesting, but highly imaginative, article “What St. John Saw on Patmos,” by J. Theodore Bent, appeared in the journal The Nineteenth Century. He proposed that the Apostle saw a volcanic eruption of Thera (Santorini) in AD 60. This eruption of Thera possibly served as a play on words as the “beast” (Greek tharion) of Revelation 13:1. He suggested,

St. John made use of [this] phenomena which he saw with his own eyes, to prophetically depict a destruction of another kind (Bent 1888: 813).

There are several problems with this thesis. First, Bent rejects the AD 95 date for the writing of Revelation and follows the “consensus of modern opinion” (for 1888) that it was written between AD 60 and 69. Second, he assumes there was an eruption of Thera in AD 60. Unfortunately, this was based on a secondhand and probably unreliable source, George of Syngelos. In fact, it was probably confused with the well-documented AD 46/47 eruption.

History records numerous volcanic eruptions of Thera. The catastrophic eruption between 1520 and 1460 BC is suggested by some geologists as the largest eruption in historical times. It destroyed the Minoan civilization on Crete and might be the basis for the “Atlantis” legend. Strabo described another eruption of Thera in 197 BC (Jones 1988: 213, 215), while Pliny mentions one in AD 19. Several Roman historians record the AD 46/47 eruption (Vougioukalakis 1995: 13–15).

Yet, in reference to Bent’s observations, the student of Bible prophecy should not “throw the baby out with the bath water.” He compares “passages in Revelation with extracts from medieval and modern accounts given by eye-witnesses of the eruptions of Thera” and notes “many remarkable parallels" (Bent 1888: 813). Let us examine three examples.

The Sixth Seal

There was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became like blood. And the stars of heaven fell to earth, as a fig tree drops its late figs when it is shaken by a mighty wind...and every mountain and island was moved out of its place (Rv 6:12-14, NKJV).

While these events are part of a supernatural scenario in Revelation,

All these phenomena; an earthquake, a dark sun and moon like blood, “stars” falling from heaven and movement of land masses are associated with volcanic eruption. A volcanic cloud would darken the sun and make the moon appear blood red. (Bent 1888: 8:16).

Mention of late figs may even suggest a chronological indicator for when this eruption takes place, August or September (Borowski 1987: 37, 38, 115).

The First Trumpet

Revelation 8:7 describes hail and fire mingled with blood thrown to earth and destroying one third of the trees and burning up all the grass. Bent (1888:817) recounts M. Delenda’s account of the 1707 eruption where,

flames...issued out of the sea, and of the damage done to the vines and trees by the noxious vapours and by the terrible crashing of the volcanic bombs.

The Second Trumpet

And something like a great mountain burning with fire was thrown into the sea, and a third of the sea became blood; and a third of the living creatures in the sea died, and a third of the ships were destroyed (Rv 8:8-9, NKJV).

Father Richard, observing the eruption of Thera (Santorini) in 1573 wrote,

Even when the volcano is quiescent, the sea in the immediate vicinity of the cone is a brilliant orange colour, from the action of oxide iron (Bent 1888: 817).

After the 1707 eruption, Delenda observed that the sulphurous vapors mixed with the sea, turning it white and causing the fish of the harbor to die (Bent 1888: 817).

Destruction of one-third of the ships could be caused by a tsunami (tidal wave). Geologists calculated the tsunami after Thera’s 1520-1460 BC eruption as almost 43 m (140 ft) high (Pararas-Carayannis 1992: 122). That would surely wreak havoc on any navies in the area!

Earthquakes

Stothers and Rampino (1983: 6357-71) did a detailed study of volcanic eruptions in the Meditteranean Sea before AD 630 from written and archaeological sources. Earthquakes are always associated with volcanic eruption. The book of Revelation records at least five earthquakes:

1) during the sixth seal, called a “great earthquake” (6:12)

2) during the seventh seal (8:5)

3) after the resurrection of the two witnesses, called a “great earthquake” when 7,000 men were killed (11:13)

4) during the seventh trumpet (11:19)

5) the final one, during the seventh bowl judgment, described as “a great earthquake, such a mighty and great earthquake as had not occurred since men were on the earth” (16:18; NKJV).

This last statement may have reminded ancient readers in Asia Minor of stories they heard about the great earthquake of AD 17. Pliny the Elder, who ironically died studying the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in AD 79, wrote of the AD 17 earthquake:

The greatest earthquake in human memory occurred when Tiberius Caesar was emperor, 12 Asiatic cities being overthrown in night (Rachham 1979:331).

Tacitus, Roman historian and contemporary of John, described horrors of the AD 17 earthquake in vivid and graphic language (Moore and Jackson 1992: 459). John, writing less than 20 years after Pliny, speaks to his readers of a greater earthquake yet to come. A careful reading of Revelation seems to indicate these earthquakes are God’s direct intervention in judgment on humanity.

Professionals today suggest there has actually been a decline in the number of earthquakes. A bulletin, put out by the National Earthquake Information Center of the US Geological Survey, asks “Are earthquakes really on the increase?” Then they respond:

Although it may seem that we are having more earthquakes, earthquakes of magnitude 7.0 or greater have remained fairly constant throughout this century and, according to our records, have actually seemed to decrease in recent years.

They go on to point out:

A partial explanation may lie in the fact that in the last 20 years, we have definitely had an increase in the number of earthquakes we have been able to locate each year. This is because of the tremendous increase in the number of seismograph stations in the world and the many improvements in global communications (Zirbes 1999).

This should not surprise the student of Bible prophecy because no verse in the Bible says there will be an increase in the number of earthquakes before the Lord Jesus Christ returns (Austin and Strauss 1999).

The seal, trumpet and bowl judgments in Revelation need more study. All are natural phenomena on a supernatural scale, with the Lord directly intervening in the affairs of human history. These are not humanly-contrived events, be they MX missiles or black helicopters. Nations can warn and defend against missile attacks, yet natural phenomena like volcanoes, earthquakes and weather patterns can neither be predicted nor prevented by scientists. Having no control over them, they either turn to the Lord or cry out in blasphemy toward God (Rv 16:21).

| This article was first published in the Fall 1999 issue of Bible and Spade. |  |

Bibliography

Austin, S., and Strauss, M. 1999 Are Earthquakes Signs of the End Times? A Geological and Biblical Response to an Urban Legend. Christian Research Journal 21.4: 30–39.

Bent, J. 1888 What St. John Saw on Patmos. The Nineteenth Century 24: 813–21.

Borowski, O. 1987 Agriculture in Iron Age Israel. Winona Lake IN: Eisenbrauns.

Burnis, T. 1962 The Unhewn Grotto of the Apocalypse. Athens: Heraklis.

Cary, E. (trans.) 1995 Dio Cassius: Roman History, Epitome of Book LXI-LXX (Loeb). Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

Clark, F. 1914 The Holy Land of Asia Minor. New York: Charles Scribner’s Son.

Fitzpatrick, J. 1887 A Visit to Patmos. Christ’s College Magazine 15–20.

Geil, W. 1896 The Isle That is Called Patmos. Philadelphia: A. J. Rowland.

Heath, M. nd Patmos, The Sacred Island Where St. John Wrote the Apocalypse. Athens: D. G. Davaris.

Hemer, C. 1986 The Letters to the Seven Churches of Asia in Their Local Setting. Sheffield: JSOT.

Jones, H. (Trans.) 1988 The Geography of Strabo, vol. 1 (Loeb), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Kourtara, V.; Xeroutsikou, L.; and Provatakis, T. 1996 Patmos: The Holy Island of the Aegean. Athens: Toubis.

Lake, K. (trans.) 1980 Eusebius: The Ecclesiastical History, vol. 1 (Loeb). Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

Meinardus, O. 1979 St. John of Patmos and the Seven Churches of the Apocalypse. Athens: Lycabettus.

Moore, C., and Jackson, J. (trans.) 1992 The Annals of Tacitus (Loeb). Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

Newton, C. T. 1865 Travels and Discoveries in the Levant. London: Day.

Pararas-Carayannis, G. 1992 The Tsunami Generated from the Eruption of the Volcano of Santorini in the Bronze Age. Natural Hazards 5: 115–23.

Rackham, H. (trans.) 1979 Pliny’s Natural History, vol. 1. (Loeb). Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

Rackham, H. (trans.) 1989 Pliny’s Natural History, vol. 2. (Loeb). Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

Radice, B. (trans.) 1969 Pliny’s Letters, Book VIII-X, Panegyricus (Loeb). Cambridge MA: Harvard University.

Saffrey, H. 1975 Relire L’Apocalypse A Patmos. Revue Biblique 82:385–417.

Sanders, J. N. 1962–63 St John on Patmos. New Testament Studies 9: 75–85.

Simpson, R., and Lazenby, J. 1970 Notes from the Dodecanese II. Annual of the British School at Athens 65: 47–77.

Stanley, A. P. 1863 Sermons Preached Before His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, During His Tour in the East in the Spring of 1862, With Notices of Some of the Localities Visited. London: John Murray.

Stone, T. 1980 Patmos. Athens: Lycabettus.

Strothers, R., and Rampino, M. 1983 Volcanic Eruptions in the Mediterranean Before A.D. 630 From Written and Archaeological Sources. Journal of Geophysical Research 88: 6357–71.

Swindoll, C. 1986 Letters to Churches Then and Now. Fullerton CA: Insight for Living.

Tozer, H. 1889 The Islands of the Aegean. Oxford: Clarendon.

Vougioukalakis, G. 1995 Santorini “The Volcano.” Santorini: Institute for the Study and Monitoring Of the Santorini Volcano.

Wilson, J. 1847 The Land of the Bible Visited and Described. Edinburgh: William Whyte.